Europe’s Banking Union needs Clarification more than Simplification

National authorities are imposing additional capital buffers on banks for reasons unrelated to the objectives set by European Regulators. A commentary by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi

The new mantra for speeding up the integration of Europe’s financial market is “simplification.” Simplification but not deregulation.

The real problem in Europe is not so much the complexity of its regulation, but rather the lack of clarity, which leaves wide room for discretion and divergent interpretations across countries — and even within EU institutions.

Take the example of banking regulation. National supervisory authorities are allowed to impose an additional capital buffer on banks in their jurisdiction, over and above the baseline set at the European level – the so-called Counter Cyclical Capital Buffer (CCyCB).

In principle, this buffer can be useful to avoid excessively pro-cyclical lending behaviour by banks. Indeed, banks tend to lend too much in good times, fuelling overheating, and to excessively restrict credit during downturns, deepening recessions.

For this reason, regulators have allowed supervisors to set a positive capital buffer when growth is above trend, and a negative one when it falls below.

When the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) was created within the ECB, this competence was left to national authorities. The argument was that business cycles may differ from country to country, even within the monetary union. But no objective criteria were defined for these national decisions — leaving each authority free to interpret the rule as it saw fit.

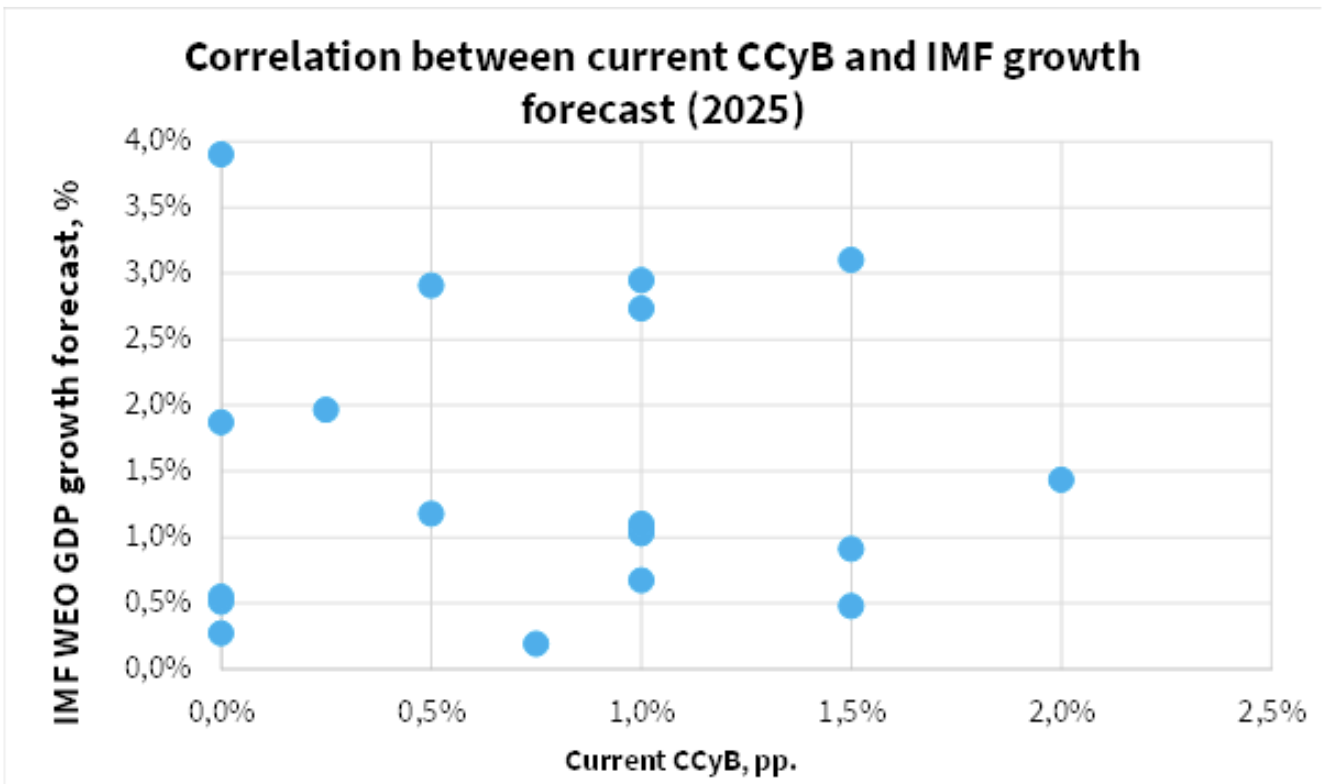

A decade of experience shows that these decisions are unrelated to national economic cycles. In other words, the counter-cyclical capital buffer has often been used for purposes that are different from the original intent.

The data are telling.

On average, euro-area banks are currently required to hold an extra 70 basis points of capital above regulatory requirements. This is puzzling, given that the European economy is growing roughly in line with potential — around 1 to 1.2 per cent per year — but still below full capacity (the so-called “output gap”). Inflationary pressures are subdued, as the ECB itself acknowledges.

Nevertheless, national supervisors are asking banks to hold additional capital to counter an alleged risk of credit overheating — a risk that hardly exists.

Moreover, the level of additional capital buffers across member states bears no consistent relationship to their relative growth rates.

Countries growing faster than the European average — such as Malta and Portugal — have a zero buffer, while Greece (25 basis points) and Spain (50) are also below the average CCyCB. Others, where growth is weaker, have instead much higher buffers: Germany (75), France (100), Slovakia, and Estonia (150). The Netherlands, whose growth is broadly in line with the euro-area average, has the highest CCyCB of all, 200 basis points — higher even than Ireland, whose economy is booming.

Finally, while some countries have frequently adjusted their counter-cyclical capital buffers, others have left them unchanged for nearly a decade, as if the business cycle had ceased to exist.

The conclusion is clear: a key instrument of European banking regulation is being used by national authorities in a discretionary and inconsistent way, disconnected from the intentions of the rule-makers. The underlying motives vary, and are rarely transparent.

The result is a fragmented and opaque regulatory framework that undermines, rather than advances, the integration of Europe’s financial markets — the very objective the ECB and the European Commission claim to pursue daily.

The solution is not mere simplification, but uniformity: a single, coherent decision-making process at the European level.

Consistency between words and actions should be the first step in any reform, including in Europe.

A first version of this article was published in the Italian daily Il Foglio

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.