The "national security argument" for new US protectionism

American protectionism has been reinvented in the name of “national security”. Yet, the belief that a country can achieve its own “nationally security” unilaterally is debatable.

American protectionism has been reinvented in the name of “national security”. Yet, the belief that a country can achieve its own “nationally security” unilaterally is debatable.

When Donald Trump became President of the United States (POTUS) in 2016, his electoral slogan “Make America Great Again” was immediately rendered as “America First”, taking up the motto of the American administrations (both Democratic and Republican) that between the two World Wars had pursued an attitude of neutrality with respect to European events.

During Trump’s presidency America First became the label of an isolationist foreign policy position, which his administration translated into the systematic withdrawal of the United States from international treaties (the Paris climate agreement and the nuclear agreement with the Iran, among others) and international organizations (such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the World Health Organization (WHO)).

Trump also attacked the military alliance between European and North American governments (enshrined in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization,NATO) and hampered the functioning of the World Trade Organization (WTO), weakening the multilateral approach to international trade and launching his unilateral trade war against China.

A war whose side effects did not spare long-standing allies both in Europe and North America. In short, with Trump the United States someway paradoxically renounced its role as guarantor of a world order designed largely in its image after World War II. From America First to America Alone the step was short.

Made in all of America

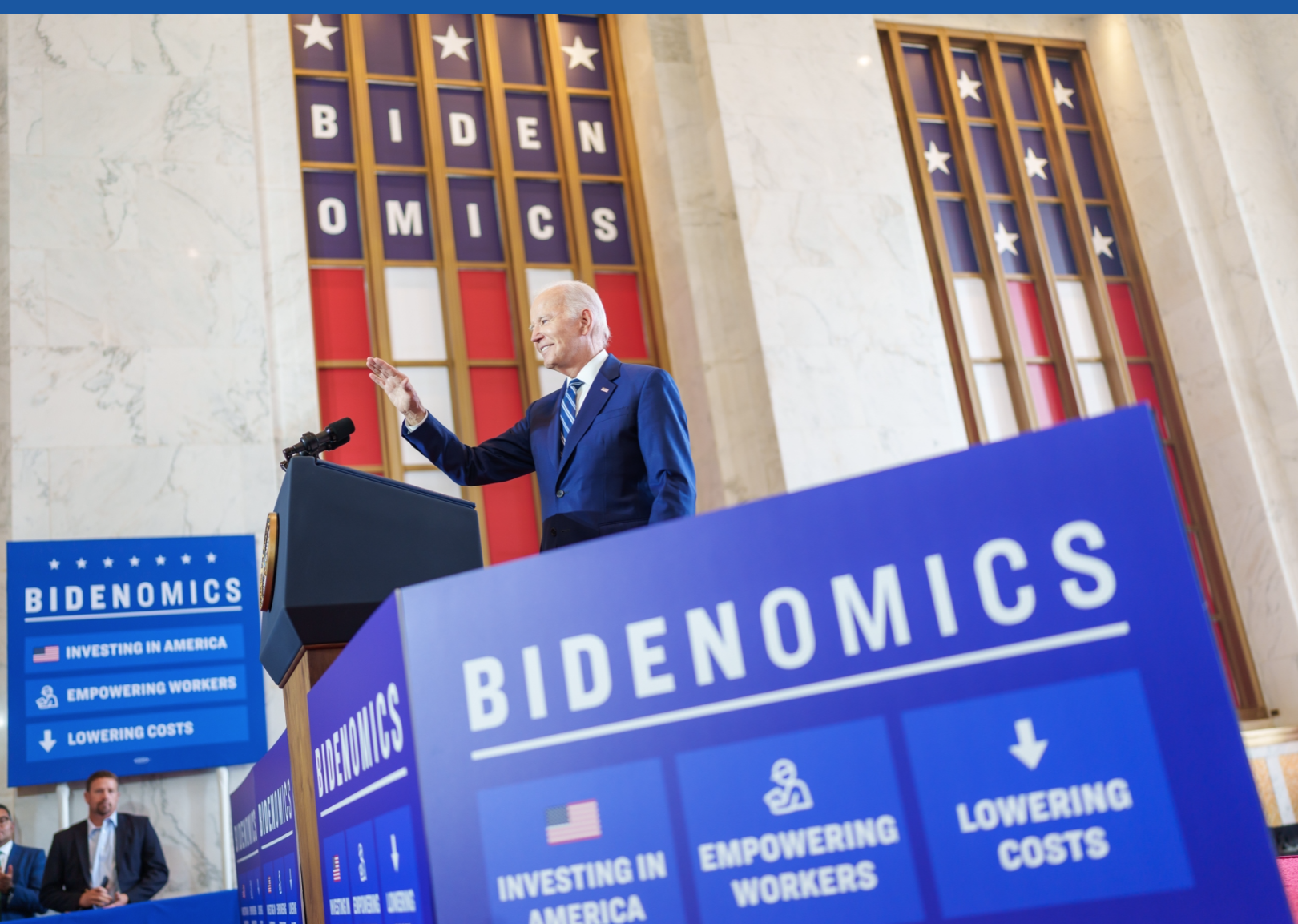

Since the election of Joe Biden as POTUS in 2020, there has been a return to more coherence and clearer foreign policy objectives, heralded by the U.S. rejoining of the Paris climate treaty and rubber stamped by the American support of Ukraine against Russian aggression.

Under Biden's leadership, the United States has successfully reaffirmed its pivotal position on the global stage, regrouping their allies around common objectives.

However, those who had expected a major discontinuity in terms of trade policy and international economic policy coordination were disappointed. Firstly, albeit with less polite tones and less articulate rhetoric than his predecessor Barack Obama’s, Trump essentially perpetuated the protectionist trajectory that was already pursued by his predecessor and reinforced in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

Secondly, Biden’s programmatic manifesto on economic policy, made public during his election campaign, spoke clearly. Right from the title: “The Biden Plan to ensure that the future is “Made in All of America” by all of America’s workers”. From Made in America to Made in All of America.

The message was strengthened by the opening of the document: “[Biden] does not buy for a second that the vitality of U.S. manufacturing is a thing of the past. U.S. industry was the Arsenal of Democracy in World War II and must be part of the Arsenal of American Prosperity today."

The Biden Plan unfolded along six lines of action emphatically called: “Buy American”, “Make it in America”, “Innovate in America”, “Invest in All of America”, “Stand Up for America” and “Supply America". The envisaged tools for action included massive industrial policy interventions to support American businesses and restrictions on international trade.

On March 11, 2021, Biden won his first major economic victory as POTUS when he signed the American Rescue Plan Act into law as part of his Build Back Better Plan, which also included the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan. Although neither of these passed Congress, some of their parts were assimilated into the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of August 2022.

On the industrial policy front, lines of action (many of which eventually made it into the IRA) included an ambitious public procurement program designed to benefit American companies, the project to eliminate from the American tax system the advantages that companies have in moving their production activities abroad, and the introduction of opposite incentives aimed at repatriating such assets, especially those deemed critical to national interests.

In terms of trade restrictions, the Biden administration posed a remarkable emphasis on ensuring that all traffic of a commercial nature between American ports takes place only on American ships built in America and with American crews.

In terms of national security, the Biden Plan is unequivocal: America no longer wants to depend on foreign suppliers for anything that could prove to be of strategic importance in a crisis situation.

A pretext to discriminate

An additional remarkable aspect was the unveiling of a strategy to decouple American supply chains from the Chinese (but not only Chinese) ones, at a time when the Covid-19 pandemic was not yet on the radar. The administration also expressed its willingness to include defensive social clauses in international trade agreements to fend off imports from countries with less stringent labor protection standards than those upheld by the United States.

All of this has been pursued by the United States in the name of “national security”, interpreted as the freedom to pursue the national interest without external interference or impositions.

From this perspective, a country’s s ability to maintain and develop its national economy is considered essential: the US believes that, without economic security, national security is compromised, as economic independence largely determines the autonomy of the nation.

In terms of national security, the Biden Plan is unequivocal: America no longer wants to depend on foreign suppliers for anything that could prove to be of strategic importance in a crisis situation.

However, the risk is that “national security” could become a pretext to be used when needed to discriminate against foreign companies as it is an exception that countries can invoke to legally derogate from the multilateral agreements sanctioned by the WTO. For example, Moscow invoked national security to impair Kiev’s foreign trade even before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The problem is that “national security” is an elusive and potentially dangerous concept. On the one hand, the notion that “national security” is underprovided without active state intervention implies that it must be associated with some positive “externality”.

An externality is an outcome of private actions that the private sector cannot evaluate correctly; also the public sector struggles to properly assess externalities, which makes it difficult to compare the costs and benefits of public policies for the taxpayers who are eventually handed the final bill.

On the other hand, the belief that a country can achieve its own “national security” abstracting from “international security” has repeatedly proved to be delusional in the course of history, and it is even more likely to be proved so today in an age of renewed global challenges.

Call it the “Maginot line mentality”. In the interwar period France wrongly believed to be safe behind its invulnerable protection system built at the border with Germany. Since then, the line has become a metaphor for lavish efforts offering a false sense of security.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.