Is the EU Strategic Autonomy Consistent with Development Goals?

We identify specific industrial products that are projected to be in high demand in the EU and can be realistically produced given North African countries’ existing capabilities. Specializing in these products, North African countries can diversify their export basket, which has been shown to correlate positively with economic development.

The new geo-political context emerging after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, coupled with the need to manage the green and digital transitions, is having an impact on the overall framework of EU policies.

These are increasingly centered on the idea of ‘strategic autonomy’, that is the capacity of the EU to act autonomously, without being dependent on other countries, in key strategic areas ranging from defence policy to industrial policy.

In this context, on 1 February 2023, the European Commission presented “A Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age”, a plan designed to respond to the US Inflation Reduction Act (and related subsidies), by supporting the scaling up of manufacturing capacities for EU net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.

Central to the plan is the idea of reducing EU foreign dependence on key imported raw materials and intermediate goods. In particular, the plan articulates a “Net-Zero Industry Act” (NZIA) which identifies key technologies and products (among which batteries, heat pumps, solar, electrolysers, windmills) to boost in terms of internal production, and for which it will be required to manage dependency risk.

In parallel, the EU has launched a “Critical Raw Materials Act” (CRMA), which aims to make the EU more self-reliant in mining, processing and recycling a list of 34 critical metals and minerals, by accelerating and financing national programs for exploring EU internal geological resources, as well as limiting the sourcing of critical minerals from third countries by 2030.

The critical raw materials are part of a broader set of 137 primary and processed products for which “the EU can be considered highly dependent on imports from third countries”.

While the new “strategic autonomy” focus is clear in the new policies, its actual achievement presents important challenges.

Within the EU, issues arise on whether this more inward-looking restructuring of the European production processes is feasible, let alone efficient. In other words, one has to ask to what extent the EU will be able to substitute international inputs with domestic, or better, “strategically autonomous” ones, while maintaining a competitive production and exporting capacity of final goods and services.

Outside of the EU, the question arises on the consequences that an inward-looking restructuring of EU value chains might have for the development of third countries, especially in terms of their ability to reach SDG9 goals, which are related to the build-up of a sustainable industrialization process, supported by resilient infrastructures and adequate rates of innovation.

Egypt could specialize in certain chemical compounds for which EU demand grew by more than 10% over the five years preceding the pandemic

The question is particularly relevant for North African countries (NACs) and developing countries in general, in light of their high level of trade integration with the EU, combined with the critical specialization of some of their exports, often focused on agriculture or energy-related products.

Furthermore, strategic autonomy should be reconciled with the principles of the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), launched in 2003 and aimed at fostering economic diversification and deepen integration with non-EU neighboring regions.

A recent Communication updates the ENP framework in light of COVID-related developments:

“… the focus on open strategic autonomy and the restructuring of global value chains in the wake of the pandemic has the potential to create new opportunities for further integrating industrial supply chains between the EU and its Southern Neighbours … contribute to diversification efforts and to the development of win-win initiatives in the areas of market integration …”

“industrial clusters within the Southern Neighbourhood could help economic development by connecting businesses to global and regional value chains, reducing the isolation of SMEs, promoting innovation, and generating more trade and investment.”

Changing the status quo and achieving a stronger diversification of NACs’ export basket requires identifying high-value-added industrial products that can be, on the one hand, realistically produced given their resources and capabilities. On the other hand, these products should be consistent at the same time with the strategic objective of the EU.

Diversifying into the right products would increase North African countries’ development prospects and reduce their vulnerability to market fluctuations

Diving into diversification

In a new policy brief in collaboration with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), we identify specific industrial products that are projected to be in high demand in the EU and can be realistically produced given NACs’ existing capabilities.

Specializing in these products, NACs can diversify their export basket, which has been shown to correlate positively with economic development.

Our methodology builds on UNIDO’s DIVE (Diversifying Industries and Value Chains for Exports) tool, which based on product-level international trade data identifies products that are not currently produced by a country but are nonetheless successfully produced by countries at a similar level of economic development.

We combine DIVE with a novel filtering procedure imposing three further restrictions on the products: i) strong expected EU demand; ii) large value added generated in production, and iii) a revealed comparative advantage.

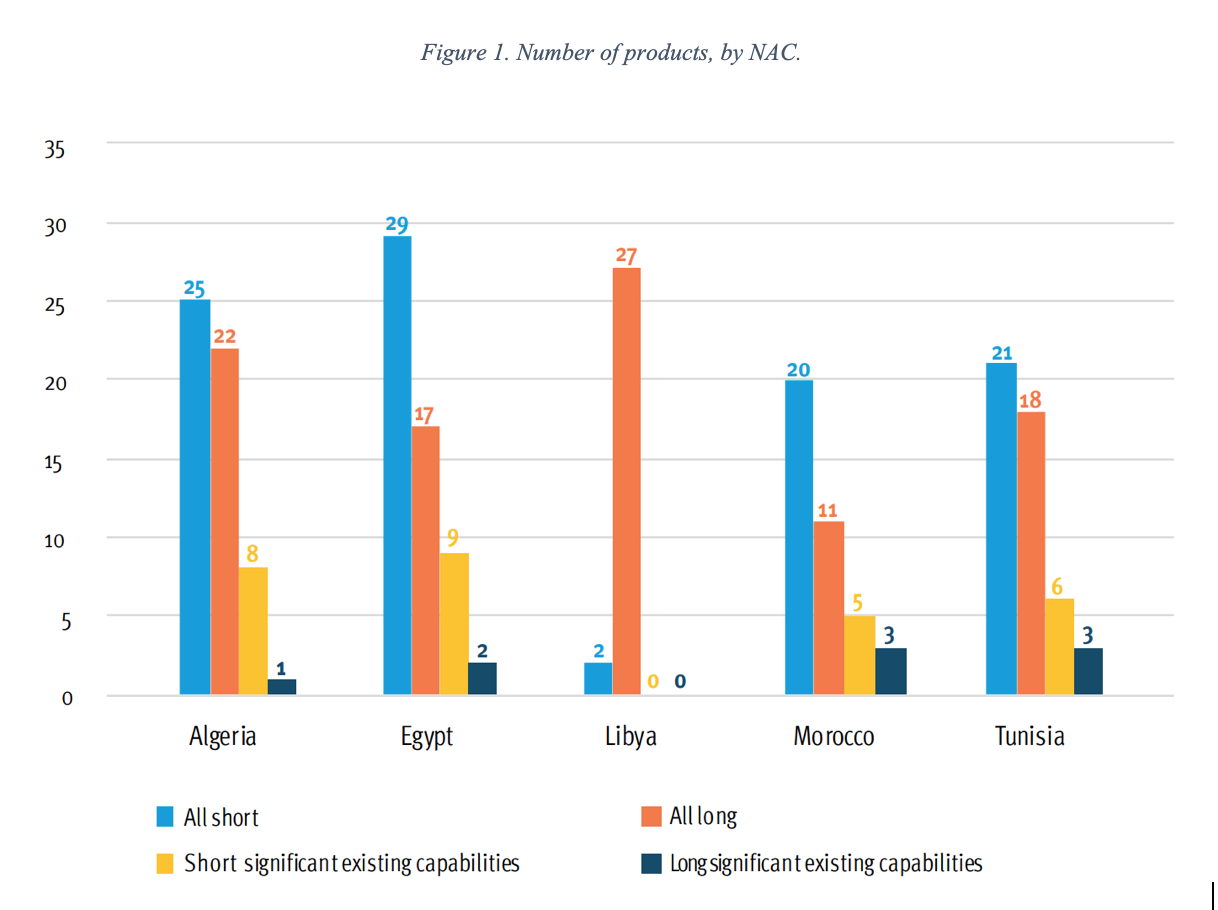

Figure 1 summarizes NACs’ opportunities in terms of the number of products identified with our approach. These opportunities are distributed across different industrial sectors and vary in terms of ambition.

This is reflected in the distinction between relatively easy and ambitious specialization – respectively deemed “short” and “long jumps” in the DIVE taxonomy.

For instance, Egypt could specialize in certain chemical compounds for which EU demand grew by more than 10% over the five years preceding the pandemic. These chemicals include compounds such as saccharin, as well as products for therapeutic use.

The fact that Egypt already exports similar chemical products suggests that it already possess some of the necessary conditions for further specialization – such as skilled workers, suppliers and suitable distribution networks – thus making it an example of easy diversification.

An example of long jump – a more ambitious but potentially more rewarding diversification goal – would be Libya specializing in certain textile products, such as fabrics processed in different ways and from different materials, or metal products such as frames or ornamental objects.

Although EU demand for such products has grown over the years, Libya’s current export basket is highly concentrated on petroleum, making it unlikely that the country possesses all the capabilities required for diversification.

Policy Options

Multiple crises and the weakening of global value chains may slow down the industrialization path and the EU effort to promote manufacturing development (incarnated in SDG9) in NACs. A strict pursuit of “strategic autonomy” by the EU, irrespective of the existing commitments within the European Neighborhood Policy, risks undermining decades of market integration in the area. This would damage developing and advanced economies alike.

Diversifying into the right products would not only increase NAC’s development prospects and reduce their vulnerability to market fluctuations but would also align their trajectory with the EU’s new strategic policy orientation.

By leveraging NACs’ comparative advantage in the production of strategic goods, the EU could also benefit from enhanced market integration, especially within the middle-end of the value chain. This, in turn, could lead to a more efficient allocation of resources and greater productivity.

The key obstacle to enhanced integration between the EU and NACs is the lack of appropriate production capabilities.

One policy option to that extent is the Global Gateway framework initiative, launched in 2021 as the new EU tool of trade policy, technical assistance, capacity building, and development cooperation. Extending the EU financing initiatives to NACs along the lines discussed in this commentary would be key in facilitating their industrial development and integration with the EU single market.

This commentary is based on the UNIDO Policy Brief Diving into diversification: How North African countries can boost economic ties with the EU, co-authored by Carlo Altomonte, Nicola Cantore, Nicola Coniglio, Cristiano Pasini, Giorgio Presidente and Davide Vorchio.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.