How to Respond to Trump’s Tariffs: The Role of the Dollar

The intrinsic contradictions of Trump’s strategy will strike the United States where it is most vulnerable: inflation and employment. In the ensuing moves of this chess game, it is vital to project both strength and flexibility. A commentary by Ignazio Angeloni

In a speech delivered before the House of Lords on December 18, 1945, John Maynard Keynes uttered words worth quoting in full:

A stance similar to the one Keynes criticized back then is now driving the new American administration to adopt a hostile commercial approach toward all of its trading partners, including its closest allies. One might be tempted to respond in an equally unreasonable manner. Instead, it is better to keep a cool head, starting with a clear assessment of the likely economic impact of tariffs and what they imply for the broader global framework—and for Europe.

A tariff is effectively a tax on imports. There is no doubt that, all else being equal, such a measure pushes up prices in the country imposing it.

Signs of this are already visible in the United States: consumer surveys indicate expectations of rising prices. The Federal Reserve has already halted the downward trend in interest rates.

It is entirely possible that, in the coming months, the Fed may opt to raise rates again, thus producing the opposite effect—increases in both prices and interest rates—contrary to what Trump promised during his electoral campaign. How could such a foreseeable outcome be ignored or underestimated by the new administration?

The answer is not straightforward, because the underlying strategy has never been explicitly stated.

Stephen Miran, the White House’s chief economic adviser, argues that any inflationary effect will be offset by an appreciating dollar.

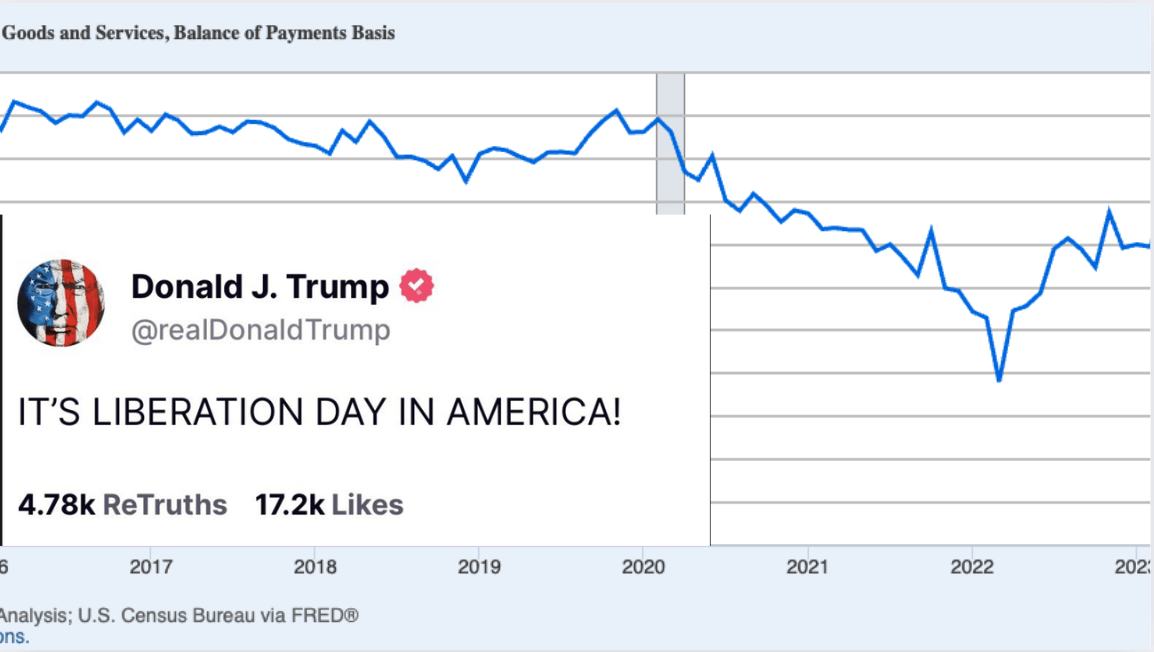

There is some truth to this: if tariffs reduce the balance-of-payments deficit, the dollar would be expected to strengthen. This interpretation is supported by what happened in late 2024, when anticipation of the new administration’s policies drove the dollar to record highs. But here is where the foundation of current US policy starts to falter, for at least two reasons.

First, a stronger dollar runs counter to the administration’s stated objective of making US manufacturing more competitive. The global dominance of the dollar—arguably a source of American strength—is not a credible component of its current economic strategy.

Given these contradictions, it is hardly surprising that in recent weeks the dollar has lost considerable ground, almost wiping out its previous gains. The second reason is that tariffs are being deployed to achieve various, sometimes incompatible, objectives. In many cases, the threat of tariffs is used to extract concessions on unrelated issues—immigration or crime, for instance—and then rescinded once those concessions are secured.

Such erratic behavior fuels uncertainty, which has a recessionary impact on the economy. Worse still, it could induce both inflation and recession—the opposite of the booming economy promised on the campaign trail. In his latest press conference, Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell explicitly warned of the risk of stagflation.

From our European perspective as historic US partners—and as allies committed to an open and rules-based international trading system—this approach poses multiple and complex challenges. Tariffs, even if not directly levied on us, can still exert recessionary effects.

Uncertainty, moreover, discourages investment. Another particular concern is the dollar’s volatility: if it appreciates against the euro, then the inflationary effect initially confined to the United States can be exported here as well. The stagflation dilemma that already troubles Powell could soon become a headache for Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB.

Discussions on this side of the Atlantic have focused on how the EU should respond: should it impose retaliatory tariffs or wait and attempt to negotiate a better deal?

Precisely because many US actions at present seem more like part of an aggressive negotiating stance rather than a coherent long-term strategy, a response is necessary.

There is no doubt that what is happening today is part of an ongoing negotiation with uncertain outcomes. Yet for this very reason, a strategy of “respond first, then negotiate” should now prevail over “wait and negotiate in the meantime.”

Time will work in our favor if the intrinsic contradictions of Trump’s strategy end up hitting the US where it matters most: inflation and employment. In the subsequent moves of this chess game, it is essential to demonstrate both resolve and flexibility.

An Italian version of this article was published in the newspaper Il Foglio.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.