Generative AI and the rediscovery of the legitimate interest clause

The proliferation of advanced generative AI models has unequivocally highlighted what was already foreseeable since the advent of the algorithmic era. The traditional notion of "consent" is no longer a viable proposition in the context of an algorithmic society. Given the increasing sophistication of emerging AI generative models, which legal basis could be a reasonable alternative?

When data protection law was introduced in Europe back in 1995, before the explosion of the digital era, there was hope that the golden rule of obtaining the “needed consent” from data subjects would grant them complete control over their personal data.

However, as society transitioned from the physical realm to the digital world and the algorithmic society took shape, this ideal became more of an illusion, akin to a fairy tale.

The belief in the effectiveness of consent as a substantial safeguard for control over personal data has vanished.

With the exponential growth of generated data and the increasing computational power driving the development of conventional AI (distinguished from "generative" AI), the role of consent as a significant control safeguard has diminished, giving way to a mere formalistic label that often fails to effectively protect data subjects.

However, a rediscovery of the clause of “legitimate interest” might prove a reasonable legal basis in the generative AI era.

OpenAI limitations in Italy

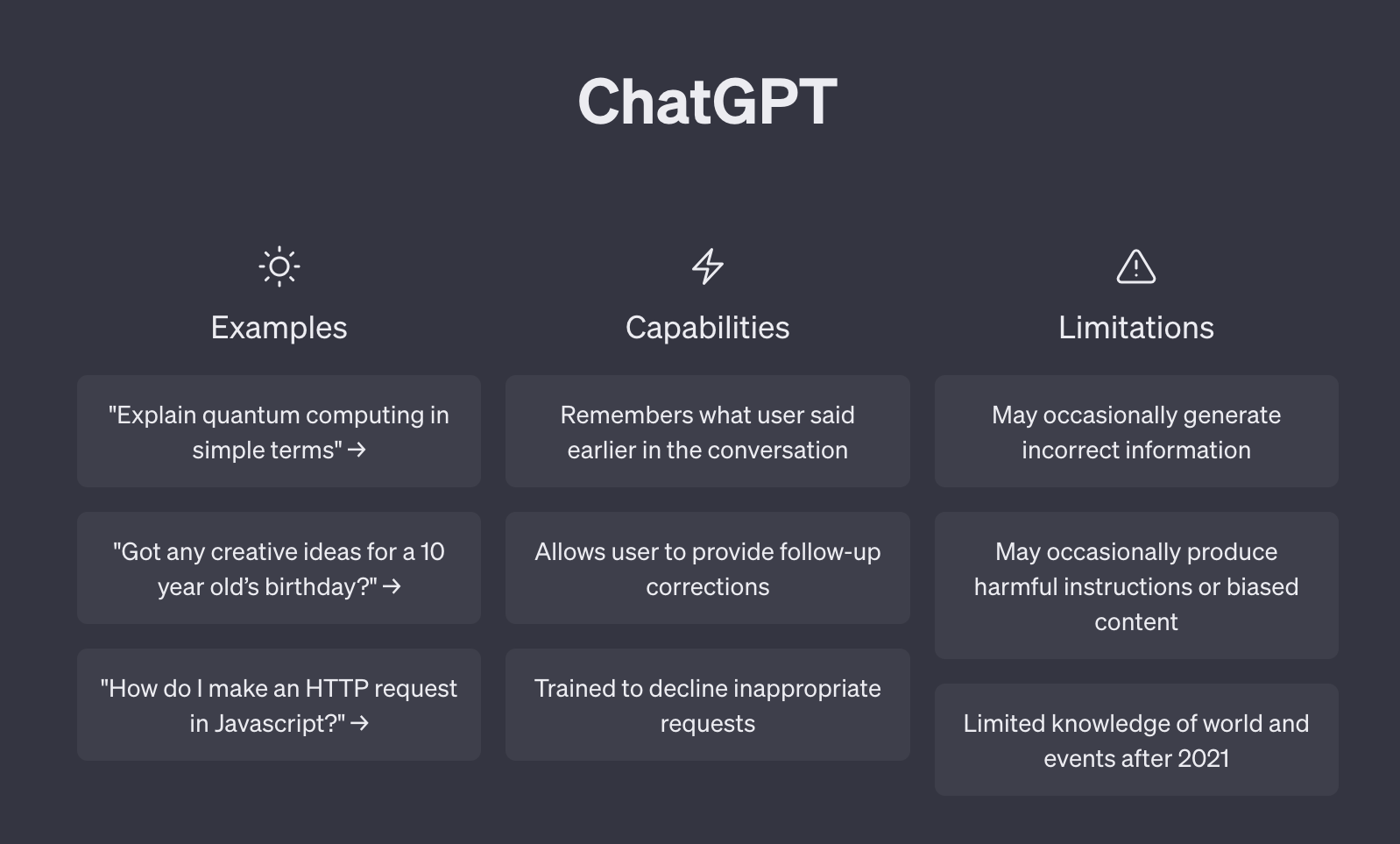

The Italian ChatGPT saga provides a relevant case study to support the proposed alternative approach. The Italian authority for the protection of personal data (known as the “Garante”) took an emergency measure on March 30, 2023. The emergency measure was enacted by Pasquale Stanzione, the president of the Italian data protection authority, in response to the reported breach that had occurred ten days prior. The order disposed that the company OpenAI LLC immediately stop processing personal data of Italian users2.

In response, OpenAI barred access to its chatbot in Italy. The Garante argued that OpenAI was using personal data of its users without their consent, alleging thus a breach of the European rules on data protection, as enshrined in European data protection rules, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Another issue raised by the Italian Garante was the absence of any age-related filter, thus allowing minors (below 13 years) to access the chatbot and to potentially have access to inappropriate content.

The observation that the OpenAI chatbot does not have a separate age filter is formally correct, but it disregards the reality that most users access ChatGPT via their Google or MS accounts, which do have age restrictions.

The temporary ban offers some important lessons about the proportionality and effectiveness of bans on developing technologies, about coordination between member states at the European level, and how to balance access to services with the need to protect children from accessing harmful content.

In a different order, issued in April, 11, 2023, signed by all the Garante members, the Italian data protection Authority asked OpenAI, among other things, to “change the legal basis of the processing of users’ personal data for the purpose of algorithmic training, by removing any reference to contract and relying on consent or legitimate interest as legal bases by having regard to the assessment the Company is required to make from an accountability perspective”.

OpenAI communicated to Garante the measures it implemented to comply with the 11 April order. The company explained that it had expanded the information to European users and non-users,; also, it had amended and clarified several mechanisms and deployed amenable solutions to enable users and non-users to exercise their rights. As a result of these efforts, ChatGPT has once again become available for Italian users.

The Italian ChatGPT incident highlighted an important aspect of data privacy concerning the training of models using publicly available personal data. As the training model utilizes data from the entire internet, it inevitably includes publicly accessible personal data.

For instance, authors' CVs on institutional websites and personal websites containing significant personal information may be part of the training dataset. Obtaining explicit consent from each individual for the use of such data in training the model would be practically impossible for OpenAI. This is a plastic example of the sunset of consent as a substantial safeguard for the data subject.

An alternative to legitimize the use of public personal data would be the legal concept of “legitimate interest”, which was mentioned by the Italian Garante as a possible legal basis in mentioned decision adopted on April 11.

The Italian data protection Authority asked OpenAI, among other things, to “change the legal basis of the processing of users’ personal data for the purpose of algorithmic training, by removing any reference to contract and relying on consent or legitimate interest as legal bases"

The rediscovery of legitimate interest

The re(discovery) of the legitimate interest promises a more realistic legal basis for the use of personal data by generative large language models.

Legitimate interest is not a new concept. It was already present in the 1995 EU directive o and the 2016 GDPR, Article 6, clearly states that besides consent and other legal basis, meaning on an equal foot, processing shall be lawful : If necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data, in particular where the data subject is a minor.

If, however in the 1995 Mother Directive legitimate interest was, in terms of legal basis, only an exception to the golden rule of consent, by contrast, according to GDPR, the two legal basis are now on a equal foot. Which is the reason of such choice?

After more than 20 years became clear, with the adoption of GDPR, that protection of data goes hand in hand with need to ensure the circulation of the same data, within and outside European Union. In order to achieve this goal the GDPR added value is the focus on the responsabilization and accountability of the data controller.

The legitimate interest clause, as described above, is the concretization of the accountability principle. The person or legal entity who is taking the decision related to the aims of data processing can choose to not ask the consent in certain cases. More precisely, when, as mentioned, the activity to be carried out is necessary for the purposes of the controller.

But, in order to not be sanctioned by the Data Protection Authority, the same controller is supposed to assess the right balancing test between the need to pursue his economic goals and the necessity to protect the interest or the fundamental and freedoms of the data subject.

Not an easy task.

By referring to legitimate interest, the Italian “Garante” acknowledged the possibility that OpenAI would be entitled, after having carried out the balancing test identified above, to process the type of personal data described above (which are allergic to be processed under the consent rule) using as legitimate interest as legal basis.

Within this context this clause, until recently formally available but substantially neglected, now emerges as the legal solution that might reconcile the need to protect privacy with the (often) conflicting need to ensure the functioning of digital markets without hampering innovation.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.