If Trump Weakens the Fed, the ECB Must Step Up

As pressure on central banks grows, the Eurozone’s institution cannot avoid greater responsibility. A commentary by Ignazio Angeloni

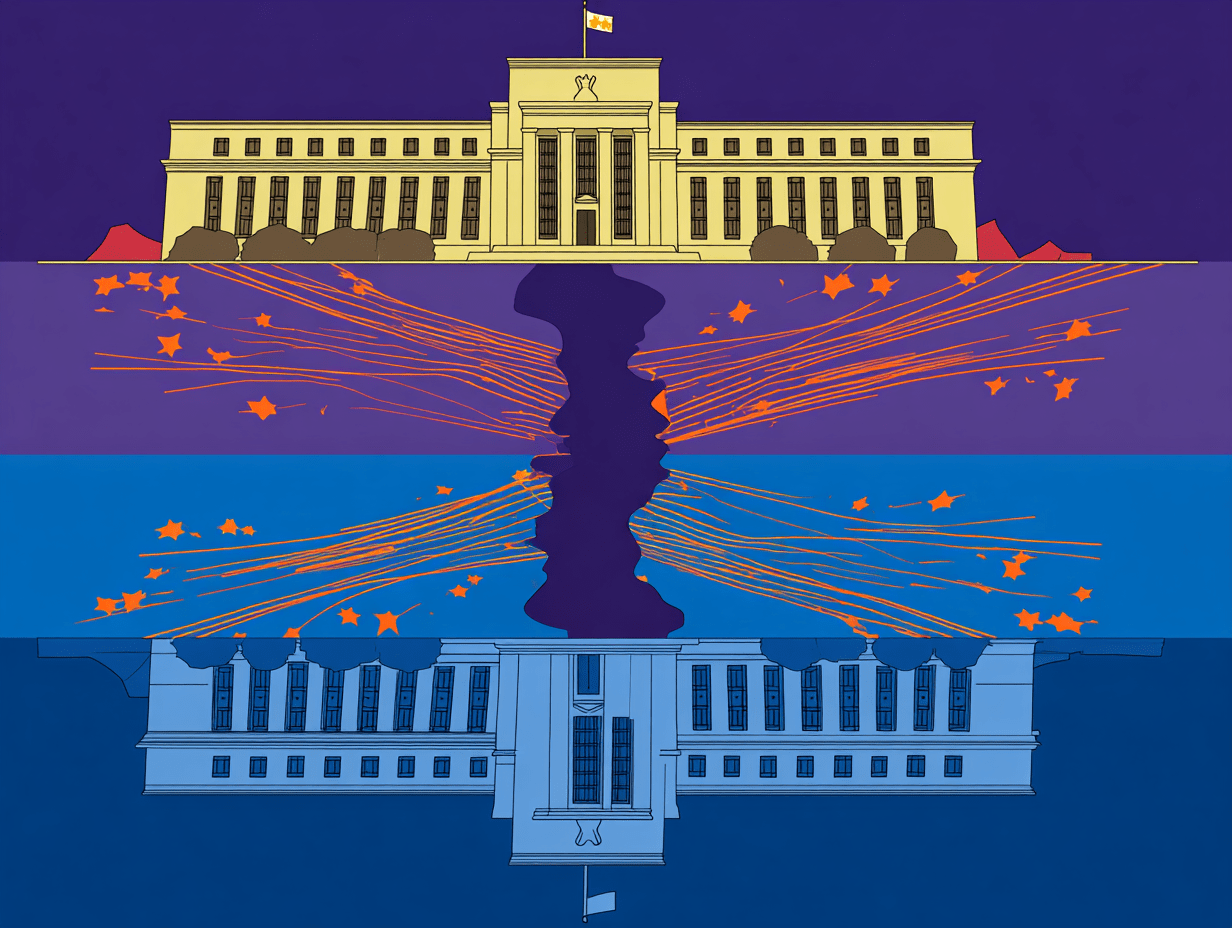

The emerging risks to the independence of the US Federal Reserve are sending tremors through global finance. More will come as President Donald Trump’s strategy to gain more direct influence over the Fed unfolds.

Central banks around the world ought to prepare, because pressure on them will increase and so will their responsibility. The European Central Bank, presiding over the second most traded currency in the world, is first in line to be affected.

It may seem a long shot that the safeguards around central bank independence, supported by virtually all political sides and experts, can be overridden. But let’s not be fooled. Even if today’s attacks — most notably attempts to sack Fed governor Lisa Cook — are delayed or even fail, the remaining three and a half years are more than enough for Trump to achieve his goals.

In the last quarter century, the Fed and ECB joined in a partnership that provided inspiration and leadership to global central banks. Fed officials advised the ECB at key junctures: when it was designing its monetary policy strategy, starting to operate in the open market and building a banking supervisory arm.

The influence went both ways: the ECB inspired the Fed’s 2011 decision to hold press conferences after policy meetings. And the ECB’s decision in 2014 to start annual conferences in the Portuguese resort town of Sintra originated from its desire to have a European version of the yearly central banking meeting at Jackson Hole. Replace the Tetons with a nearby ocean, and the two events look very much alike.

This unique relationship may be tested if the Fed’s independence is eroded — and the ECB may have to take on more of a role as the standard-bearer for valued central banking traditions. It is not too early for it to take the lead in strengthening co-operation with other central banks in two areas that could be particularly fruitful.

One is digital currencies. The last few years have seen a flurry of novelties: from the idea of issuing central bank digital currencies to the rise of cryptoassets, particularly stablecoins, as a possible replacement of traditional means of payment.

These stablecoins are digital tokens pegged to major currencies and other assets. Clearer guidance from the central banking community on how future payment systems should look like would be helpful.

It is unconceivable that the handful of central banks issuing globally traded currencies can each go their own way in such crucial and interconnected matter.

A consistent strategy is therefore needed. After the decisions by the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England to shelve their central bank digital currency plans, the insistence by the ECB on working towards a retail-based digital euro is a source of confusion. It also delays the development of a common line on how to control the threat that lightly-regulated dollar-denominated stablecoins pose for financial stability.

The key question is how best to combine central bank involvement in digital currencies with the growing use of blockchain technologies, in order to improve areas of payment systems which underperform without disturbing those that work well.

A prime area for intervention is the cross-border payment system, which still runs on uncompetitive, costly and unsafe arrangements between so-called “correspondent banks”. Absent John Maynard Keynes’ idea for an International Clearing Union or world central bank, the second-best alternative seems to be a distributed ledger among the relevant central banks.

The ECB could also usefully facilitate policy discussions when it comes to international crisis management. The framework successfully tested in the great financial crisis of 2008 and during the 2020 pandemic is based on currency swaps with the Fed acting as last-resort provider of dollars. But these days there is no guarantee that a US central bank controlled by the US president will perform that role as effectively and unconditionally as it did in the past.

Recent analysis by Oxford economist Robert McCauley shows that while only the Fed can act as unlimited provider of the US currency, a combination of other central banks could mobilise sufficient dollars in a crisis through a “coalition of the willing”.

Any diminution of the Fed’s independence will have major consequences for international finance. For the ECB, the youngest of the big central banks globally, it is a call to take responsibility and action. It can rise to the challenge, and hopefully will.

A previous version of this article was published by the Financial Times

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.