External Pressure and the Fate of Iran’s Regime

Rising domestic fury and unchecked US–Israeli pressure are pushing the Islamic Republic into uncharted territory. A commentary by Nathalie Tocci

This is not the first time Iran has been swept by mass protests, nor the first time these have triggered brutal repression by the regime. Yet never before has the survival of the Islamic Republic appeared so uncertain.

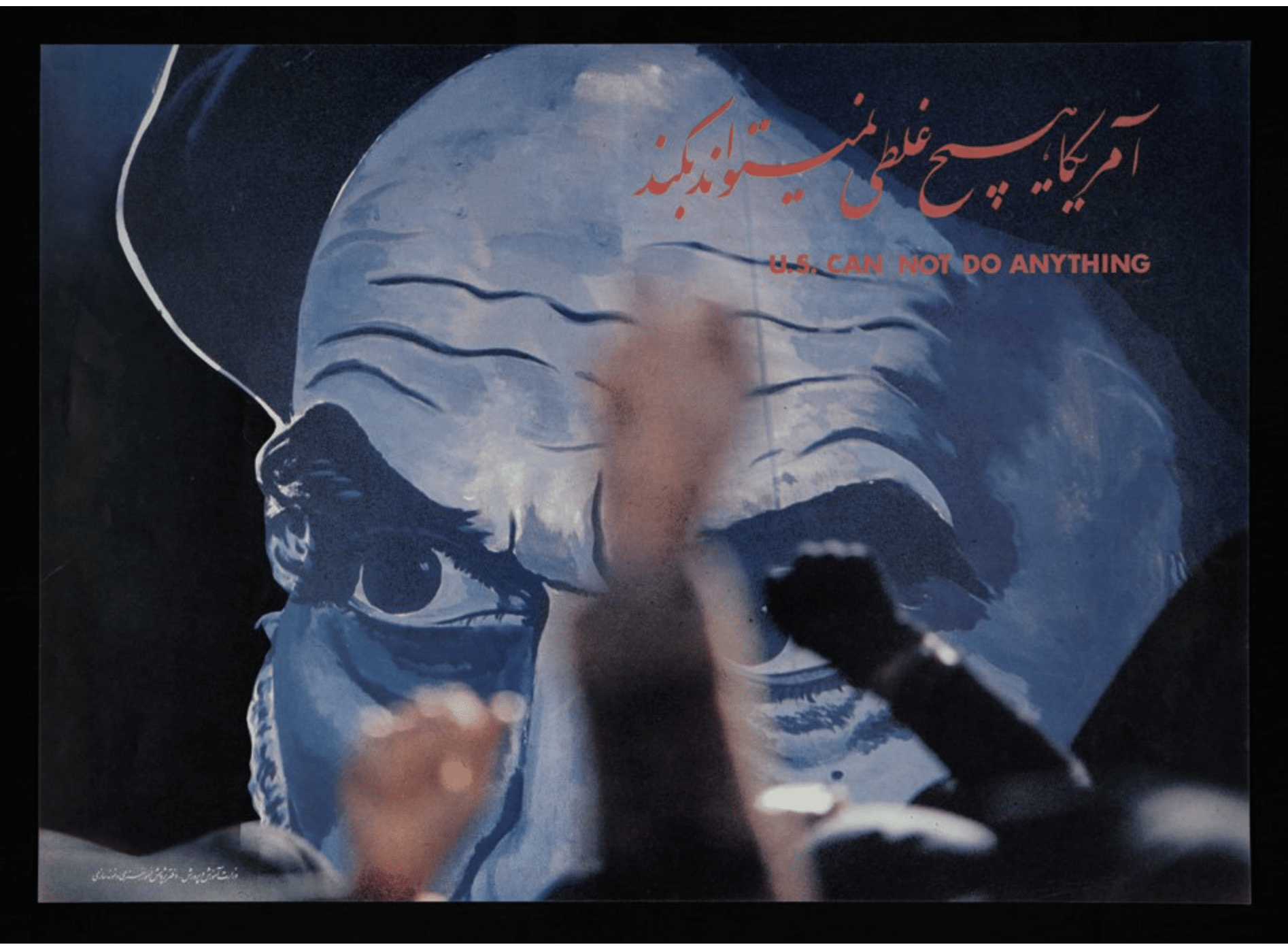

Beyond an ever more pervasive domestic dissent, Iran now faces an America and an Israel that seem increasingly unconstrained.

In this new wave of protests, the roots of internal discontent once again lie — as in 2019 — in the economy.

At the centre is the anger of a middle class of small traders, steadily impoverished by soaring inflation and international sanctions. While the demonstrations have socio-economic origins, the protesters’ demand is unmistakably political.

It is more radical than in the past, even when compared with movements of a more overtly political nature, such as those of 2009 or 2022. In short, those taking to the streets today appear unwilling to settle for partial social or political reforms and instead aim at the overthrow of the regime itself.

Yet internal dynamics alone would not be sufficient to herald imminent change. On the one hand, the security apparatus is holding and repressing. As Venezuela showed before the US attack, a regime can be deeply unpopular without that automatically spelling its end. Repression and violence can suffice to smother protest.

Syria, moreover, teaches that this strategy can “work” for a long time, even when a regime loses full territorial control: it took 14 years before Bashar al-Assad fell.

On the other hand, there is no organised and credible opposition in Tehran. Today, former crown prince Reza Pahlavi, son of the shah deposed in 1979, presents himself as an alternative and has garnered more support than in the past, helped by backing from external actors. Still, it is unrealistic to believe that Pahlavi — who has not set foot in Iran for 46 years — could successfully lead a large, complex and heterogeneous country without plunging it into chaos.

This brings us to the international dimension of Iran’s crisis. What may distinguish these protests from earlier ones is the role of two actors: Donald Trump’s United States and Benjamin Netanyahu’s Israel.

When Israel struck Iran last summer, it dubbed the operation “Rising Lion”, invoking the symbol of monarchical Iran. It has also long been known that Israel has fuelled opposition among Iran’s ethnic minorities, starting with the Kurds. Netanyahu, heading into elections, must contend with the weight of the October 7 catastrophe and the fact that Hamas, though weakened, remains standing. What better way to present himself to voters than by brandishing what he likes to call “the head of the snake” — the Iranian regime?

Then there is Trump’s United States, once - mistakenly - considered isolationist. Trump had rejected the idea of America as the “world’s policeman”, often dragged into decades-long wars at exorbitant cost and with disastrous outcomes.

Yet, like every president endowed with unparalleled military tools and near-unlimited authority over their use, he has begun to deploy them.

The difference from the past is that Trump is not interested in promoting peace and democracy, not even rhetorically respecting the rules. He has no patience for reconciliation and democratisation processes that require slow, painstaking work.

What suffices is the immediacy of spectacle and the profits of the deal, disavowing — not merely violating — any norm. Trump’s America is no longer the world’s policeman; it has become its gangster.

This is where all threads come together, casting a dense fog over Iran’s future. It is plausible that, this time, repression alone may not quell the protests.

Rising internal rage and external backing — especially if it were to translate into a new Israel–US war, longer than the 12 days of the last conflict — could lead to the decapitation of the regime. But what would happen the day after remains profoundly uncertain.

On the one hand, Iran lacks an organised opposition. On the other, a genuine regime change — not merely the removal of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei followed by a security-forces takeover — would require a far deeper US involvement than Trump is likely willing to sustain.

The outcome of a botched halfway house would be chaos — a scenario against everyone’s interests except one person’s: Netanyahu’s.

A previous version of this article was published by the Italian daily La Stampa

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.