"Data Protection, Innovation, and Ethical Standards: All Digital Regulation Should be Considered Together"

Interview with Dagmar M. Schuller, CEO and Co-Founder of audEERING, on the findings of the joint IEP@BU–EconPol/ifo report on European innovation policy. By Stefano Feltri.

On the occasion of the presentation of the new joint report by the Institute for European Policymaking at Bocconi University and EconPol/ifo Institute, Prof. Dagmar M. Schuller was invited to offer her perspective on the future of EU innovation policy.

Prof. Schuller is CEO and Co-Founder of audEERING, a pioneering AI spin-off from the Technical University of Munich specializing in real-time speech analysis and voice biomarkers, whose technologies are already widely used in healthcare, market research, and automotive sectors.

Recognized as a leading expert in artificial intelligence and digital transformation, Schuller also serves as Vice President of the Chamber of Industry and Commerce for Munich and Upper Bavaria, and is a key advisor on innovation policy, technology transfer, and AI ethics.

This interview comes at a pivotal moment for audEERING, following its recent acquisition by Agile Robots, the first “unicorn” in intelligent robotics with headquarters in Munich and Beijing.

Backed by investors such as SoftBank, Sequoia China, and Hillhouse, Agile Robots stands at the cutting edge of global robotics, combining advanced AI with force-controlled robots, precision assembly, and medical systems.

With over 2,300 employees worldwide and more than 10,000 robotics solutions deployed, Agile Robots is recognized for bridging artificial intelligence and robotics innovation—expanding automation across manufacturing, healthcare, and even space.

The integration of audEERING’s expertise in voice and acoustic analysis opens new frontiers in human-robot interaction and further strengthens Europe’s position in advanced AI-driven automation.

The IEP@BU-EconPol/ifo Institute report Funding Ideas, not Companies discussed at the event, offers an assessment of why Europe continues to lag behind the US in high-tech innovation and digital competitiveness.

Despite over €100 billion spent on innovation in the last decade—much of it channeled into large collaborative projects—the impact on Europe’s ability to catch up in software and advanced technology remains limited.

The analysis finds that smaller, more flexible funding instruments—especially those directed at single recipients and SMEs—deliver the strongest and most lasting results, while large-scale, top-down collaborations too often stifle genuine innovation.

We spoke with Prof. Schuller to hear her perspective as an entrepreneur, executive, and policy advisor on what Europe needs to change to close the competitiveness gap and fully unlock its innovation potential.

Let’s start from the beginning: can you explain what your company does and how you came to found it?

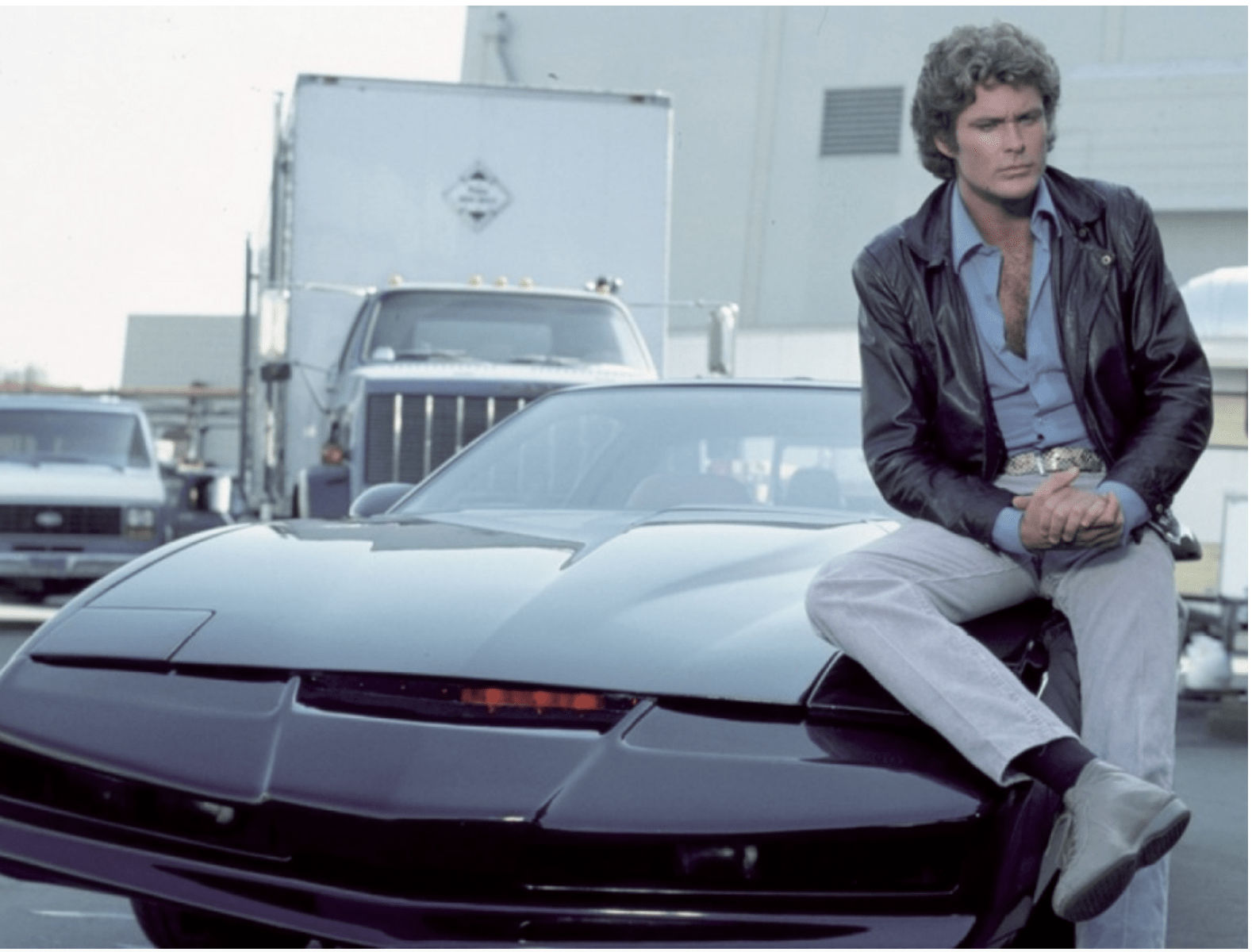

My company is called audEERING, a name that combines “audio” and “engineering.” Our mission has always been to promote well-being through advanced technology that can be scaled up. The initial spark actually came from a TV series from the 1980s—Knight Rider—which featured a smart car able not just to understand the driver’s words, but also to interpret how they were spoken.

That concept is at the heart of what we do: using “voice biomarkers.” Essentially, we extract information from the way you speak, thanks to the complexity of the human speech system—which involves dozens of muscles, from the tongue to the cheeks to the chest. If any of these muscles aren’t working properly, it shows in your voice.

Cognitive functions and physiological states also affect speech—if you’re stressed, ill, or suffering from a neurocognitive disease, this changes how you sound. Even having a fever can be detected in your vocal signal.

By analyzing speech, we can identify anomalies or dysfunctions, but also capture psychological and emotional states. Using multidimensional psychological models—like arousal and valence—we can map out how someone feels in real time.

These voice biomarkers are now utilized across various tech industries, making devices more empathetic, enhancing bots and online services, and improving human-machine communication.

How advanced is this technology? Are you already marketing products, or are you still in a research phase?

The fundamental research at TU Munich began about twenty years ago, initially focusing on speech recognition. Now we talk about “intelligent speech analysis,” which is a mature technology, on par with human capabilities in many areas, and in some cases can even surpass them.

For example, imagine a market research bot. It can not only record that a person answers “yes” to a question, but also how convincingly they say it. Three people might all say “yes,” but one is confident, one is hesitant, and one is ironic.

The underlying technology captures those subtleties, enabling more precise assessments—useful in market research, call centers, automotive systems, and particularly in healthcare.

In the well-being and medical sectors, we’re already using this technology for monitoring and screening relevant diseases—neurodegenerative, cognitive, and psychological conditions. It’s also helpful for patient monitoring and evaluating the impact of interventions. The applications are wide-ranging, and the tech is ready for the market.

Let’s talk about regulation. How challenging was it to develop this technology in Europe? Did you face obstacles that pushed you to work with the US or move your business?

We’re still based in Europe, but most of our initial clients were abroad. That’s partly because of regulatory challenges, especially data protection. In Germany, for example, data protection is fragmented, with different authorities for each region, and GDPR adds another layer. This made operating in Europe complex and sometimes discouraging.

But honestly, the bigger challenge was the novelty of our technology. When you’re the first to do something, people tend to be skeptical, assuming that if it hasn’t been done, it can’t be done or can’t be good.

Disruptive technologies are rarely perfect at first, and that puts people off in Europe, where there’s a strong expectation for perfection from the start. By contrast, in the US and Asia, companies were enthusiastic, eager to experiment and collaborate even with early-stage tech. That open attitude resulted in most of our first customers being non-European.

You mentioned data protection and mindset, but what about regulation more broadly? And funding—was that also a challenge?

When we started in 2012, there was no AI regulation on the horizon. That gave us freedom at first, since no one saw us as a risk to be regulated. But as soon as disruptive technology begins to show its potential, the regulatory environment shifts, focusing more on risks and prevention than on enabling innovation. In Europe, regulation tends to be risk-averse rather than incentive-driven.

Still, regulation can be positive if it motivates high standards in quality and ethics. Ideally, it should reward companies that demonstrate reliability and moral responsibility, rather than only penalizing non-compliance.

Is the AI Act already affecting your business or strategic decisions?

Yes, it has an impact, but we anticipated it early. As soon as we saw the first regulatory drafts, we started adapting our development and product strategies to minimize regulatory risk.

With GDPR, for example, we created a fingerprinting technology that lets us analyze data in real time without storing it, and we built in anonymization from the start. Our approach has always been to find solutions within regulatory constraints, rather than wait for problems.

That said, AI ultimately relies on data. If access to data is too limited, or data quality is too low, the technology suffers. All digital regulation should be considered together: data protection, innovation, and ethical standards are interconnected. If I don’t have enough good data, I risk bias in my models. And for AI, small datasets are practically useless—you need scale.

Earlier, you mentioned funding. I was surprised when, during the report presentation, you said you advise your team not to apply for certain SME funds. Why is that? What are the main challenges with these innovation funds?

I recommend not applying for “single-targeted” funding, especially in Germany, for several reasons. First, liquidity: as an SME, you’re not eligible to receive the money upfront, so you have to pre-finance everything. If you already have that kind of cash flow, you don’t need the grant in the first place!

Second, the administrative workload: these programs require detailed reporting and precise financial tracking, often down to individual hours per team member.

Small companies rarely have that administrative capacity, and even external accountants aren’t usually familiar with these requirements. Consortium grants are even more complicated, requiring legal advisors, project management expertise, and extensive coordination.

While these programs can be valuable for building networks and learning new processes, they rarely translate directly into standardized products or scalable innovations—something that should be improved in the European funding ecosystem.

You also said European venture capitalists often do not have the right approach to support startups like yours. What do you mean by that?

Not all European VCs are the same—some are excellent—but the majority are risk-averse and focus on incremental, “mid-tech” projects they’re familiar with. They’re hesitant about truly disruptive innovations and tend to avoid founders who “think big.” If you present your company as a potential global leader, that can be seen as a red flag in Europe, whereas in the US or Asia, it’s often expected.

Many European VCs look for reasons something might not work, rather than seeing how they could support founders to overcome weaknesses.

In places like the US or Israel, investors are much more interested in large-scale impact and are used to backing ambitious ideas, often with funding originating from defense or public sources. To be globally competitive, European investors need to embrace this mindset shift.

Why do you think this mindset persists among European investors? Is it competition, lack of funding, or something else?

I don’t think it’s about a lack of funding—Europe has plenty of money available for innovation. The issue is more about how that money is allocated and the mentality behind investment decisions.

Some VCs are open to early-stage risk and focus on the people and passion driving a company, but most are still hesitant to embrace real novelty. To build the next world leaders, we need investors who are excited by disruption and want to support, not just scrutinize, founders.

My company is called audEERING: The initial spark came from a TV series from the 1980s which featured a smart car able not just to understand the driver’s words, but also to interpret how they were spoken

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.