Monte dei Paschi’s Mediobanca Takeover Raises More Questions than Answers

Rome has long been better at divisions than mergers. Now, Italy’s newest banking giant must prove it has a credible plan — and the right people to execute it. A commentary by Ignazio Angeloni

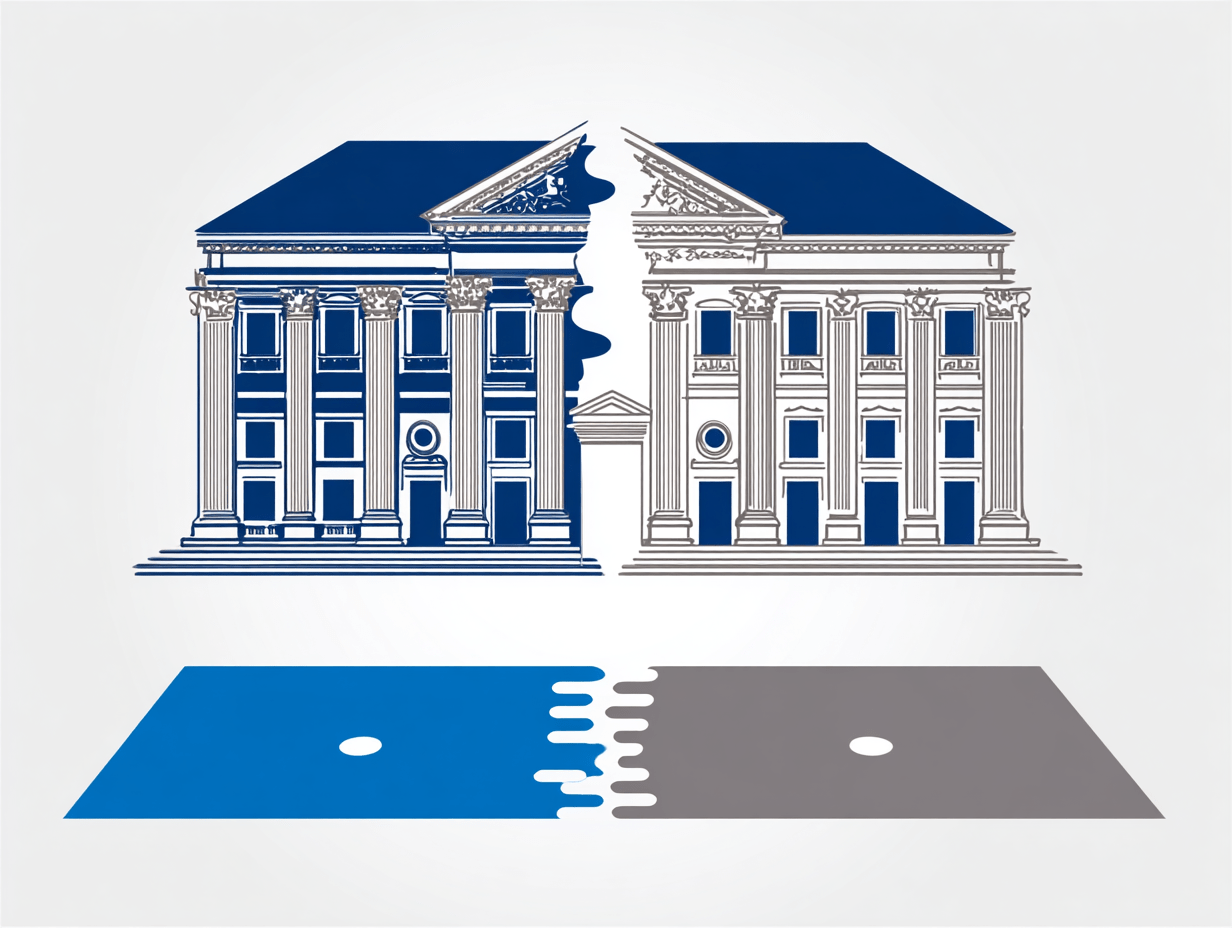

The takeover of Mediobanca by Monte dei Paschi, confirmed on Monday with acceptance levels reaching 62.3 per cent, is striking not only because it defies any expectations voiced even a year ago about the fate of the two institutions.

It represents such a complete reversal that one might be tempted, with due licence, to recall the biblical maxim that “the last shall be first.”

Equally remarkable is the speed with which such an alignment — likely to exceed the two-thirds threshold for merger approval when the books reopen — has been forged among shareholder groups who, one must assume or at least hope, share a common vision of this unusual combination.

As of today, the precise contours of that vision remain unclear, since the investor material provided has raised more questions than it has answered.

Yet the very fact that agreement has been reached, in a country where it has always been easier to quarrel than to coalesce, is cause for cautious optimism.

For the sake of the banks involved and the country that hosts them, doubts should now give way to efforts ensuring that future developments vindicate hopeful expectations rather than gloomy fears.

But the hard part begins now. The new coalition of “conquerors” faces three immediate and formidable challenges.

The first is to build credibility in leading a banking project of this scale. None of the main shareholders has a relevant track record.

Worse, at least two elements undermine confidence that such credibility can be swiftly acquired.

The first is the widespread perception that this is a politically driven manoeuvre.

The government has advanced no serious evidence that a tripolar banking system is preferable to a duopoly, assuming one even accepts that the “market” in question is a purely national one. Personal and political sympathies appear to be at play.

The second is that the two driving forces behind the deal — Delfin and Caltagirone — have primarily industrial interests. That raises legitimate fears that adding a banking arm will generate conflicts of interest.

The fact that the transaction is formally bank-on-bank does little to dispel such concerns, given the evident influence these groups have in guiding the hand of Luigi Lovaglio, the able executive who has acted as the operation’s frontman.

The second challenge is to articulate a convincing industrial strategy.

Here the longstanding doubts resurface: how does a retail-focused, essentially domestic lender combine with an investment bank active in entirely different markets? Can two such divergent corporate cultures be fused?

The answer belongs to the future, but it is already clear that the logic of the deal depends on it being a starting point, not an end. In today’s Europe, the universal banking model — with all its flaws — still prevails, not only for the synergies it generates but also because it diversifies revenues and stabilises returns.

Moving in this direction requires reinforcing and expanding the retail base while combining it with strong positions in asset management, insurance, and pensions.

The oft-rumoured expansion towards Generali may yet prove to be the only way to give this merger coherence — and to provide the European and global horizon that alone now matters.

Finally, the third challenge, intertwined with the other two, is to develop a constructive dialogue with regulators, above all, the ECB.

Frankfurt has been criticised in some quarters for approving the takeover — wrongly, in my view. But in approving it, it also signalled that it expects clarity on governance and strategy within six months of completion. The clock is already ticking.

The first critical test will come with the appointment of new directors and management at Mediobanca’s shareholder meeting on October 28.

Choosing a strong and independent slate would send exactly the kind of signal that could decisively shape the next phases of this saga. Here, another maxim comes to mind — less august than the biblical one, but no less apt: you only get one chance to make a first impression.

A previous version of this article was published by Milano Finanza

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.