Imperial Modernity

Beware of Imperial Powers. They’re more alive than ever. A commentary by Andrea Colli

I have been teaching an undergraduate course in Global History for the past five years, covering the period from the end of the Napoleonic Wars to today.

The main aim of the course has so far been twofold. On the one hand, to teach students what happened in such a short (for historians) span of time, and how much of the present bears the (stinky) scent of the past.

On the other hand, the purpose is to teach a sort of “global history of global phenomena”, for instance, global economic and social integration, from a longer-term perspective. A short-term lens often fails to provide a clear understanding of our present.

In general, the course has been well received by the students (for instance, the classes dedicated to the post-1989 “acceleration” of history are particularly popular). However, the first class that I teach to set the stage always catches my students by surprise. I do not blame them too much: I decided to start the course with a class on Empires. Then, I really see these Gen Z—soon Gen Alpha—students struggling to understand why they have to deal with something so conceptually belonging to the distant past.

Then, I start suggesting that, even if they live in a borderless global environment, far from being dinosaurs, Empires have long shadows: for instance, each of them belongs to a more or less benevolent colonizer or to a former colony. Anyway, the smell of dust is always there, aggravated by the fact that there are no more Emperors around – except for the Japanese one.

Anyway, for a global historian, or a historian of globalization, as one prefers, empires remain important, at least for two reasons.

One, rather whiggish: Empires have not always been demonic, oppressive political artifacts. Frequently, these supranational polities were able to create (at some price) realms of coexistence, spaces for borderless artistic and cultural exchanges, and also, for ideological “mixing”.

Second, Empires, as places of trade and technological interconnections, played a (partial) integrating role of segments of the global economy, in their endless efforts to build an acceptable integrated space, for instance, through technological means such as canals, roads, railways, and an impressive amount of public works.

Are Empires back?

History has recently become provocative in several ways and helped spice up my lectures about Empires in an unexpected way. In recent years – let’s say after the Russian aggression against Ukraine - the word “Empire” resurfaced forcefully in the jargon of international politics, almost everywhere, even if particularly we, Western Europeans, remain allergic to the term, with some good reasons. Decades of sheer anti-imperialism have equated the idea of empire to a political artifact built on violence, conquest, authority, and contemptuous inequality. But there are at least two reasons to rethink modern versions of Empires, to understand which historical knowledge is useful. One reason is again “historical”. The other has to do with our dramatic present.

The first reason is that supranational institutions (you may call them Empires if you like) never disappeared. Some re-emerged immediately – or better, during the decolonization wave of the 1960s, as new political concepts based no longer on conquest, but on “invitation” and convenience, as the Commonwealth or French West Africa.

In 1956, the year of the Treaties of Rome, celebrating the birth of the European Community, geographic maps still showed Algeria as part of France (notwithstanding a bloody independence war underway).

Belgium was firmly keeping the Congo under its heel, ready to kill in cold blood its legitimate leader, Patrice Lumumba.

The Netherlands reluctantly ceded its lucrative outposts in the West Indies. Luxembourg was doing the same dirty business as Congo, while Italy still held protectorates in the Horn of Africa.

Paradoxically, the least culpable of the bunch was former Nazi West Germany.

Luckily, at least in the European case, soon the concept of multilateralism prevailed over that of imperialism, and by 1962, the year of Algerian independence, all these imperial reminders were over.

Moreover, there have always been Empires reluctant to define themselves as such but behaving as if they were. Even if openly anti-imperialist, like China, which in 1950 ended the longstanding isolation of Tibet.

Imperial aspirations have always driven the Cold War chessboard, of course, not to mention the two main superpowers (with a key difference between an “irresistible”, centripetal empire, as the American, which enlarged its borders by rebuilding the global economic integration and the Soviet one, based on hard power and entrenchment).

The second reason, much more important today, is that we thought that imperial aspirations were over and dead when the world turned towards multilateralism. We, however, forgot one of the basics of the dismal science, geopolitics. That is: Empires are real, want to control space and land, resources, and, if possible, minds. They want to master space. They are Star Wars. And it does not matter if now no one of the present (none of today’s) great powers even dares to brush up that “scandalous” word.

The nine presents of Empires

Roughly, Empires and great powers have nine elements in common, which appear to be remarkably resilient.

First: Expansion. Empires are around us, both in terms of territorial extension and willingness to expand. Let’s take their least symbolic characteristic, the most distinctive: territorial enlargement.

Probably, the most “elegant” formulation of this logic goes back to 2010, when at a meeting of the ASEAN countries in Hanoi, the then Chinese foreign minister, in response to the complaints about Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea, remarked: “China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact”.

All today’s great powers have continental, one can say “imperial”, extensions. If not yet, they struggle to achieve it.

Second: Rebuttal. Another contradiction typical of imperial attitudes was a fierce rebuttal of multilateralism, which is a trait of today’s great powers. Empires tended to act in a quite selfish way, watching their own security and barely building alliances with similar empires.

Empires historically acted through bilateral or restricted mutual defensive alliances (particularly during the Second European Concert of Powers – which curiously seems to wake up again, but at a more global level, with Mr. Trump’s recently announced Board of Peace, or BoP).

Third: Transactionalism. A consequence of the second point is that, simply, Empires (or great powers) not only saw multilateralism with suspicion but had an approach aiming at maximizing individual gains – nicely, apparently, 1 billion dollars is the fee that grants you the permanent membership in the BoP.

Fourth: Violence. Old and modern Emperors seem to appreciate might when it is equated to right. One interesting common feature is the taste for violence: domestic violence, killing of opponents, but also a concept of violence which does include what is commonly called soft power. The only ways they are gracefully available to ally with minor powers are:

a) When they’re in some way dangerous as nuclear/fundamentalist powers – Pakistan, or North Korea

b) Potentially useful (as a vast number of resource-endowed African, Asian or South American States, or a bunch of useless but geographically valuable entities in the Pacific Ocean)

c) In both the previous cases, all these places are considered no more than suzerain territories (an esoteric term which defines a grey area between a State’s full sovereignty in internal politics, but a limited sovereignty when it comes to international affairs – see later point 7)

Fifth: Contempt. Imperial powers have not been “polite” at all. Even today, education means being able to deal with lesser powers on an equal basis of common respect for law, sovereignty, and good manners.

Above all, it means the presence of “liberal” attitudes towards others, even when they have different ideas. And to have a “sense” of their past sins.

When in his super famous “Iron Curtain Speech” Sir Churchill ironically blamed his wartime (in his words, comrade) Stalin for his postwar aggressive posture, and after a long tirade on what the future equilibrium of (Western) Europe should be or should not be away from the devils of communism, he quietly superseded the past role of the largest imperial nation the World had seen in its history, the implacable holder of colonies and protectorates, the long standing culprit of Atlantic slavery system and of the poisonous subjugation of China, as well as the those responsible for the post-Ottoman political disasters in the name of Persian oil.

Apparently, politeness is not at all an attribute shared by super or great powers today. How Mr. Trump approached Denmark and the EU recently over Greenland is just the last, and probably the most vulgar example.

Sixth: Display of power. Another recent, but also long-standing characteristic of Empires, which today’s great powers eagerly pick up, is the irresistible attraction for symbols of power. Empires do love symbols of power. I understood this reading an article by Krzysztof Pelc published in January 2026 in Foreign Policy.

I find his argument compelling because, although he approaches the issue as a political economist typically concerned with the question “cui bono?”, he deliberately reverses the analytical lens: in his words, “not who gains, but what is being staged”.

Fascist Italy, for instance, staged its conquest of (at that time) useless Libya and territories in the Horn of Africa just for displaying power and reminding the World of the once supercontinental Roman domination. Aesthetic, not interest. And now?

Fentanyl is killing Americans, much more than cocaine. Venezuela has the vastest oil reserves in the World, but that oil is expensive to extract and transport (according to Exxon’s CEO). Greenland is not formally but militarily American, since 1951, in virtue of a security treaty. To be honest, Taiwan is much more necessary for the World economy as it stands now than as a part of the Great, Unified China. And so, what? Empires do love territorial power. Just that.

Seventh: Hemispheric control. Empires needed large territorial dimensions. Empires survived through physical outreach. And super and great powers look for hemispheric control, both directly and indirectly.

This can be rebuffed (for how long, it depends on how much a middle power decides to be a middle power (ask Venezuela, Cuba, Colombia, but please question Argentina, maybe). Spheres of influence are necessary buffers, and the logic of great powers is to treat middle powers as pawns at their disposal, even “exchanging” them in the name of a supposed equilibrium. Empires turned terribly ferocious when one endangered their integrity, unless they decided to come to terms with the others in the club.

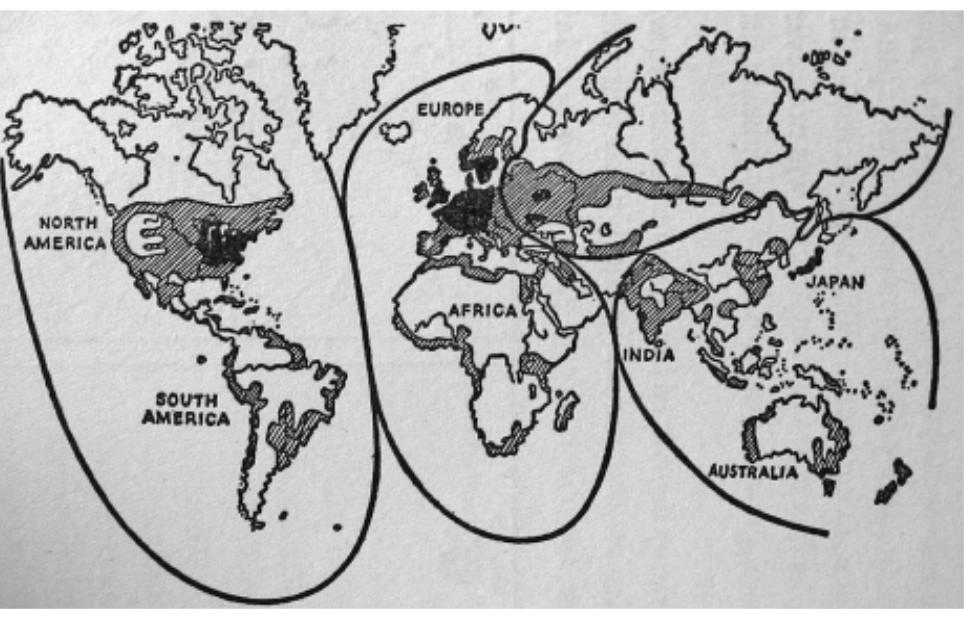

In the 1930s, the German Geopolitik School at the University of Munich imagined a really good structure of World Order based on “pan regions”, that is a version of “spheres of influence” in which several great powers were supposed to establish a longstanding equilibrium based on hemispherical areas of control.

Protagonists here were the great powers of the time: the US, Germany, the Soviet Union, and Japan. One can easily put new labels on the map, updating it to the present.

Fig. 1 Pan-regions in the view of the German Geopolitical School (1930s)

Eighth: How are Emperors born? Because of what I said above, empires, particularly the new ones (here I am consciously mixing the two things) are terribly violent, for one simple reason.

They forgot how to deal with the difficult art of power politics as it was crafted during the post-Napoleonic restoration period. But Empires and modern great powers need emperors. Of course, we have some of them around, even if not named as such, (invariably, all male – this is something gender sociology must explain).

I am not, of course, an expert on autocracy, as my friend Sergei Guriev masterfully explains in his book Spin Dictators. But one question I am not able to answer in brief is: how is an Emperor born? Has populism, or something else, some fault in this? As a historian, I look backward, and the answer is more yes than no.

Nine: the rise of the “Real” State. In 1996, a political scientist, Richard Rosecrance, who unfortunately recently passed away, in a famous article published in Foreign Affairs proclaimed, The Rise of the Virtual State. The article is a sort of breakthrough piece, even if I must admit, not one of Rosecrance’s best works.

The paper has a basic message: the post-1989 World was going to dissolve into a borderless community in which the real protagonist was, in the end, the multinational corporation.

I understand Rosecrance, a realist who passed to more liberal positions, as I understood all of us, when young students, sang the Scorpions’ Winds of Change with a glimpse of hope in a finally multilateral world.

But we all were naive.

Afterword

Let me sum up:

a) Empires, old and new, need a scale, a physical scale. The thirst for territory is not over; it is brutally there. Only, the notion of imperial reach has enlarged and modernized: technology, orbital space, power, soft power, and terror. These are the new imperial courtyards.

b) Empires, old and new, need, of course, land, since territory provides resources: cheap labor, energy, and new materials.

c) Land, as classic geopolitics tells us, is also a buffer against aggression, even in times of airstrikes and drone strikes.

d) Land, labor, infrastructures such as ports (Panama), in general, hotspots have another advantage (and a curse): they carry resources and in a globalized world are the locus of the indispensable global value chains. A great power with hemispherical control not only masters natural resources, but also the lifeblood of the economy and mankind’s daily life: infrastructures and, for instance, sea lanes.

e) Last, but not least, land (and seabed, which is indeed land) is indispensable for another lifeblood: communication. 95% of all our transactions pass through undersea cables.

So, beware of Imperial Powers. They’re more alive than ever.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.