Europe Reopens the Capital Markets Reform — But the Old Flaws Persist

The Commission relaunches a long-delayed project, but the absence of clear priorities and milestones risks blunting its impact. A commentary by Ignazio Angeloni

Europe is reopening the reform of capital markets. Before Christmas, the European Commission published proposals that are intended to achieve an objective that failed in 2015 and again in 2020: the creation of a single financial market that is vital and efficient.

That Europe is trying again is a good sign. The underlying problems are real. All analyses, including those contained in the Draghi report, show that the continent’s anaemic growth and the inability of its economy to generate high-value, high-income employment depend in part — only in part, as the chart shows — on the difficulty the most dynamic sectors face in securing financial resources.

It is positive that this new iteration of the project aims to involve banks, which hold an almost monopolistic position in the collection of savings. The key turning point must lie in strengthening the market by broadening banks’ business models.

That now is the right moment to move in this direction is demonstrated by the fact that, having repaired their balance sheets and profitability, European banks are seeking synergies with the insurance and asset-management sectors. This is a spontaneous process that should be encouraged by reinforcing market structures.

Unfortunately, the European initiative reproduces old weaknesses, raising fears of yet another failure.

In the interminable list of proposed legislative amendments, the guiding thread is lost: it is difficult to identify the underlying principles and to distinguish indispensable elements from those that are negotiable.

There are no clear “milestones”, with concrete, measurable objectives and corresponding timelines.

The legislative process in the Council and the European Parliament will take years; if it ever reaches completion, the world will have changed, needs and conditions will be different, and the proposals will in all likelihood have been overtaken in substance.

The experiences of 2015 and 2020 come back to mind: ambitious proclamations followed by disappointment with the final outcome.

A group of experts coordinated by IEP Bocconi, composed predominantly of market participants — banks, insurance companies, asset managers and trading platforms — presented in recent days a proposal that, starting broadly from the same analysis of the problems, puts forward a radically new and pragmatic method. It is based on verifiable objectives and anchored in the goal of freeing financial resources for innovative, high-productivity sectors.

The proposals do not require radical legislative changes, nor the unanimous adherence of member states. For the most part, a critical mass of private initiative, supported by national political backing, would suffice.

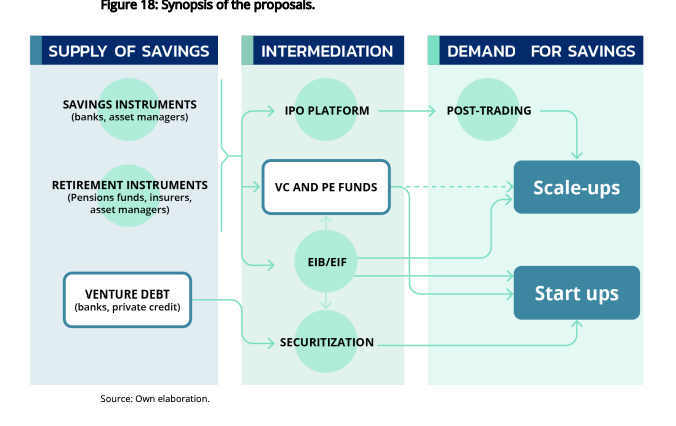

The recommendations aim first and foremost to channel household savings — of which Europe is rich — towards more productive uses. Savings are the primary ingredient of growth: the fuel that powers its engine.

Well-structured savings and pension accounts would offer savers simple, tax-advantaged channels for long-term investment.

Sweden’s investment accounts (Investeringssparkonto, or ISK) provide the model; partially similar instruments already exist and would be extended and aligned. Even a small reallocation of savings would free up significant resources to finance companies with high growth potential.

The second step is the creation of a platform for the issuance and trading of risk capital for expansion-stage companies that are ready to go public.

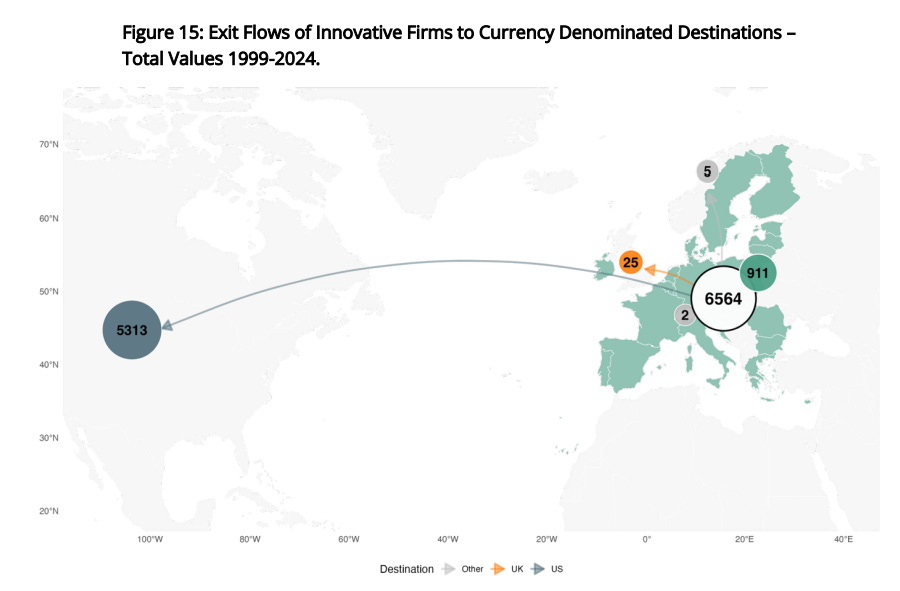

An analysis of data on 64,000 innovative European companies over the past quarter-century shows that, contrary to common belief, Europe produces a substantial number of innovative start-ups but fails to bring them to maturity.

The shortage of risk capital becomes more acute in the scale-up phase: the financing gap between Europe and the United States in venture capital, around 50 per cent in the start-up segment, increases tenfold in the scale-up segment.

The most promising companies raise capital abroad, above all in the United States, which often then leads them to transfer their operations elsewhere. Others abandon the prospect of listing altogether and are acquired.

These data show that Europe creates innovation but struggles to capture its value. A capital-raising platform with access to Europe’s pools of savings would provide the engine that, fuelled by household savings, could give companies the push they need to list and remain in Europe.

Even when fuelled and motorised, however, the growth machine cannot run safely unless it is supported by a solid structure. In Europe’s market, this structure is lacking, owing to the many obstacles that hinder the efficient creation, custody, and exchange of securities: an underdeveloped securitisation market, barriers between national securities depositories, high and asymmetric costs, and frictions in settlement.

The post-trading sector could improve through widespread use of T2S, the European Central Bank’s securities settlement system, and through simplified and interoperable custody arrangements among depositories.

A revitalised securitisation regulatory framework — transparent, standardised and market-friendly — would increase the supply of private debt securities, complementing risk capital.

The report proposes the creation of a market-making platform offering bid-ask quotes for a range of standardised securitised products. It would be private, but supported by the presence of the European Investment Bank as an investor, a role it already performs in part and which should be strengthened.

None of these proposals replaces more ambitious reforms, such as tax and insolvency harmonisation or the creation of a single supervisory authority for capital markets — obstacles on which previous reform attempts have foundered.

In the long term, Europe would benefit from a more coherent legal, fiscal and supervisory framework. But waiting for this idealised future has already cost more than a decade of delays.

The measures set out in this report offer a more realistic path, capable of delivering progress that may be limited, but faster and more concrete.

A previous version of this article was published by La Repubblica - Affari e Finanza

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.