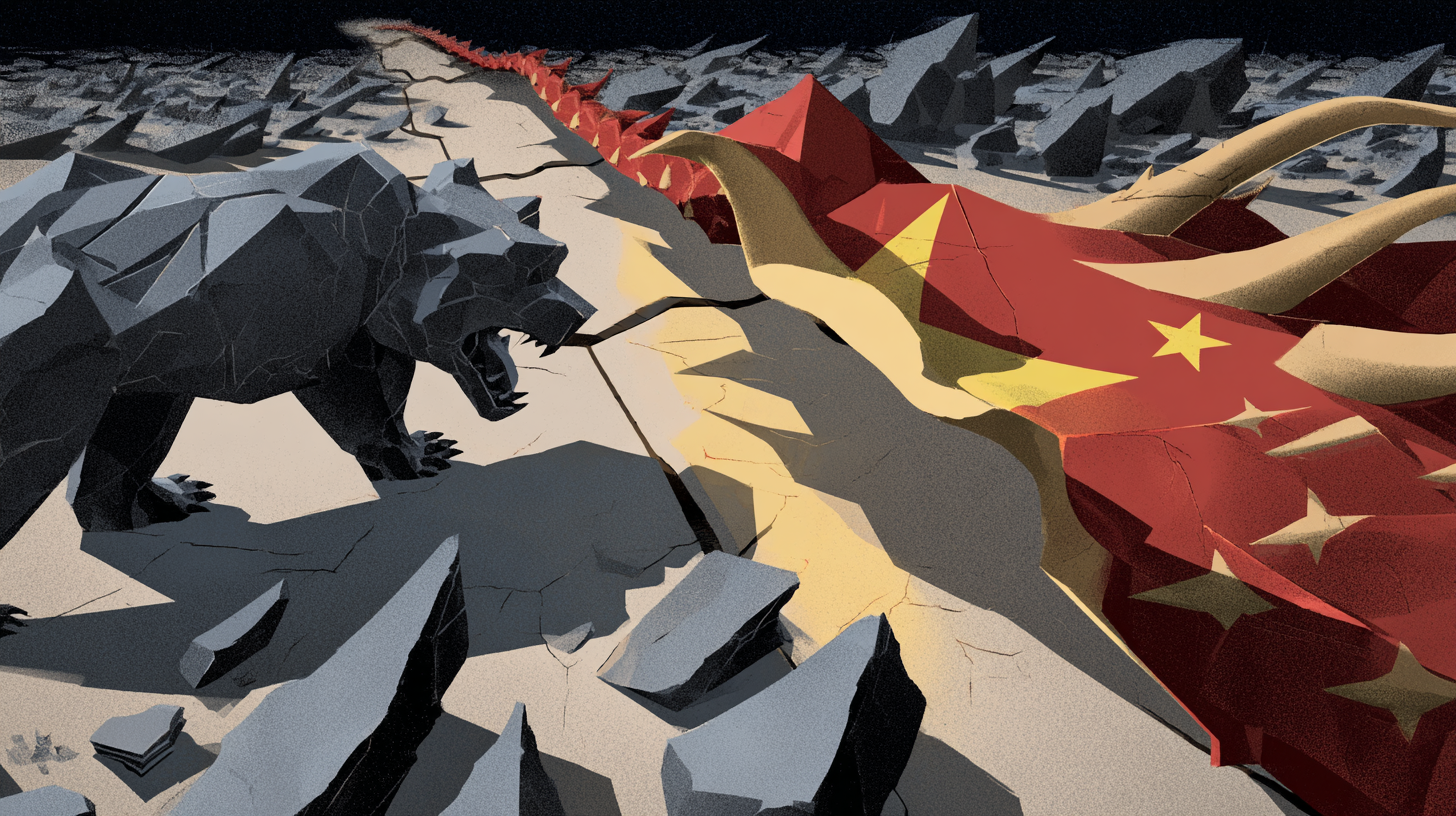

How Trump’s National Security Strategy Recasts Russia and China

If the US aims at mobilising its allies against China’s “predatory economic practices”, as it states in its NSS, it should refrain from criticizing them. A commentary by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi

Once again, attention turns to the foreign policy strategy document published a few days ago by the Trump administration. Much has been written about the new stance towards Europe, but the changes in US relations with Russia and China are no less significant. A comparison with the strategy document released in 2017 is instructive.

Starting with Russia, the first Trump administration argued in 2017 “Although the menace of Soviet communism is gone, new threats test our will. Russia is using subversive measures to weaken the credibility of America’s commitment to Europe, undermine transatlantic unity, and weaken European institutions and governments.”

Eight years later, President Trump appears to have changed his view. In the latest document, it is stated that “following Russia’s war in Ukraine, … many Europeans view Russia as an existential threat.” Despite the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia is now portrayed as a threat primarily to Europeans — no longer to Americans.

The role of the United States is no longer described as “working together [with Europe] to counter Russian subversion and aggression”, as it was eight years ago, but rather as engaging diplomatically “to mitigate the risk of conflict between Russia and European states”.

With the benefit of hindsight, the 2017 document proved prescient when it warned that “Russia aims to weaken US influence in the world and divide us from our allies and partners”. That prediction has now clearly materialised.

When it comes to China, the American attitude appears less transformed than resigned.

The document acknowledges “the mistaken assumption that by opening our markets to China, encouraging American business to invest in China, and outsourcing our manufacturing to China, we would facilitate China’s entry into the so-called “rules-based international order.” This did not happen. China got rich and powerful, and used its wealth and power to its considerable advantage.”

Yet the document offers little guidance on future policy, beyond general calls to put an end to “• Predatory, state-directed subsidies and industrial strategies; • Unfair trading practices; • Job destruction and deindustrialization; • Grand-scale intellectual property theft and industrial espionage; • Threats against our supply chains that risk U.S. access to critical resources, including minerals and rare earth elements”.

Notably absent is any renewed emphasis on tariffs as a tool to counter Chinese trade practices. Evidently, the experience of recent months has left a bitter aftertaste. The tariff escalation that began with “Liberation Day” on April 2 failed to move the Chinese authorities, who — unlike their European counterparts — immediately adopted retaliatory measures against the US.

These began with restrictions on imports of agricultural products, notably soybeans, directly hitting incomes in the Midwestern states that traditionally support the Republican Party.

The most effective countermeasure, however, was China’s voluntary export restriction of rare earths, which are essential for a wide range of strategic industries, from automotive manufacturing to aerospace. China had long prepared for this, securing supply agreements with raw material producers and establishing a near-monopoly in refining capacity.

The effectiveness of China’s response pushed the Trump administration to reverse course — with an additional cost: lifting restrictions on semiconductor exports to China, particularly those affecting Nvidia chips, which are critical for high-tech production.

The US ban collapsed in the face of the threat of a rare earth embargo.

Meanwhile, China’s trade surplus has risen above $1tn, the highest level on record. Chinese exports are flooding industrialised economies through new channels, at increasingly competitive prices.

The US strategy document concludes that “the United States must work with allies to counter [Chinese] predatory economic practices and use economic power to safeguard leadership in the global economy and ensure that allied economies do not become subordinate to any rival power”.

This is an objective that Europe can readily share. But genuine “co-operation” with allies would also require refraining from criticising their political systems — and from subjecting them to discriminatory measures.

A first version of this article was published in the Italian daily Il Foglio

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.