Back to the Beginning

The euro–dollar exchange rate has returned to its 1999 debut level as Trump’s policies unsettle markets and reopen questions about the balance of power between the two currencies. A commentary by Ignazio Angeloni

Foreign exchange markets have delivered a striking data point: the euro now trades at $1.17, exactly the same level as on January 4th, 1999 — the first day of the single currency’s existence. As if nothing had happened in between: not the twin financial crises on both sides of the Atlantic, not the digital revolution, let alone Covid, the crisis of globalisation, wars, or Donald Trump and his tariffs.

Are currency markets blind to reality — or is this merely coincidence, a chance equilibrium among opposing forces? Either way, it is a moment that invites reflection on the deeper forces driving this return to the origin.

The exchange rate, of course, has been anything but stable over these 27 years (Figure 1). The two years following the “changeover night” of January 1999 were dominated by fears that the untested euro would not withstand market pressures.

Uncertainty drove the euro down to just $0.85 in 2000. But the newcomer recovered quickly. The European economy was expanding, monetary stability was taking root, and the ECB was gaining credibility. On the eve of the financial crisis, one needed almost $1.60 to buy a euro.

After the crisis, the picture changed. The era of the strong dollar began, and by 2023 the US currency had climbed back above parity with the euro. With fluctuations along the way, that phase persisted until the arrival of the current occupant of the White House — who, without quite saying so, has declared war on a strong dollar. As recently as December, the euro traded at $1.04. Now it stands at $1.17, and no one can tell where it will go next, though the usual “experts” insist the trend will continue.

What explains these movements — and this apparent return to the starting line? Economists, who occasionally get things right, point to three broad factors.

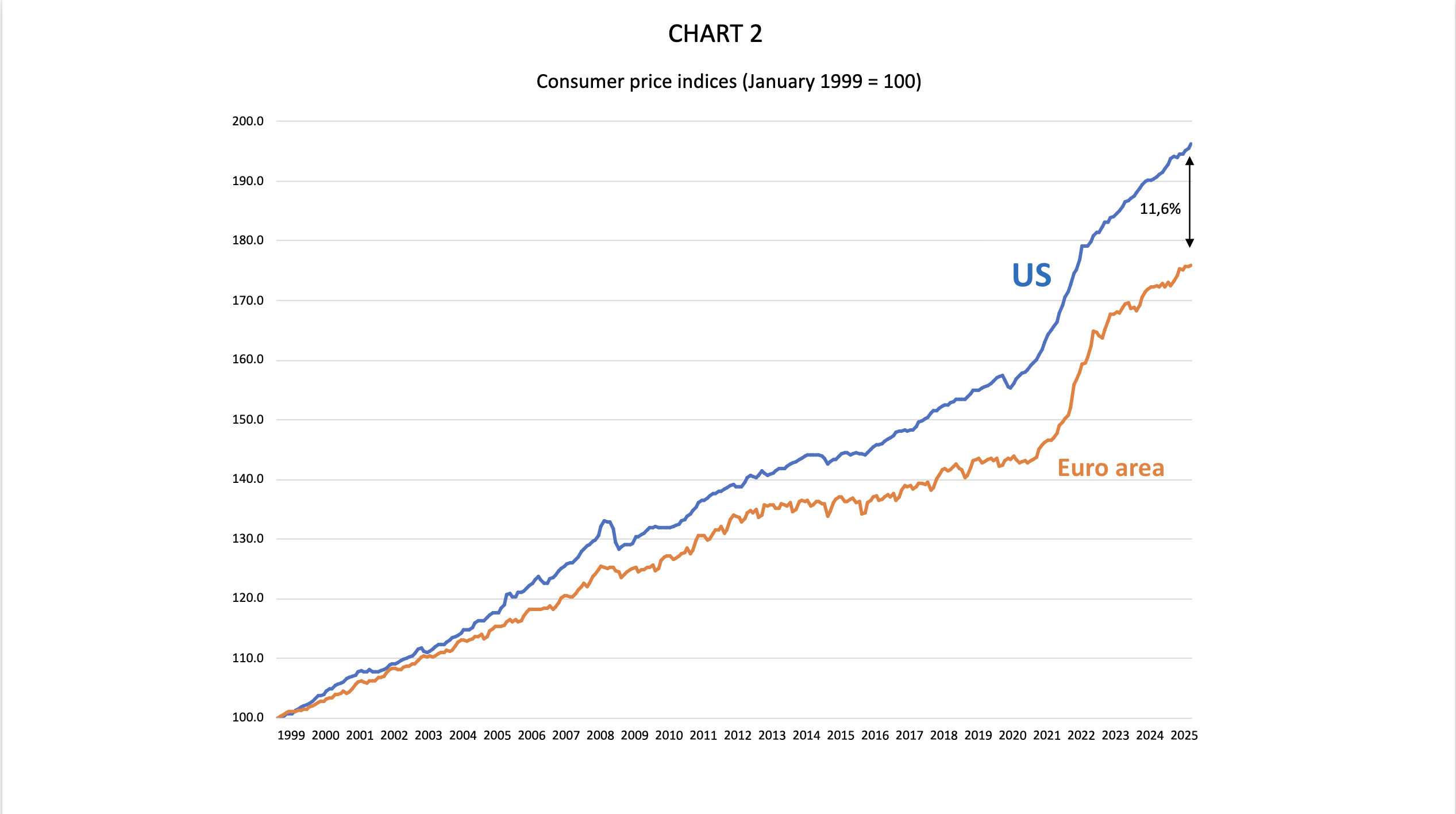

The first is inflation: a currency that loses value domestically will eventually lose value externally too. Since 1999, US inflation has been consistently higher than Europe’s. Consumer prices now diverge by 11.6% compared with January 1999 (Figure 2).

If purchasing-power parity were the only factor, the euro should today be worth $1.30, not $1.17. But there are two other drivers.

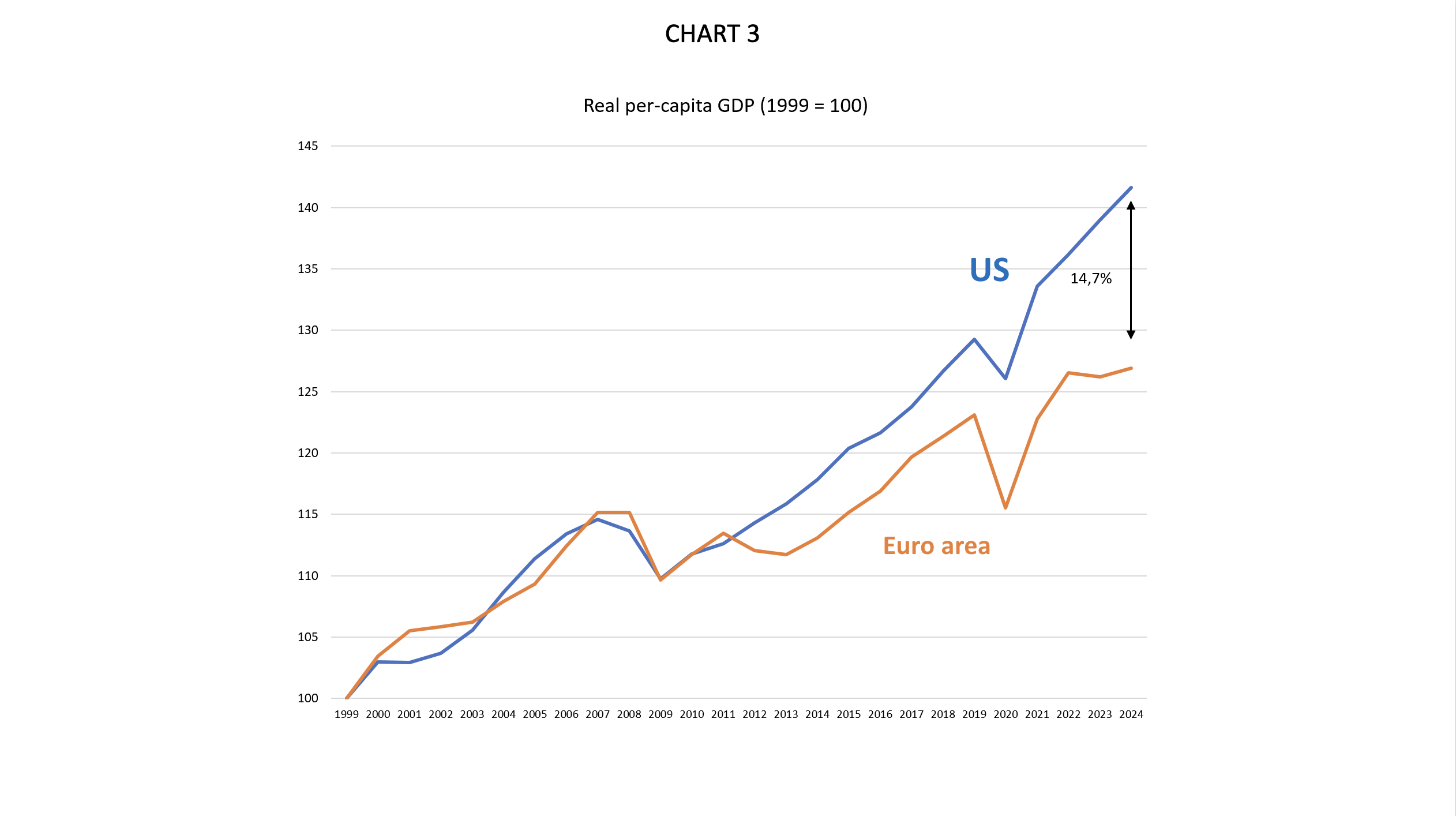

The second — perhaps the most important — is the strength of the underlying economy. An economy that grows, innovates and invests, that creates jobs and attracts capital, tends to sustain a stronger currency. On this front, the verdict favours the United States — but only since the crisis (Figure 3).

In its first decade, the euro area kept pace in terms of real per capita income. The gap widened sharply after the sovereign debt crisis. Today the accumulated divergence between the two economies stands at 14.7%. It is no coincidence that the dollar’s comeback began at precisely that moment.

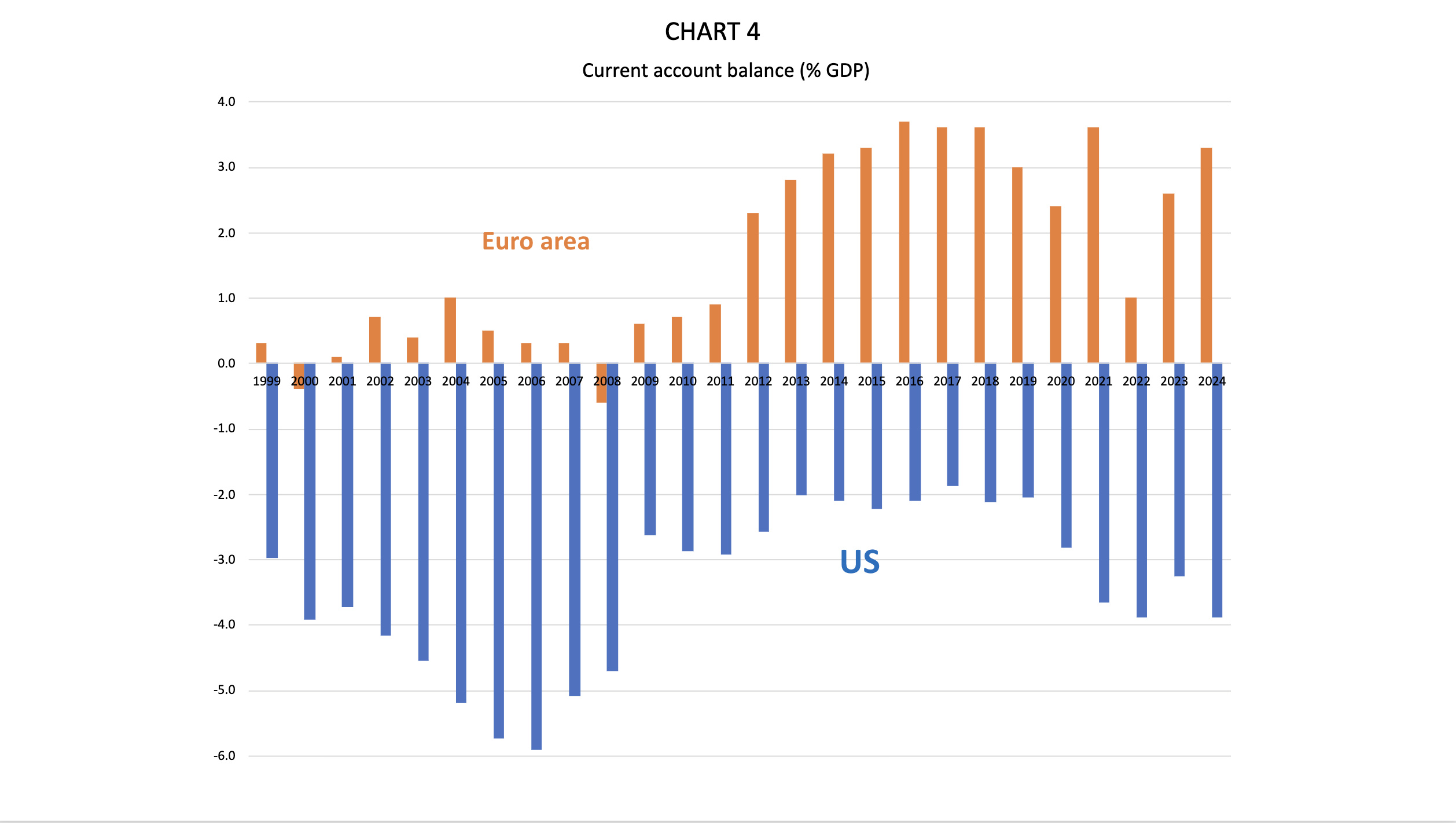

The third factor is external balance. A country running persistent current account deficits will tend to see its currency weaken, as imbalances correct and external payments are converted into foreign currencies. The United States’ chronic current account deficit has widened since the crisis, in contrast to the euro area, which moved from rough balance to a sizable surplus (Figure 4).

These elements are interconnected. The United States and the euro area reacted very differently to the crises. Structurally the two economies differ, but the key lies in policy responses.

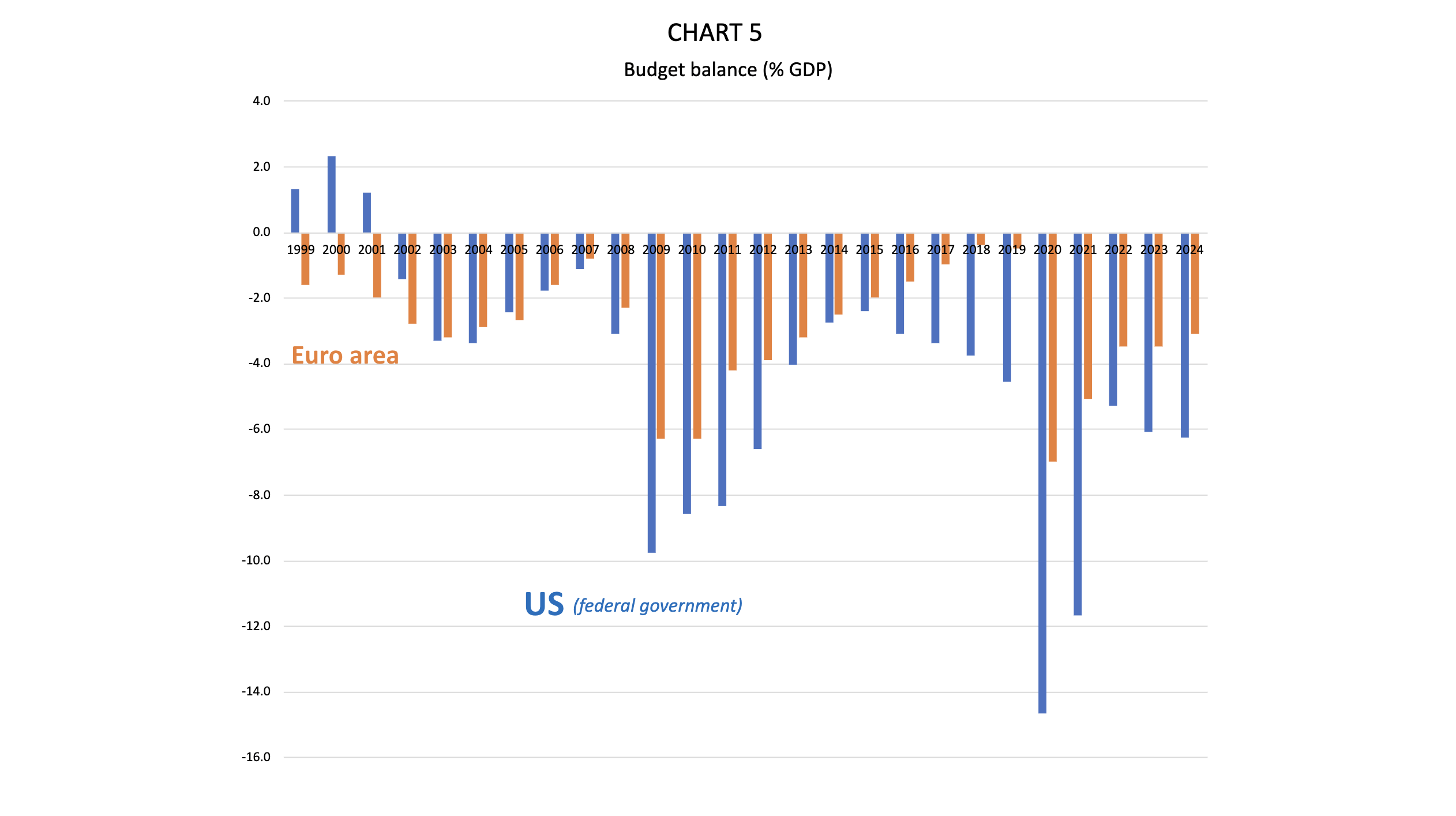

In the US, fiscal policy became far more expansionary after both crises — the financial one and the pandemic — and reacted much faster (Figure 5).

America’s ability to deploy fiscal stimulus rests on a large and flexible federal budget. The euro area’s fragmented national budgets, with varying constraints — especially in countries such as Italy, where high public debt limits room for manoeuvre — make fiscal policy far less effective.

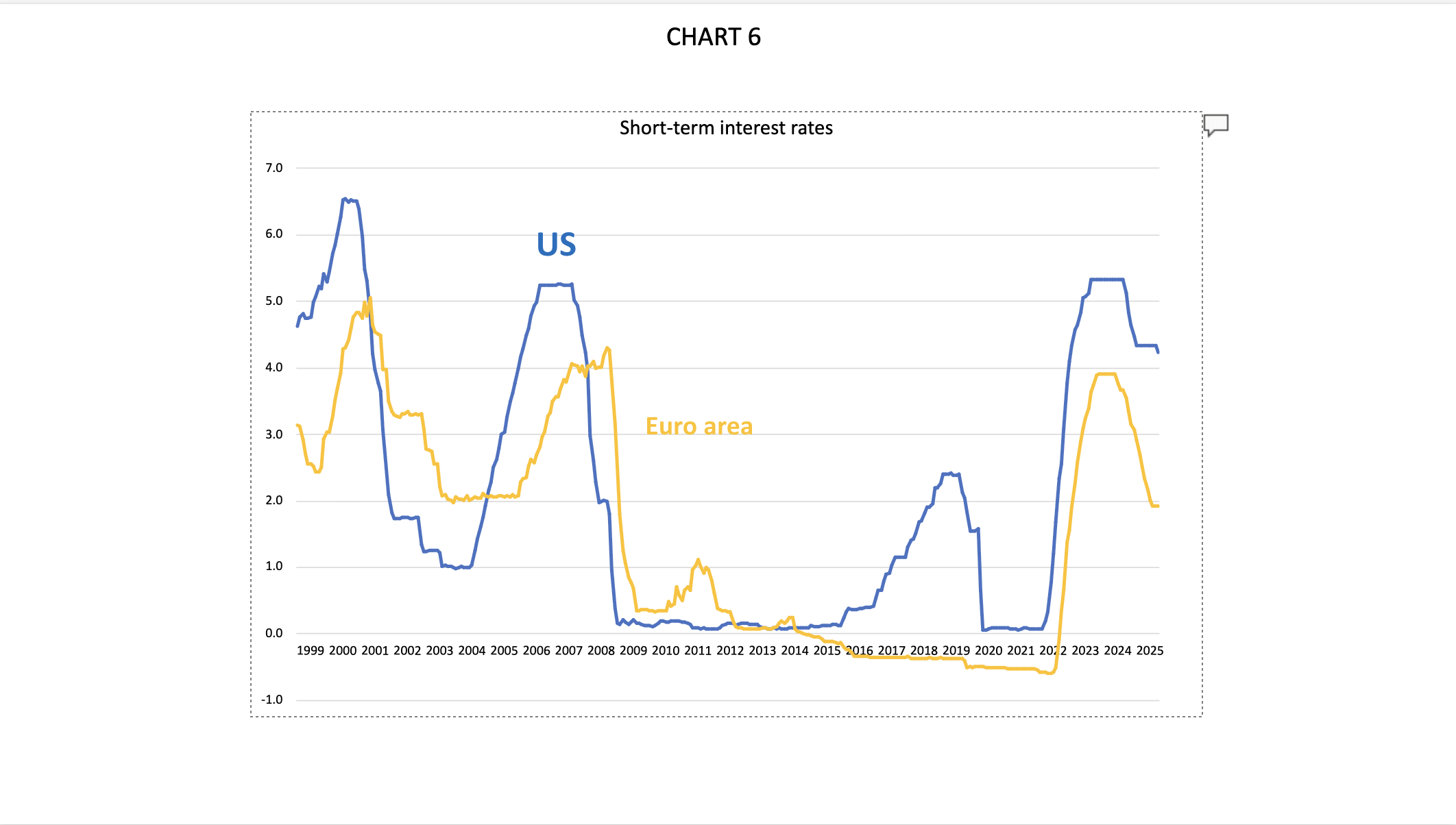

The ECB partly compensated through monetary policy. Between the financial crisis and Covid, the central bank diverged sharply, and unprecedentedly, from the Federal Reserve. Interest rates fell below zero while US rates rose (Figure 6).

In theory, tight fiscal policy combined with ultra-loose monetary policy should have spurred private investment. In practice, the formula only partly worked. Europe’s slower response mechanisms — and the unintended effects of negative rates, maintained for years — limited its impact.

The euro’s “return to origins” thus reflects a mix of factors, but not a random one. In the early years, Europe’s focus on fiscal and monetary stability helped the new currency build credibility. Later, difficulties on both fronts weakened crisis responses and reduced their effectiveness.

The subsequent weakening of the euro would likely have continued beyond 2024, had it not been for Trump’s black swan moment, which has dragged down the dollar.

If someone had told us back then that the euro would retain its value in dollars 27 years later, we would have gladly signed on. But today, the world has changed — and the future is more open than ever.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.