Where Europe Stands Tall: The Lesson of Aerospace in a World of US Tariffs

Europe’s exemption from US tariffs in aerospace highlights what the continent lacks elsewhere: unity, scale, and strategy. A commentary by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi.

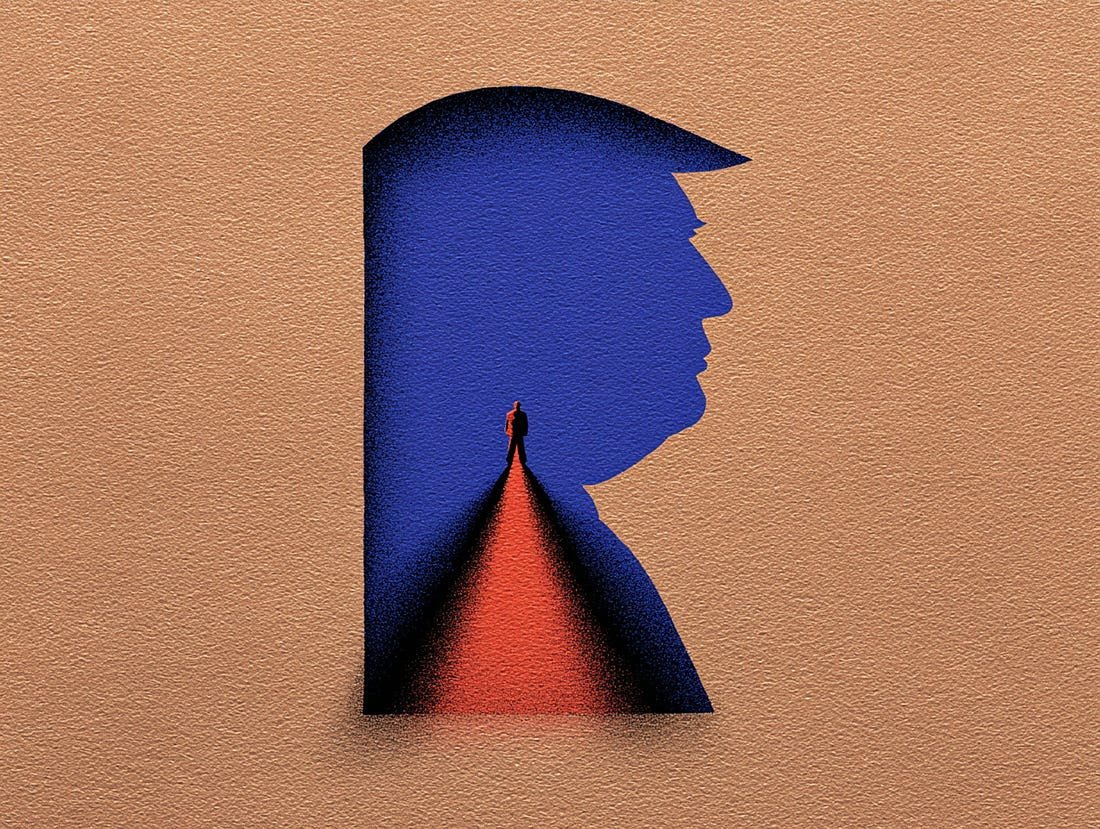

The televised handshake between European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and US President Donald Trump, celebrating their newly announced trade agreement, was hard to swallow.

It followed a series of concessions made to Trump over the past six months—from military spending to the taxation of multinationals—each carrying a financial and economic cost for Europe. And it all occurred without any effort to push back, for example, in the services sector, where the US enjoys a net export advantage.

At this point, it is of little use to argue whether the responsibility for the outcome lies with the European Commission or the governments of member states.

The familiar European ritual of blame-shifting is alive and well: bad news is always the fault of the “bureaucrats in Brussels.”

Yet it is conveniently forgotten that those bureaucrats were not present at the NATO negotiating table when European countries agreed to increase military spending, nor at the G7, when American multinationals were exempted from minimum taxation.

Perhaps it is more useful to ask why it ended up this way—if only to avoid repeating the same mistakes in the future.

The aerospace sector, the only industry spared from US tariffs, is an interesting starting point.

This was no oversight by Trump.

Aerospace is virtually the only sector where Europe possesses genuine strategic autonomy.

Not only does Europe have global players—Airbus, Leonardo, Saab, Dassault, Safran—that produce worldwide and can compete on equal terms with US giants like Boeing or General Electric; Europe also supplies crucial components for American manufacturers. Trump could not afford to wage a trade war with Europe in aerospace, and so he did not.

The problem is that no other European industry enjoys a comparable level of autonomy or negotiating power vis-à-vis the United States.

In technology—a sector where the US is a net exporter—Europe simply does not have companies capable of competing with or substituting for their American counterparts.

There are currently no credible alternatives to products from the so-called “Magnificent Seven”: Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Tesla, Meta, Nvidia, and Facebook. Taxing them ultimately means taxing European consumers.

In finance, the dominant position of American companies in every segment—from investment banking to asset management, from private equity to credit rating agencies—makes them virtually indispensable. When a major strategic investment must be planned, no European financial institution has the balance sheet to go it alone.

This state of dependence on American companies is not accidental. It is the result of deliberate choices by European governments and institutions, which have failed to support—or have actively hindered—the creation of globally competitive firms.

On the one hand, national governments continue to veto cross-border alliances, mergers, or joint ventures that could create true European champions in key sectors such as telecoms, energy, and finance. They prefer to retain political control over domestic companies, even when those companies are far too small to matter on the global stage.

On the other hand, European regulation—especially on competition policy and state aid—is based on principles that no longer reflect the realities of the global market. It has not been understood that whenever these rules put European firms at a disadvantage internationally, the rules themselves become irrelevant.

Both the US and China have grasped that their sovereignty is closely tied to their ability to avoid depending on one another, especially in finance and technology. Their economic policies are now squarely focused on this fundamental goal.

In Europe, it is still unclear to many that there can be no sovereignty as long as we depend on decisions made in the United States or China. The aerospace industry should serve as an example of how Europe can reduce its dependence and avoid having to suffer the consequences of choices made elsewhere. This, however, requires a change of pace—both in Brussels and in the 27 European capitals (or at least the most important ones).

Contrary to Trump’s claims, Europe was not created to “skrew” the United States, but rather to ensure the opposite did not occur. We have not fully succeeded— as yet.

A first version of this article was published in the Italian daily Il Foglio

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.