1985: Sign of the Times

At the June 1985 European Council meeting, in Milan, the diverging views about the future of Europe – its identity as a common trading area or as a more cohesive bloc – were bound to clash strongly, given the fact that the meeting was intended to consider various proposals for the reform of the European institutions. A paper by Andrea Colli

-

FileColli WP_IEP-annualevent_final.pdf (251.48 KB)

Executive Summary

The European Council meeting in Milan at the end of June 1985 can be better understood by examining the perspectives of the then Italian political leadership on Italy's global standing and its role within the emerging European Union, as well as the European leadership's vision of Europe's present and future identity.

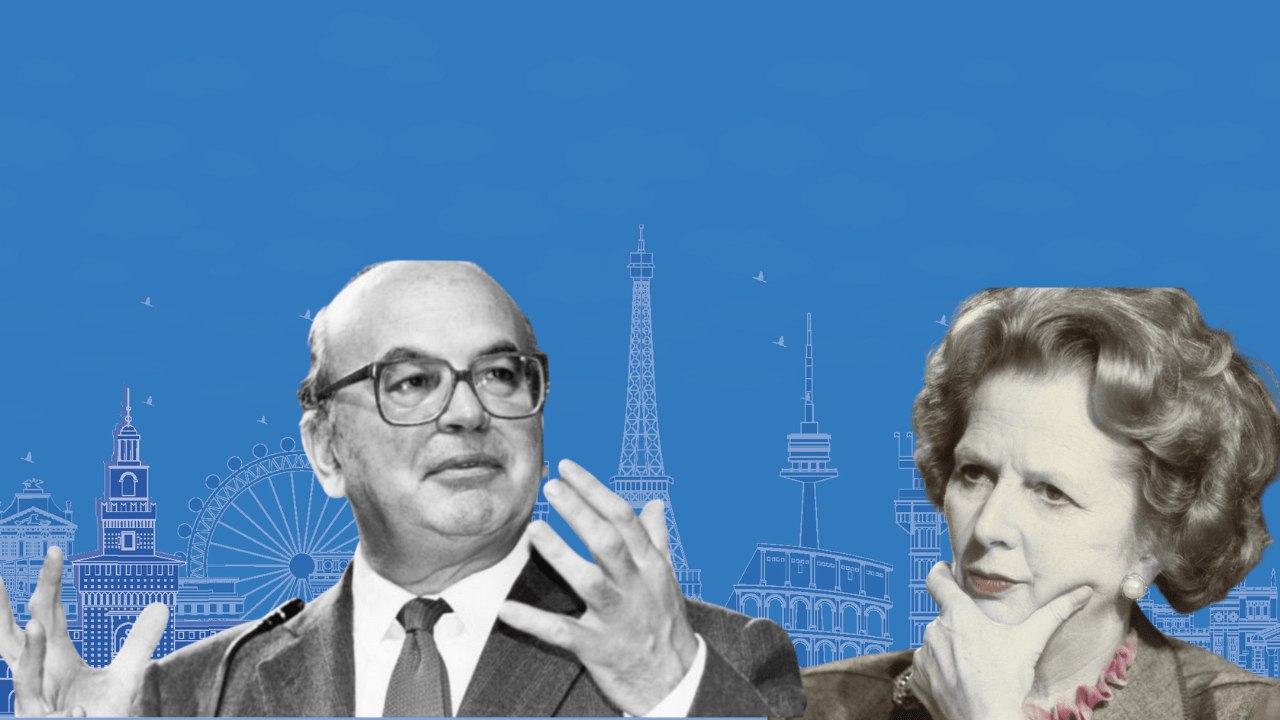

Prime Minister Bettino Craxi, a socialist leader, used this opportunity to articulate his views on Italy's global role and its place within the European Community (EC). He advocated for strengthening Europe as a political entity, rather than merely an economic partnership. Craxi's outlook aligned with that of the governing coalition's "Atlanticist" vision, which emphasized cohesion among European countries and the United States through NATO treaties.

At the time, Italy was enjoying economic prosperity. Its GDP per capita was similar to that of the United Kingdom and just slightly below that of France and Germany.

The country had successfully reduced inflation from a peak of 21% in 1980 to just over 4% by the mid-1980s. The trade deficit was diminishing, thanks to the success of "Made in Italy" products from industrial districts. While public debt was rising, it remained manageable and had not yet reached the alarming levels seen in the early 1990s. Italy’s reputation had dramatically improved, both globally and among European partners.

The meeting was characterized by tension, primarily due to resistance from some members, notably the United Kingdom, which had historically opposed transforming the trading area into a more integrated political and economic union. For that to occur, an Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) was necessary.

Even if the European Council was not required to achieve full unanimity in its decisions according to the provisions of the Rome Treaties, consensus had so far been the rule.

However, in order to break the deadlock and proceed with organizing an IGC, the Italian Presidency took the unusual (and unexpected) step of proposing, for the first time, a majority vote on the matter. The ability to leverage a majority vote under Article 236 of the Rome Treaty facilitated progress, despite the frustration of a characteristically Euro-skeptical Margaret Thatcher about holding an IGC. This was a fundamental move towards the Single European Act and, ultimately, the new European Treaties signed years later in Maastricht in 1992.

The IGC would indeed take place on September 9, 1985, with the support of seven of the ten member states.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.