Be Careful What You Wish For: Germany’s New Fiscal Course Sends Ripples Through Europe

Berlin’s pledge to do “whatever it takes” on military and infrastructure spending raises government bond yields across the continent. A commentary by Ignazio Angeloni

“Be careful what you wish for, because it might just come true,” goes a popular proverb in every language. For years, Italian (and not only Italian) economic commentators have criticized successive German governments for their fiscal conservatism, urging them to loosen the purse strings.

They have denounced the constitutional rule that still—though perhaps not for much longer—limits Germany’s structural public deficit to 0.35% of GDP. By many accounts, that rule makes little economic sense.

Only now, however, that Chancellor-in-waiting Friedrich Merz has announced his intention to remove that constraint, are we realizing the consequences of a less frugal Germany. And they are not all pleasant.

All it took was last week’s announcement by the future German head of government—promising to do “whatever it takes” (borrowing Mario Draghi’s famous phrase for added emphasis) to finance military and infrastructure expenditure—for long-term German bond yields to rise by almost half a percentage point. Yields in nearly all other European countries, including Italy, followed suit.

How financial markets will adapt to a not-yet-certain scenario in which Germany starts running substantial fiscal deficits remains to be seen. Even so, three observations are already relevant for Italy.

The first is that we must reckon with a significant increase in the interest bill on Italian public debt. The simplest calculation—half a percentage point more on all outstanding debt—would point to an additional annual cost of around €15 billion, or roughly a quarter of the deficit forecast for this year.

This is a large sum, although in reality it is a high-end estimate because the pass-through of higher rates occurs gradually. An exact figure is difficult to gauge reliably; the only certainty is that this burden will materialize and will grow over time.

The second observation offers some good news for Italy: recent developments confirm a reduction in Italian public debt’s vulnerability.

Traditionally, that vulnerability manifested itself in the tendency of Italian bond spreads to widen whenever international interest rates rose—Italian yields would rise faster and higher than others.

Lately, this no longer seems to be the case. Ten-year BTP yields reacted roughly in line with their German counterparts after Merz’s announcement, leaving the spread unchanged. In fact, the spread has since narrowed further, reaching levels close to the record lows observed in 2015 (under Prime Minister Renzi) and 2021 (under Prime Minister Draghi).

Undoubtedly, markets are pricing in a less “austere” German fiscal stance—hence more akin to Italy’s—and an overall European environment far more accommodating of deficits and public debt than in the past.

Yet credit is also due to the careful management of public finances in Italy, for which the Italian government deserves recognition. The latest data show that the public deficit is decreasing, moving closer—sooner than expected—to the 3% of GDP target.

The third observation concerns interest rate prospects and implications for monetary policy. Over the past three years, evidence has been building that the decades-long secular decline in interest rates, noted by economists, has come to a halt—or even reversed—owing to several global factors: the slowdown in globalization, the return of inflation, and the greater need for both public and private investment in areas such as the energy transition and defense.

The shock emanating from Germany is simply another manifestation of these dynamics. This also affects monetary policy prospects. With its latest cut, the ECB brought its policy rate to 2.5%, which now sits below long-term yields.

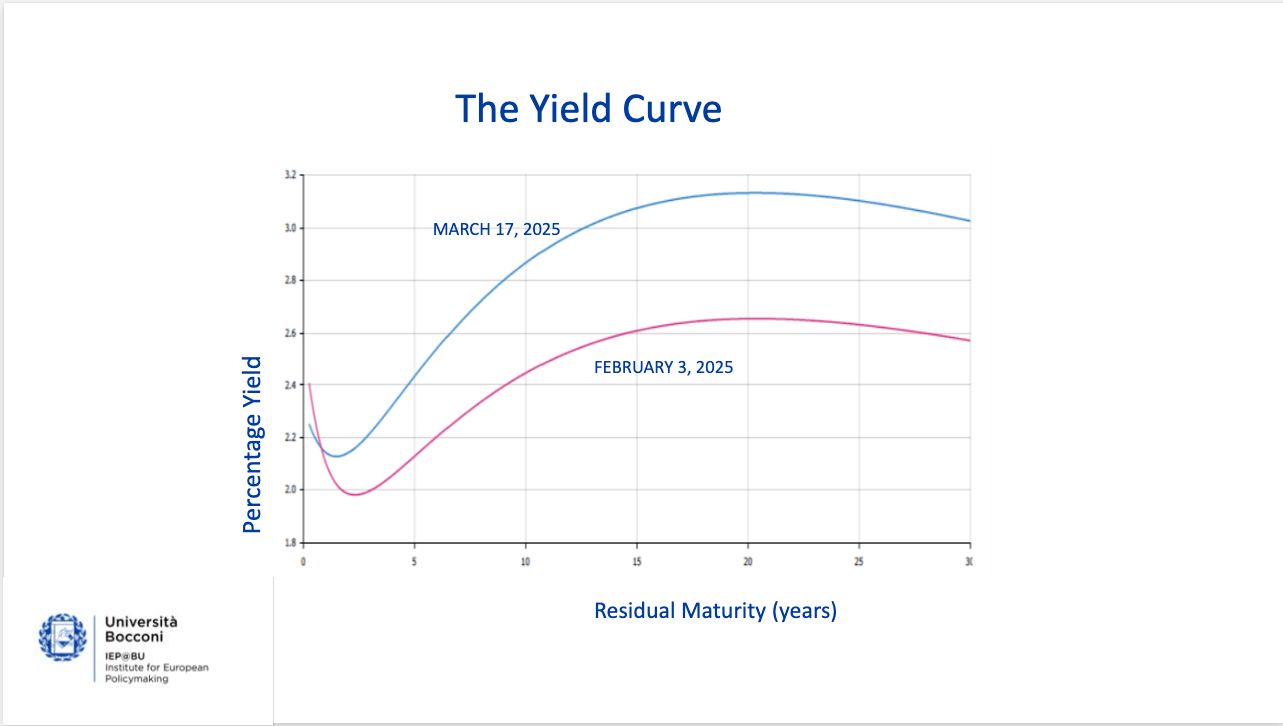

The euro yield curve today slopes decidedly upwards and, the slope has shifted substantially between early February and this week.

The steeper the curve, the more accommodative monetary policy appears relative to what markets believe will be its equilibrium level in the future. It is yet another signal to the ECB that, whatever path it has taken so far, there is little scope for further rate cuts.

An Italian version of this article was published in the daily Il Sole 24 Ore

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.