EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the Global South: How to Make it Work

If the EU (and other rich countries) is genuinely interested in tackling climate change, it has to ensure that adequate funding is available for adaptation and loss and damage. It can then justifiably expect all countries to pitch in with mitigation.

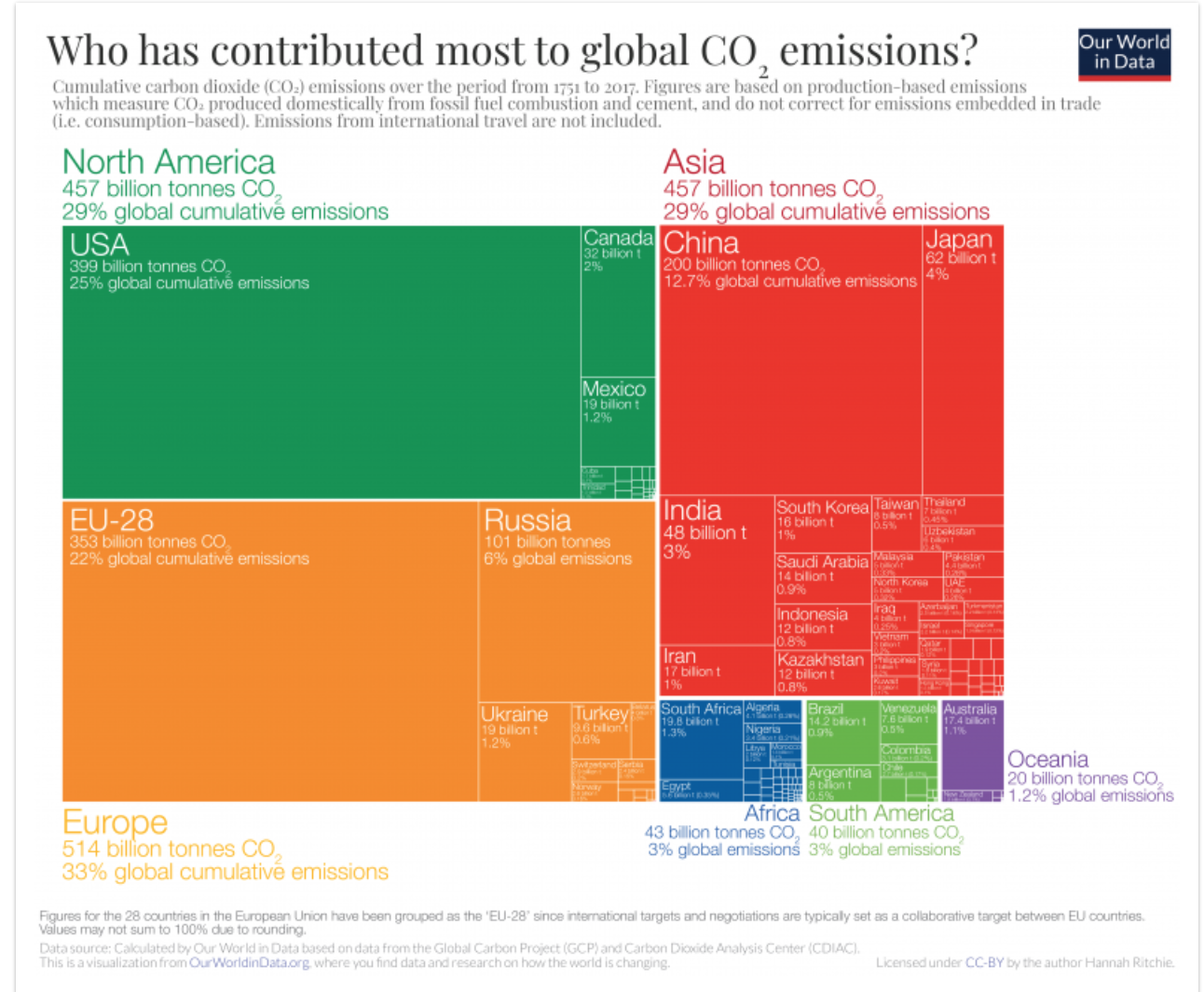

Climate change is primarily caused by the accumulated carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The main cause of this is the burning of fossil fuels. No matter where the fossil fuel is burnt, carbon ends up in the atmosphere. Thus, it has a public good (or, rather a public bad) nature. Since it is the stock of carbon dioxide that matters, the responsibility for this lies in the dirty industrialization process of the advanced economies.

It is important to remember that the problem is both transboundary and inter-temporal. I mention this explicitly since the latter is routinely ignored in international trade models dealing with this problem since these are static models.

The US’s cumulative emissions are responsible for twenty-five percent of the carbon in the atmosphere, the European Union (EU) for about twenty-two percent. The contribution of the poorer countries (the Global South) is negligible. Even China’s share of 12.7 percent—on a per capita basis is significantly lower than the US and the EU. (These figures cover the period 1751 to 2017. They are taken from “Our World in Data”.)

The Kyoto Protocol recognized this and asked for “common but differentiated responsibilities” in the fight against climate change. Its successor, the Paris Agreement, required countries to set voluntary emission targets but asked (under the Copenhagen Agreement in 2009) the richer countries to make financial transfers to the developing economies for the latter to cope (i.e., to reduce emissions and adapt to the negative effects of climate change) with the problem. It set a floor of USD 100 billion per year. This was supposed to be over and above 0.7 percent of their national income which was their overseas development aid.

The definition of ‘climate finance’ is a contentious issue e.g. should non-concessional loans be counted? Poorer countries (we shall refer to them collectively as the Global South) were already under immense pressure in servicing their external debt; something that was exacerbated by Covid-19. To pile climate change borrowing on top of this is unconscionable.

In 2020, USD 83 billion was paid into climate finance, of which less than USD 25 billion was in the form of grants. Thus, there is a shortfall in the amount that industrialized countries were supposed to contribute, as well as in its composition.

The CBAM is asking countries with very different technologies to face the same price of carbon. The more antiquated the technology, the lower will be the output, perpetuating historical inequalities

How CBAM is Supposed to Work

The EU has embarked on an aggressive path of decarbonization. It hopes to reduce its emissions by 55 percent between 1990 and 2030. Its emissions have already fallen by about 30 percent, aided by its ETS scheme.

The ETS (Emissions Trading System) is a “cap and trade” scheme: “cap” refers to an overall limit to carbon dioxide that the EU permits; “trade” refers to permits that can be bought and sold by firms whose production activity will cause carbon dioxide emissions.

Carbon embodied in imports constitutes about 20 percent of the EU’s total emissions. To reduce the imported emissions, it has put forward a proposal called the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Other countries e.g. the US, Canada, and Japan are planning similar measures.

The CBAM involves imposing tariffs on imports from countries that do not “price” carbon appropriately, and hence, use carbon-intensive methods of production. All imports to the EU will be subject to this test. In this essay, we are concerned with only the developing countries facing the CBAM.

It is expected that the tariff on these goods would restore competitive parity to the EU’s domestically produced goods, which are subject to a higher price of carbon. Currently, the EU gives free allowances to its firms to tackle this loss of competitiveness. These allowances would be phased out as the CBAM comes into effect in 2026.

Such a tariff under the CBAM will achieve three objectives: first, to reduce EU emissions; second, to restore competitiveness for the EU in carbon-intensive goods i.e. to plug “carbon leakages”; and third, to make the targeted countries reduce the carbon intensity of their exports.

The CBAM will cover six product categories viz. cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilizer, hydrogen, and electricity generation. The countries most affected will be Russia, Ukraine, Turkey, India and China. Only three of the 12 top exporters to the EU, have a mechanism for “pricing carbon”.

There are some issues that the CBAM needs to address in its design. First, which countries are covered? These are those that possibly do not have a national emissions (or a sectoral) cap; the poorest countries could also be exempted. Second, which emissions are included for the levying of the import tax? Are indirect emissions embodied in inputs like machines to be considered, or only direct emissions? Finally, which products are to be included? Possibly, a narrow coverage with high trade and carbon exposure. While currently only six products are included in its ambit, it is planned to extend the CBAM to cover other goods by 2034. Note that these six products covered are intermediate inputs, evidently chosen for easier identification of their carbon content.

What does international law say about this? From the beginning, GATT (and its current avatar the WTO) has promoted free trade to prevent the world from slipping back into the anarchy of the inter-war period (marked by protectionism, competitive devaluations, etc.).

The CBAM is a unilateral move, against the spirit of multilateralism. The problems of measurement mean that it could be used for protectionism. Moreover, it targets production processes (and not the product itself) that the WTO hitherto has not approved of.

It is very demanding in terms of paperwork, which could act as a non-tariff barrier. The data requirements about production processes demand information that the firms may be reluctant to share.

Can the WTO accommodate the CBAM? One can easily find many examples where they would be in conflict. To use the existing rules, a consensus or, at least a majority among WTO members is required.

A reform of the WTO is unlikely, but bypassing it would lead to retaliations and trade wars. During the recent December 2023 COP 28 meeting, the WTO Secretary General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala spoke positively about green policies. It remains to be seen whether the WTO, as an organization, will embrace this. And how quickly.

If the EU is genuinely interested in tackling climate change, it has to ensure that adequate funding is available for adaptation and loss and damage

The Global South Perspective

How does the CBAM package fare from the perspective of a developing country whose exports are going to be affected?

If the proposals are meant to reduce carbon emissions of the EU and restore competitiveness to the industries in the EU, and if the problems of measurement and WTO compatibility are addressed, then the proposal meets its objectives. It has certainly led many developing countries to scurry to try and get a carbon trading system in place to meet (even if partially) the EU’s requirements.

Once the Global South is expected to co-operate, some uncomfortable questions arise.

One cannot wave history aside by saying, “Let bygones be bygones”. History is very much present in the form of the development needs of poor countries. Besides climate concerns, education, health, and physical infrastructure require funding. Given the tardy flows from the richer countries both under the heads of ODA (Official Development Assistance) and climate finance, developing countries have to rely on their own resources.

For these countries, even under the rubric of climate-related expenditure, of the three heads –mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage— it is not at all clear that mitigation is the first claimant. As mentioned earlier, economies of the Global South did not contribute to the problem of the stock of CO2 in the atmosphere but have to allow for adaptation and loss and damage (including these makes $100 billion a year small change).

A proposal like CBAM is targeting mitigation alone. Poor countries are being asked to limit additions to the stock of carbon from now on. This is without any significant financial transfers, or, more importantly, in this case, a transfer of technology.

The CBAM, in effect, is asking countries with very different technologies to face the same price of carbon. The more antiquated the technology, the lower will be the output, perpetuating historical inequalities. Leave aside the transfer based on the historical carbon profligacy of the rich countries, it is unlikely the tariff revenue generated by the CBAM will be rebated to the developing countries.

Climate change is a problem that faces the human race. It has to be confronted in a cooperative manner, involving all the parties. To get so many different players to co-operate is no mean task. Given the nature of climate as a public good, free riding is to be expected. But the CBAM proposals with only sticks for the “recalcitrant” players flies in the face of equity. If the EU (and other rich countries) is genuinely interested in tackling climate change, it has to ensure that adequate funding is available for adaptation and loss and damage. It can then justifiably expect all countries to pitch in with mitigation.

In passing, my understanding of a free-rider is one who is not contributing, although has the means to do so. The country that fits this definition is the United States, with its “sometimes in, sometimes out” response to climate action. The developing countries did not create the problem, and have limited means to pay for a “clean up”.

Although strictly speaking the CBAM proposal is designed to prevent carbon leakages in the EU’s bid to achieve its target of reducing emissions by 55 percent, it is often projected as “fighting climate change”.

If we go from its partial equilibrium confines to a general equilibrium setting, it is easy to point out some other imponderables in the way.

First, it targets only carbon-intensive imports into the EU, and, thus it affects only a small fraction of global emissions. Second, the affected countries could retaliate by imposing tariffs and/or non-tariff barriers. Third, a piecemeal reduction in fossil fuel fuel use could have perverse reactions from oil-producing countries.

Faced with their resource becoming “stranded” (now, or in the future) they could pump out oil today (as long as extraction costs are lower than the market price)—this is known in the literature as “the Green Paradox”.

Climate Change poses an existential problem for the whole world. Since carbon emissions have a public good nature, it has to be confronted in a cooperative way by the whole world. However it is important not to overlook equity considerations in devising these policies.

A transfer of funds and technology to the countries of the Global South (who did not create the climate problem, in the first place) would help elicit such co-operation.

A lack of co-operation would spell disaster in the fight against climate change; in the immediate future, it could seriously affect the international trading regime that has been put in place since the Second World War.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.