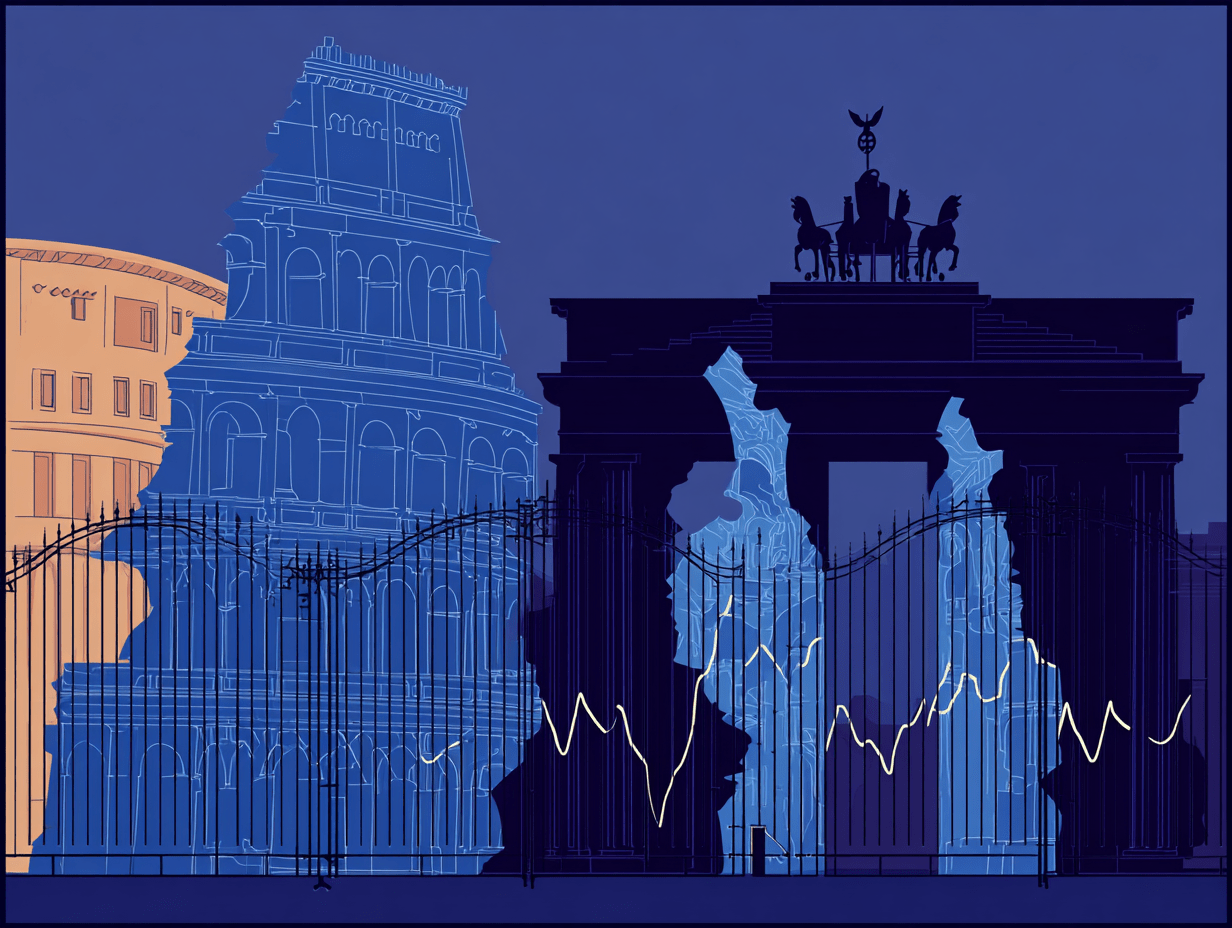

Italy’s Debt is Steadier — but Germany is No Longer a Flawless Benchmark

The fall in the BTP–Bund spread says more about Berlin’s fiscal drift than Rome’s newfound virtue. A commentary by Ignazio Angeloni

For years, Italians have treated the spread between Italian and German government bond yields as the ultimate thermometer of fiscal health. We panicked when it rose, cheered when it fell, and judged governments almost exclusively on the basis of that fluctuating number.

The underlying assumption was that the German rate provided an infallible benchmark of financial reliability — a constant target to approach, or at least not to deviate from too far.

That assumption no longer holds. Or rather, it is no longer sufficient on its own. Germany is not the paragon it once was. In several dimensions, in fact, but let us confine ourselves here to public accounts and the debt issued to cover them.

Since the pandemic, Berlin has failed to restore fiscal balance. From 2024 onwards, the situation has worsened, weighed down by military and infrastructure spending commitments that will only increase, while unpopular tax hikes have proven politically ineffective.

This shift has consequences for Italy. The fact that the spread has fallen close to — or even below — historic lows, helping to justify Fitch’s recent upgrade of Italy’s sovereign rating (from BBB to BBB+, still the lowest in the EU apart from Greece), owes less to renewed investor enthusiasm for Rome than to Berlin’s fiscal slippage.

The story of the past three years under Giorgia Meloni’s government is straightforward: after an initial year of uncertainty — new coalition, high inflation — Italian bond yields stabilised around 3.5 per cent. Meanwhile, international rates swung with global volatility, while German and especially French yields rose as domestic troubles mounted.

This is why the spread has lost much of its diagnostic power. From now on, the real test of Italy’s fiscal management will be the absolute cost of its debt.

The government deserves credit for its prudence in a turbulent global environment; the stability of long-term yields in the past two years is evidence of that.

Yet borrowing for ten years at 3.5 per cent may be risky for a semi-stagnant economy.

The IMF projects growth of just 0.5 per cent this year, edging up to 0.8 per cent in 2026. With inflation below 2 per cent, stabilising the debt from 2026 onwards would require average real growth of 1.7 per cent per year — far above Italy’s recent performance.

The quality of public finances raises further concerns. Coalition pressures mount to spend the fiscal windfall from higher tax revenues, despite Finance Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti’s opposition.

Calls to block the scheduled rise in the retirement age persist, even as demographic ageing accelerates.

Meanwhile, tax compliance is being undermined: according to the Osservatorio sui Conti Pubblici Italiani, the government’s latest amnesty not only rewards evaders, but disproportionately benefits the biggest ones.

Italy has made progress, but the work is far from complete. Does the Fitch upgrade amount to a full endorsement of Rome’s fiscal stance? Only halfway. The rest is encouragement.

A previous version of this article was published by MF - Milano Finanza

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.