Monetary Policy in the COVID Era and Beyond: the FED vs the ECB

Federal Reserve monetary policy has been more expansionary than the one predicted by the rule until the second quarter of 2022, then this tendency was reversed. The evidence is very different for the case of the Euro area, where the observed policy rates are consistently below those predicted by the model and fluctuate outside the range compatible with the model-related uncertainty.

The unprecedented nature of the COVID era, coupled with the subsequent rise in inflation, has prompted a reevaluation of global central banks' monetary policy decisions around the world.

Notably, there is a marked contrast in the timing and intensity of monetary policies between the Federal Reserve (FED) and the European Central Bank (ECB). This has sparked discussions on the suitability of these varied strategies for their respective economic contexts.

In principle, the distinct actions of the FED and the ECB can be attributed to the different shocks influencing inflation in the US and the Eurozone. In the former, the dominant impetus behind post-COVID inflation has been mainly attributed to a resounding demand shock, epitomized by the expansive fiscal response following the initial COVID shock.

Meanwhile, the European inflation narrative unfolds mainly as a manifestation of supply shocks—orchestrated by the interplay of supply chain disruptions stemming from sporadic lockdowns during the pandemic and the amplification of energy costs due to geopolitical tensions such as the Ukraine conflict.

However, some commentators (Gros 2023) have argued that central banks played a significant role in causing the surge in prices. This surge is attributed to the delayed impact of the excessive expansionary monetary policy during the pandemic.

In a recent paper, Favero and Fernandez-Fuertes(2023), provide empirical evidence relevant to this debate by assessing how monetary policy rules specified and estimated on the pre-COVID data do in explaining out-of sample, in the COVID era and beyond, the behaviour of the FED and the ECB, conditional on the shocks they were confronted with.

The rules are specified by determining monetary policy rates in a model where the drift in rates depends on productivity, demographics and the inflation target of the central bank and monetary policy controls fluctuations around the trend by responding to stationary cyclical variables, such as the difference between the level of output and its potential level and the gap between current inflation and the survey-based forecast for long-term expected inflation.

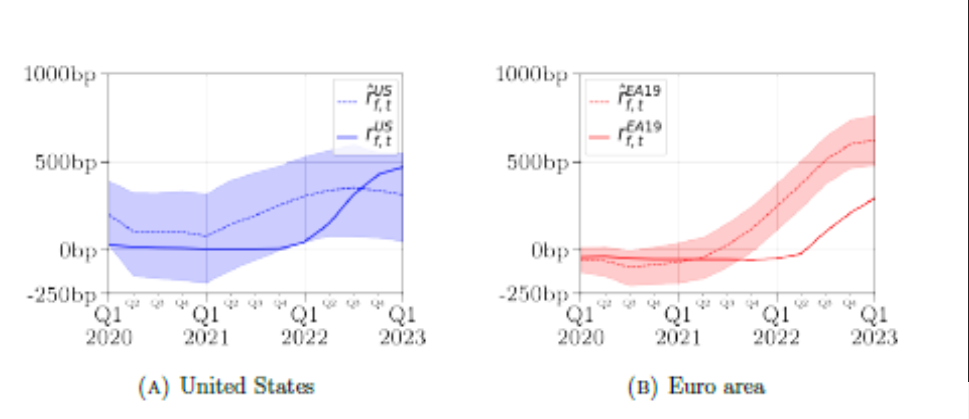

Figure 1 allows us to compare actual and model-predicted data for the Fed and the ECB. The evidence shows that in the case of the FED monetary policy has been more expansionary than the one predicted by the rule until the second quarter of 2022, then this tendency was reversed.

Figure 1 Simulation of three-month interest rates for the US and the Euro area the after COVID era (2020 Q1-2023 Q1). Coloured band is the confidence interval at the 95% level

However, the actual monetary policy rate has been always fluctuating in a range that does not reject the model as a valid representation of the data.

The evidence is very different for the case of the Euro area, where the observed policy rates are consistently below those predicted by the model and fluctuate outside the range compatible with the model-related uncertainty.

The results of the simulations call for an evaluation of alternative specifications for the rule determining the cycle of three-month rates in the euro area.

Bond Fragmentation Risk or Inertia?

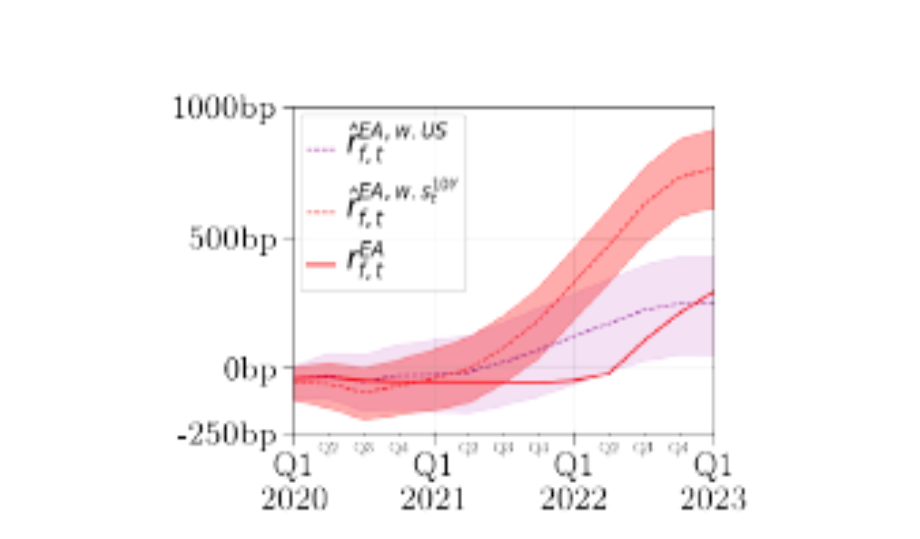

We consider two alternative specifications: the first one is driven by the possibility of an institutional concern for bond market fragmentation in the euro area, that has been expressed in institutional speeches and has led to the establishment of the so called Transmission Protection Instrument, the second one is generated by the view, put forward by commentators in the past , that the central bank in Europe, run by a committee which is too timid and too inertial to anything in time, follows the US example with caution and delay.

The simulation evidence reported in Figure 2 shows that, while the inclusion of a proxy for bond market fragmentation among the drivers of monetary policy does not help to close the gap between actual and model-based data, much better results are obtained by the specification in which the ECB is following the FED with caution and delay.

Figure 2 Simulation of three-month interest rates for the Euro area the after COVID era (2020 Q1-2023 Q1) using a model that allows for a concern for bond market fragmentation (r EA,w,S ) and a model in which the ECB follows the FED with caution and delay(r EA,w,US )

Overall, the empirical results indicate that in the US case simulation of the traditional model conditional on the observed shocks to the output and the inflation gap show an overall robustness of the rule, with monetary policy modestly lagging initially behind the predicted one, to make up for the lost ground in the final part of the simulation.

The results are different for the case of the euro area, where out-of-sample simulations reveal that actual data are persistently outside the 95 per confidence intervals from the simulation model.

Intriguingly, augmenting the traditional rule with variables addressing ECB concerns over bond market fragmentation does not rectify the shortcoming.

Instead, the most effective rule, validated within and beyond the sample, is one where the euro area's cyclical rate components slowly and cautiously align with the US cycle.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.