Market Making as Crisis Management: A History of the 1985 White Paper

At the Castello Sforzesco, in the 1985 meeting, the European Council agreed with the Commission’s conclusion that an internal market could provide the economic and social “crisis management” the Community needed and secure its global economic competitiveness. A paper by Grace Ballor

-

FileBallor WP_IEP- annualevent_final.pdf (2.61 MB)

Executive Summary

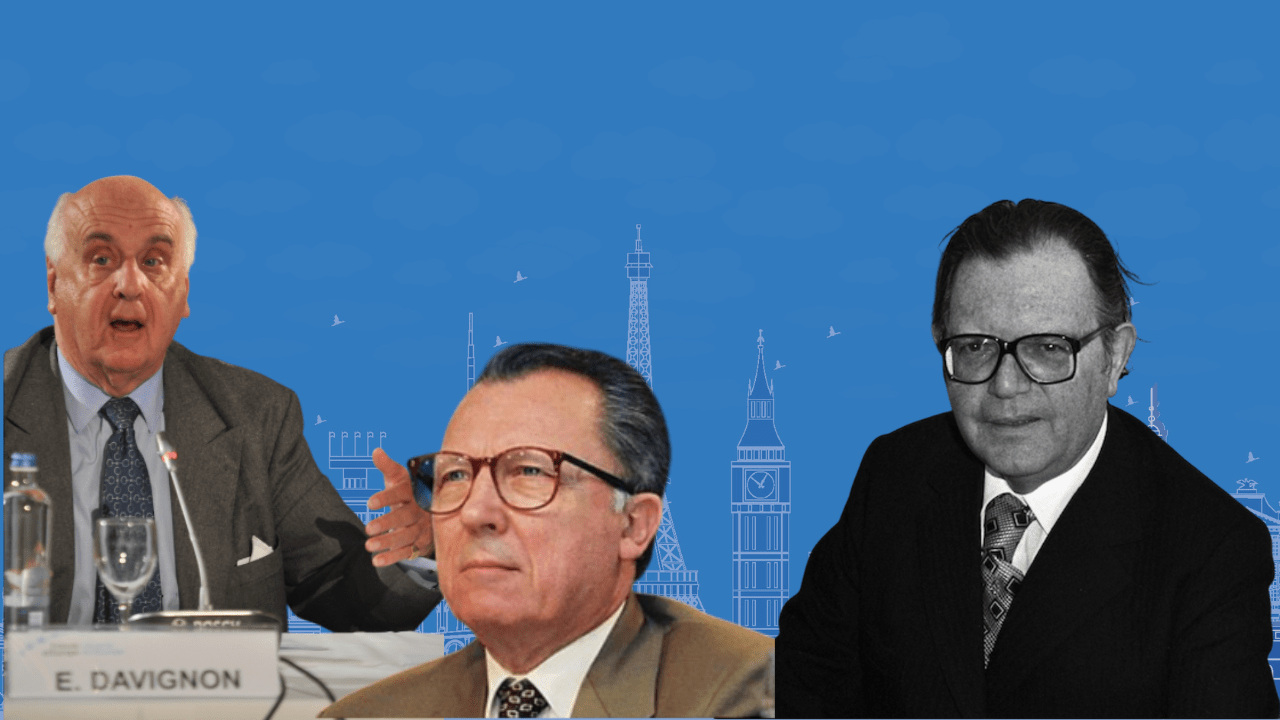

In January 1985, the newly appointed members of the European Commission gathered around their conference table at the institution’s Berlaymont headquarters in Brussels to determine how to make a single, internal market. Their primary objectives under new Commission President Jacques Delors were to shepherd the European Economic Community (EEC) out of the crises of the previous decade and reinvigorate the “stalled” European project.

Even before officially taking up his position, Delors offered several proposals to achieve those ends, ranging from common defense to monetary union. Above all, it was the agenda of full internal market integration that won unanimous approval among member state governments looking to Brussels for solutions to widespread economic and social problems. By facilitating the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people across member state borders within the EEC, an internal market could remedy the region’s economic and social crises, re-energize growth and employment, and re-legitimize the Community, reasoned national officials and regional policymakers. They believed the right market policies could also bolster European competitiveness in a global economy full of rivals from other regions and lay a foundation for further integrative aims like political, economic, and monetary union.

The diversity of Commissioners complicated debates about how to make a market. Not only did the institution’s composition change often, given the four-year terms of its members during the late 1950s to early 1990s, but enlargements also increased the number and widened the perspectives of its policymakers. Commissioners hailed from countries with drastically different economic systems and policy approaches, ranging from German ordoliberalism to French dirigisme to British neoliberalism, competition between which played out in policy meetings about market integration in the 1980s as much as it had in the EEC’s efforts to develop a collective response to the problems of the 1970s.

When they designed the Single Market, few of the Commission’s then 18 members had training in economics. Some, like the Dutch Frans Andriessen and Manuel Marín from Spain, were lawyers before entering civil service; others, like António Cardoso e Cunha from the new member state of Portugal, had corporate careers before joining the Commission. Such diverse national and professional backgrounds informed their many views on the place of business in the Single Market.

For liberal Commissioners like Peter Sutherland, who later became the founding Director General of the World Trade Organization (WTO), regulation posed a threat to the primary goal of growth. For those of more socialist persuasions, like the Italian environmentalist Carlo Ripa di Meana, the market was only worth pursuing if it could provide a path to humane, cohesive, sustainable, and equitable development—not guaranteed by the “invisible hand” of market forces.

In some ways, these diverse perspectives enriched the work of market making. At the same time, discrepancies within the institution underscored the challenges of intergovernmental consensus and left its policymaking endeavors open to outsized influence from those with vested interests in certain market outcomes. Despite their differences, however, policymakers in the Commission developed a comprehensive program for market integration that relied on the regionalization of business.

This paper, derived from a chapter of my forthcoming book with Cambridge University Press, Enterprise and Integration: Big Business and the Making of the Single European Market, historicizes the Single Market Program, which transformed regional economic, commercial, competition, industrial, and social policies and remade the relationship between firms and European governance. It contextualizes the challenges that motivated the EEC to pursue market integration and argues the Commission viewed market making as a means of economic and social “crisis management.”

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.