The EU Must Respond Smartly to Trump's Tariff Threats

A firm but measured response, aligned with rules and European interests, is better than excessive conciliation with the US administration. Here's why. A commentary by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi

How should Europe respond to the tariff war declared by the Trump administration through announcements, threats, and occasional concrete measures?

Europe faces a clear choice: either engage in negotiations only after retaliating blow-for-blow—as Canada has done—or adopt a more conciliatory tone to minimize damage. Several arguments have been presented in favor of the latter.

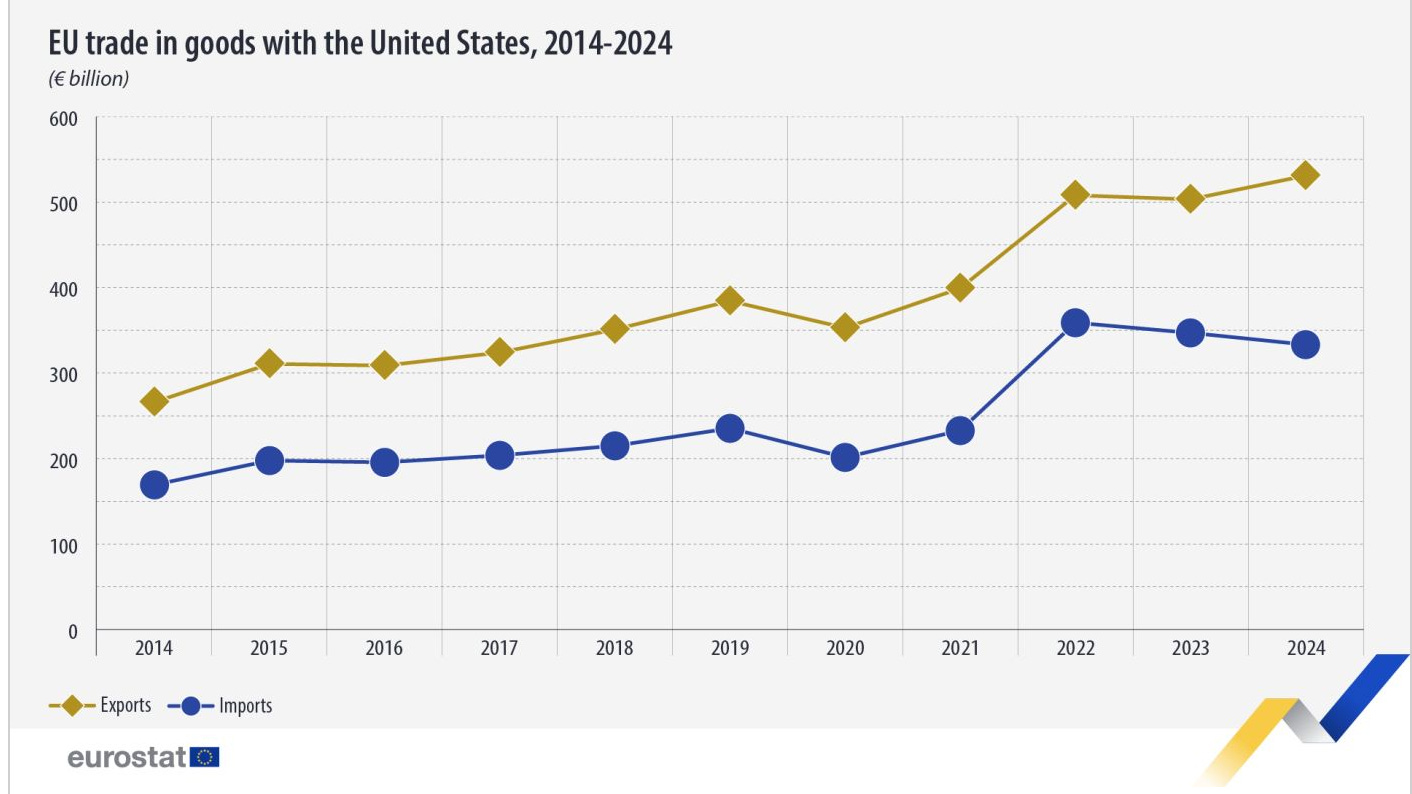

The first argument suggests that Trump has a valid point because tariffs aim to rebalance the US-Europe trade deficit. Yet a closer look reveals that while the US does indeed have a trade deficit with Europe in goods, it enjoys a surplus in services, where major American firms dominate the European market.

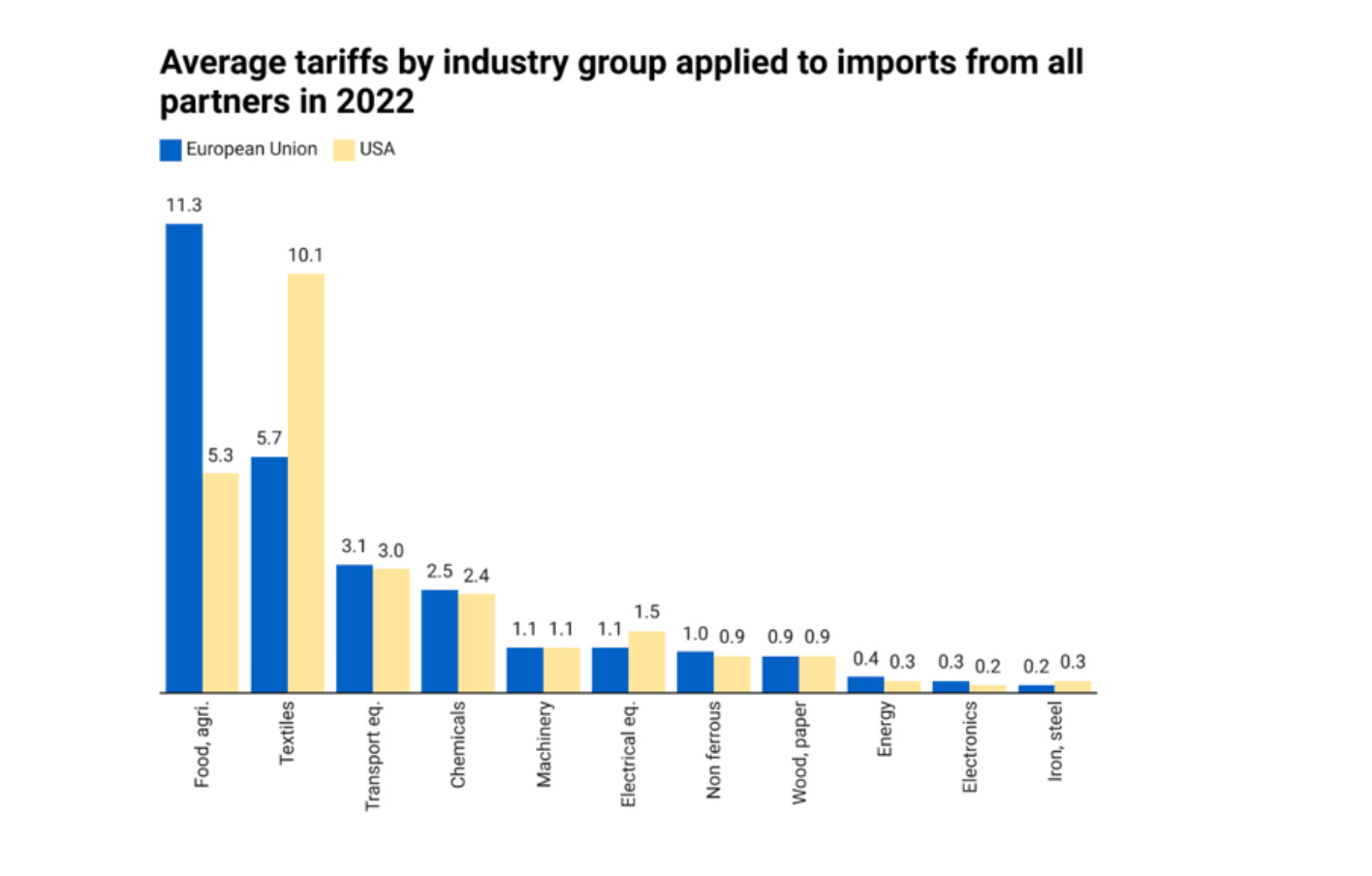

A second argument asserts that Europe already imposes higher tariffs on American goods, necessitating rebalancing. However, data indicate that tariff differences across the Atlantic are minimal. European barriers predominantly target specific American food products, especially genetically modified or chemically treated goods unacceptable to European consumers.

A third argument, proposed by some academics, suggests responding to US tariffs by letting the euro depreciate, thus regaining competitiveness.

Beyond practical difficulties, this approach would be beneficial only if initial tariffs were uniform across products, which is not the case.

Otherwise, a weaker euro could produce significant and undesirable distortions in the European economy, particularly by increasing the cost of imported commodities. Furthermore, it could open a new front with Washington, which desires a weaker dollar, as indicated by the so-called Mar-a-Lago Agreement. This could potentially ignite a currency war even more harmful than a tariff conflict.

The fourth argument is that Europe cannot win a trade war against the world's leading economy. In reality, the EU has ample tools at its disposal to bring the US administration back to reason—tools it can deploy swiftly, given the exclusive competence granted by EU treaties to the European Commission.

Although Europe remains more open to international trade than the US, the effectiveness of trade restrictions largely depends on geographical and sectoral diversification.

According to a recent study by the CEPII research center, the US relies far more on imports from Europe, particularly in strategic sectors, than Europe does on American imports.

This gives Europe the capability to impose targeted tariffs effectively. A prime example is Harley-Davidson, for which Europe, itself a major motorcycle producer, represents the iconic American brand’s largest foreign market.

Additionally, the EU has anti-dumping measures that it frequently applies against American companies attempting to undermine European competitors by selling below cost.

Moreover, Europe recently introduced an "anti-coercion" tool, already used against China, designed to discourage countries from imposing restrictive measures, such as tariffs, with the ulterior motive of extracting concessions in unrelated areas, like access to European markets for American tech firms.

Ultimately, the underlying issue is that the Trump administration refuses to acknowledge a basic economic reality: the US trade deficit is not due to tariffs and cannot be resolved by them but rather results from strong domestic demand driven by easy credit and growing public debt.

American tariffs represent a damaging error—most harmful to the US itself. The only viable solution is to reverse course, as has happened before.

Europe would commit an equally grave mistake by not responding, albeit within the strict framework of international trade rules.

The Trump administration's tariffs are pushing the US outside the rules-based system that has underpinned international relations for the past eighty years. However, the US accounts for only 15 percent of global trade.

If the remaining 85 percent unite to defend the multilateral system and open new markets, this trade war could prove a spectacular own-goal for the country that initiated it.

A first version of this article was published in the Italian daily Il Foglio

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.