Policy Brief n.8 - The Banking Union, Ten Years After

Even though European banks do have solid Basel ratios, their profitability is insufficient to make them attractive for investors. This suggests that – from the market’s perspective - the system may not be as sound and stable as regulators believe

-

FilePB08_Banking Union, Ten Years After.pdf (1.01 MB)

Ten years after the launch of the Banking Union, it’s time to assess what has been achieved. The project had two main objectives, i.e. to: 1) ensure the stability, safety, and soundness of the European banking system. 2) increase financial integration.

The second objective is the easier one to assess, as it has clearly been missed. As the SSM itself recognized:

“The situation did not change significantly… the banking sector is still, by and large, a collection of national banking sectors.”

It’s difficult to disagree with such a diagnosis. It may be a bit more difficult to agree on the responsibilities for such a failure. However, it cannot be denied that national regulators and supervisors have played a major role, by maintaining – and in certain instances even raising – the barriers for cross-border activity. The absence of a true European capital market also proved to be an important obstacle to achieving a more integrated banking system.

I will not elaborate further on this issue. I will rather turn to the other objective of the Banking union, which is the stability, safety, and soundness of the European banking system.

There are (at least) two ways to assess whether and to what extent this objective has been achieved. The first is to use the criteria used by regulators and supervisors. The second is to follow a broader, more holistic approach.

The first view can be easily gathered from recent SSM reports. The European banking system is generally considered to have become more resilient, especially considering the challenges that have emerged because of the sharp rise in interest rates worldwide. However, as expected from any supervisor, such an assessment is accompanied by the (usual) recommendation that there should be no grounds for complacency.

The supervisor’s assessment of the soundness and stability of the European banking sector is based is a series of solvency and liquidity parameters, such as:

-

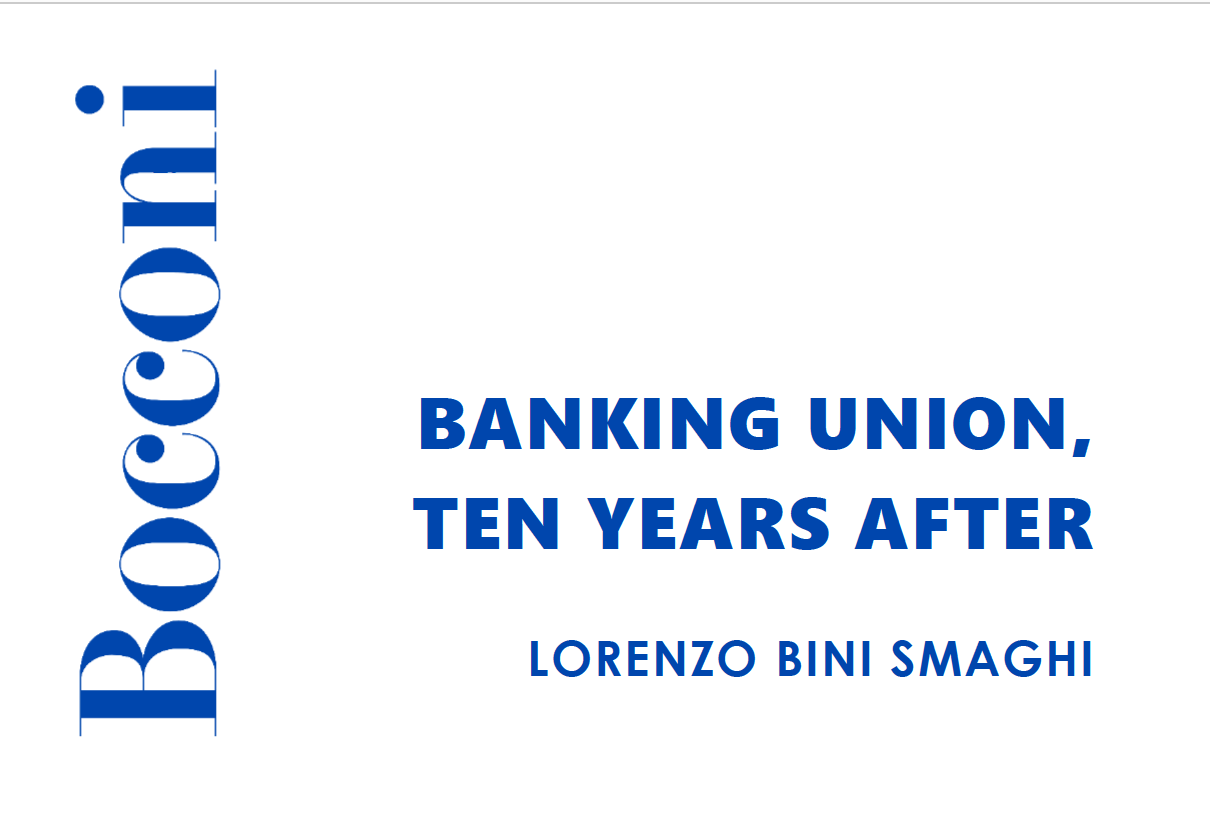

the Cet1 ratio and the leverage ratio (Chart 1), which increased in recent years;

-

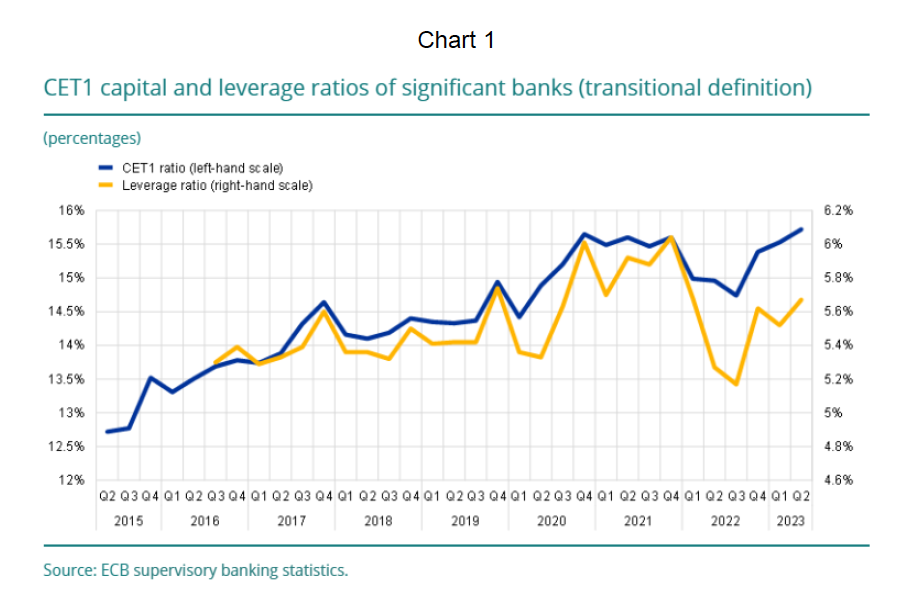

the share of non-performing loans (Chart 2), which declined sharply;

-

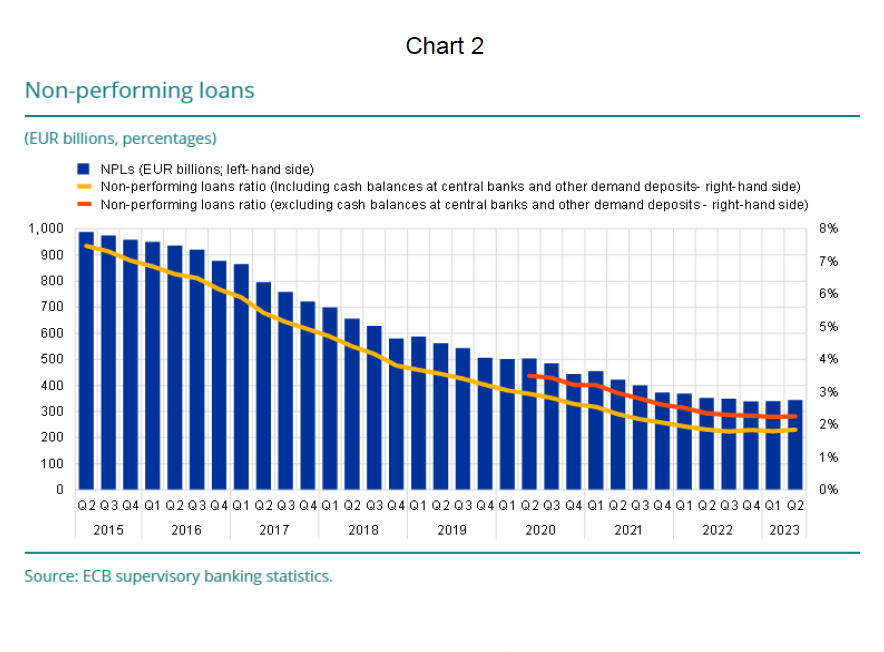

the funding ratio (Chart 3), which also improved;

-

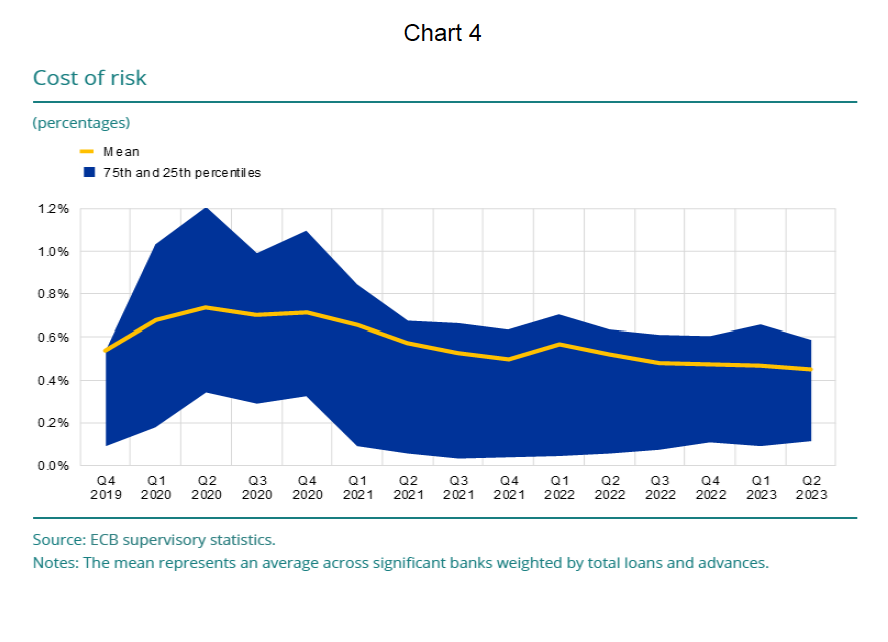

the cost of risk (Chart 4), which has remained low, despite the Covid and energy crises (and the warnings by the SSM), etc.,

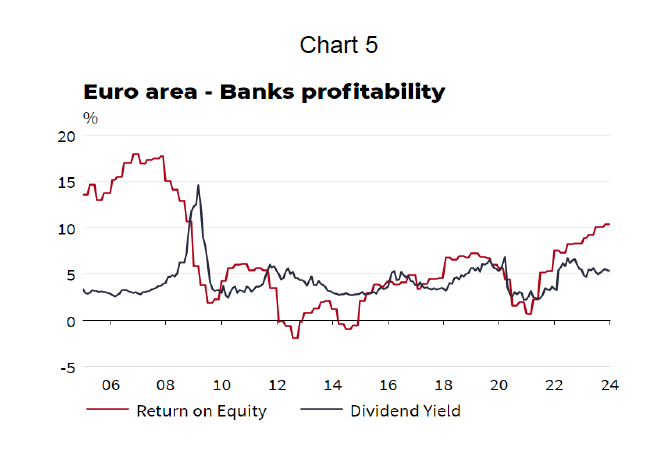

Furthermore, European banks navigated last year’s turmoil in a better situation than others. Even banks’ profitability has risen recently (Chart 5).

On this basis, there are no doubts that the European banking system is more stable, sounder, and safer than ten years ago. There are also no doubts that this result has been achieved thanks to the work that has been done over the last decade by the SSM.

This is one way of looking at things. But it’s not the only one. While the above-mentioned parameters are certainly correct, they do not provide a complete picture of the situation. Examining the issue from a financial market perspective, the assessment seems to be quite different, both in absolute terms and compared with other banking systems, particularly the US. Even though European banks do have solid Basel ratios, their profitability is insufficient to make them attractive for investors. This suggests that – from the market’s perspective - the system may not be as sound and stable as regulators believe.

I will try to explain why this is the case and what are the consequences for the European economy. To be clear, markets are not always right. But it would be a mistake for the policy authorities to ignore the markets’ views and warnings.

Let’s start by examining the markets’ assessment. A key indicator of the market valuation is the banks’ price-to-book ratio (Chart 6). It is used to compare the current market price of a company's stock to its book value. In the euro area, the average price-to-book ratio of banks currently stands at around 0.7, substantially lower than in the US (1.2). The price-to-book of European banks has been consistently below 1 since the Global Financial Crisis, while it returned above 1 in the US around 2014 and broadly stayed there since then. This is a signal that investors are not interested in buying European bank stocks, despite the large price discount.

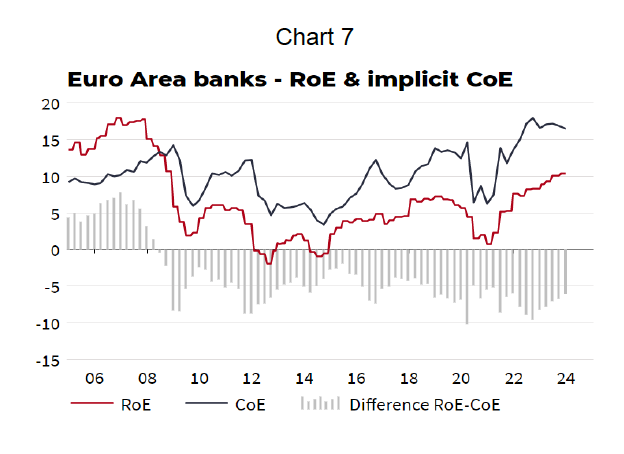

What is the reason for that? European banks’ earnings remain substantially below the compensation expected by investors for holding bank equity, i.e. the cost of equity (CoE). The average European banks’ Return on Equity (RoE) is currently around 10% whereas the estimated CoE stands at around 17% (Chart 7).

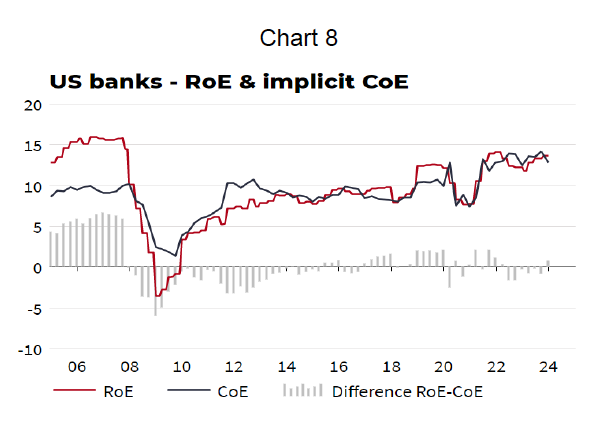

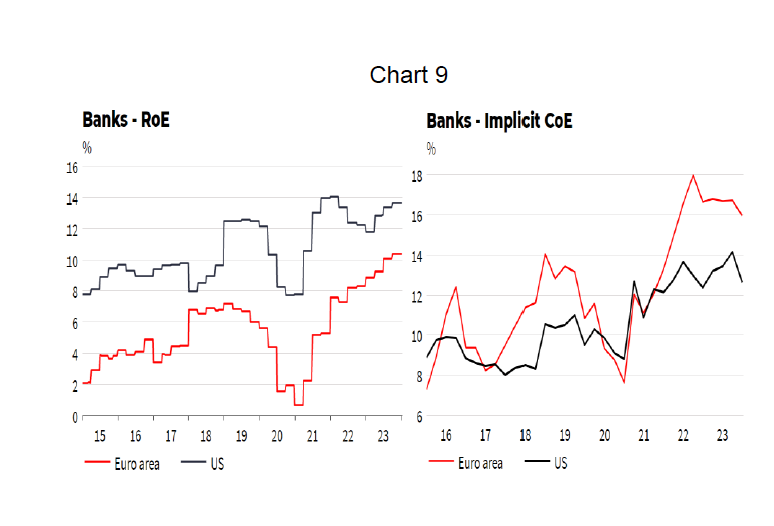

This is not the case in the US, where ROE is in fact slightly above COE (chart 8). In comparison with US banks, European banks have not only a lower RoE but also a higher CoE (Chart 9).

Furthermore, European banks’ RoE and CoE compare negatively with those of other European companies, in sectors like Energy, Tech or Pharma (Chart 10). It is sometimes forgotten, especially by academics and supervisors, that investors are not obliged to hold bank shares. They can sell them if they are not happy with the risk-return profile and buy shares in other more attractive sectors, which is what they have been doing. This explains the weaker performance of EU banks not only compared to the US but also to other European sectors.

Let’s briefly examine the main reasons behind the lower RoE and the higher CoE of European banks, compared to the US.

Starting with the lower profitability of the European banking system, some factors are idiosyncratic, dependent on the specific features of individual banks, while others are of a structural nature. Focusing on the structural factors, at least five can be identified.

The first, and most important one, is the absence of a European capital market, which would enable banks to roll over more efficiently their balance sheets. The difficulty to securitize loans and distribute them to market participants through liquid instruments forces European banks to hold to maturity a larger proportion of the assets that they originate, which is highly inefficient. As a result, European banks’ balance sheets are larger and less remunerative than those of their US counterparts.

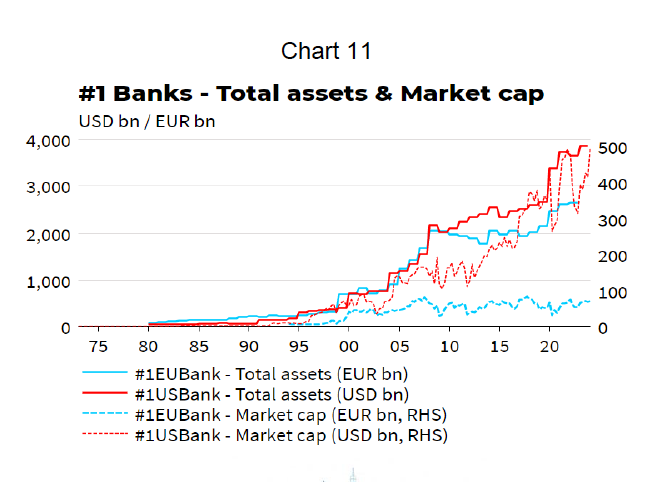

This is shown by comparing the largest bank in the Euro area and in the US, in terms of balance sheet and market valuation (Chart 11).

The size of the two largest banks across the Atlantic was broadly similar until the Great Financial Crisis, but the #1US bank was valued at about twice the #1Euro bank. After the GFC the #1US bank’s balance sheet nearly doubled in ten years, especially after the Covid and the March 2023 regional banking crisis, while the size of the #1Euro area bank remained relatively stable and increased slightly only in the last few years. The valuation of the largest US bank rose to eight times that of the Euro area bank, which remained broadly stable.

The second factor is the relatively higher fragmentation of the European banking sector, which compresses margins and reduces the ability to set prices. This applies to all sectors, including retail, corporate and investment banking activity.

The third factor is the relative rigidity of the European labor markets, which makes it much more difficult for banks to adjust costs to revenues, which largely depend on the macroeconomic conditions.

The fourth factor relates to the different policies implemented on both sides of the Atlantic. The negative interest rate policy adopted by the ECB from 2014 to 2022, which was never followed by the Federal Reserve, de facto implied a taxation on European banks, which could not pass the lower rate on to their customers. Direct bank taxes have also been raised in several countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Sweden, Lithuania, and Spain) on the presumption that banks were unduly benefitting from higher rates, while profit margins have in fact been lower than other sectors, have further penalized, and discouraged, bank shareholders.

Finally, the more restrictive way in which the Basel regulatory changes have been implemented in Europe may have negatively affected profitability, compared to the US.4 This is a controversial issue, where banks and regulators tend to disagree.

As mentioned previously, while profitability improved recently, especially since interest rates increased, bank valuations have continued to disappoint. The main reason is the cost of bank equity, which has remained elevated in Europe and even increased recently. This is a key issue that regulators tend to ignore. In theory, regulation and supervision should reduce the cost of equity over time, by making the system more stable and sounder. In practice, the opposite seems to have occurred.

Understanding the cost of equity is not easy. Research conducted by central banks tends to focus on bank-specific factors, such as the level of capital, the NPL ratio or the Cost-to-income ratio.5 Other factors, that affect the broader uncertainty surrounding the long-term profitability of the banking sector have instead been ignored.

In fact, the uncertainty about the European regulatory and monetary framework has played a major role in raising banks’ cost of equity. Let’s consider a few of these factors.

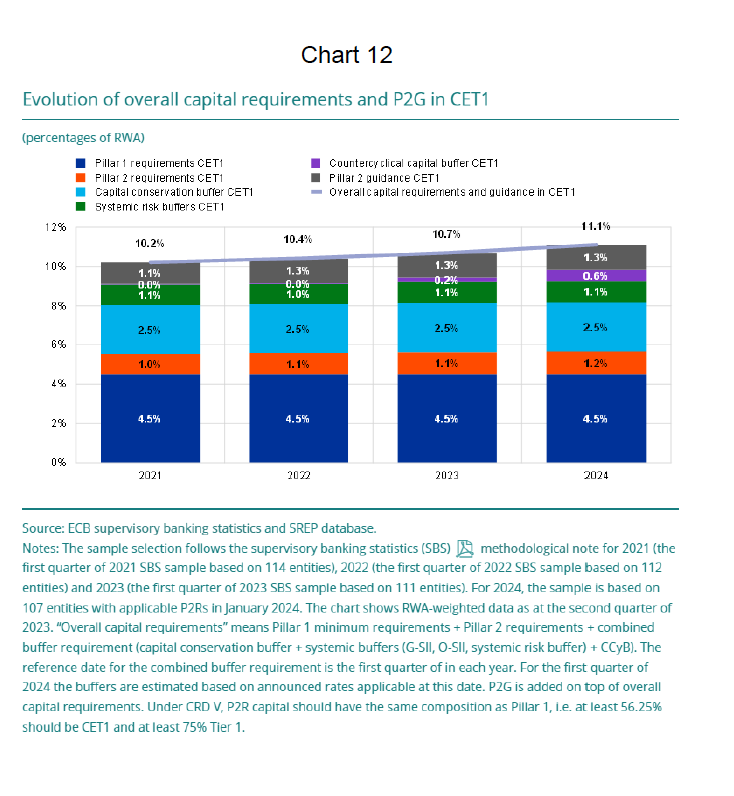

First, the regulatory cycle that followed the financial crisis – with the Basel reforms – was supposed to be completed and implemented by the middle of this decade. This is not the case. The implementation is leading to a continuous upward revision of capital requirements, without any prospect for stabilization. This is openly recognized by the ECB, which confirms in its publications the expectation of an open-ended process (Chart 12). Between 2021 and 2024 the average capital requirement has increased by 90 basis points. There are no indications that this trend will end.

Second, the review of the supervisory process (SREP) has created the expectation that the authorities will increase the resort to sanctions and penalties, in the pursuit of new supervisory priorities such as climate or cyber security.

Third, national authorities have continued to maintain obstacles to the cross-country mobility of liquidity and capital, and in some cases have even added new obstacles, like the (temporary) prohibition of transferring dividends within groups. There is also huge uncertainty about the treatment of cross-border mergers and acquisitions, as experience suggests that capital requirements may be unexpectedly tightened just before the finalization of the approval process, thus increasing the overall cost of the operation.

Fourth, the contracyclical capital buffers, which are decided largely at the national level as part of the macroprudential toolkit, have been used recently in a pro-cyclical fashion, contrarily to their original purpose, partly to offset the excessively expansionary monetary policy. The buffers have become permanent and may even rise further in the future, creating additional uncertainty.

Fifth, the dividend ban decided in 2020 and removed later than other central banks and the cumbersome authorization process for conducting share buybacks have created the impression that the ECB aims at exercising a tight oversight role, or even a moral suasion, over banks’ dividend policy. The public communication by the SSM has not dispelled these concerns.

Sixth, the contributions to the Single Resolution Fund have been very costly for bank shareholders over the last decade. They are expected to end in 2024 but unnecessary uncertainty has been created on whether the Fund is sufficiently large to address a crisis and whether further contributions could be required in the future. The non-ratification of the ESM as a fiscal backstop creates additional uncertainty. Concerns have been raised, after the Credit Suisse crisis, about Europe’s ability to address similar cases. The widespread response of several academics and policy makers is that capital ratios might need to be raised further.

Seventh, several ECB decisions created new uncertainty about the liquidity framework available to European banks. In particular, the decision to retroactively change the remuneration of the TLTRO, pushing banks to reimburse central bank liquidity in advance, affected banks’ ability to manage assets and liability maturity mismatches. The decision undermined the credibility of such an instrument and created additional risks for liquidity provision.

Eight, the ECB has openly discussed the possibility of further raising the zero-remunerated reserve requirements for banks – above the 1% decided last year, which would represent a further tax on banks. The implicit intention is to restore the profitability of national central banks, following their decision not to share the risks and returns of the asset purchase program and the insufficient provisions taken in the past.

Nine, the ECB launched a strategic review of its operational framework, with the stated intention to incentivize a return to the pre-2007 situation, in which the central bank would leave to the money market the determination of short-term rates. There is a serious risk of underestimating the complexity of restarting an interbank money market and the impact of discontinuing fixed-rate-full-allotment liquidity tenders, which could lead to higher costs of liquidity provision for European banks.

Finally, the ECB is actively pursuing the objective of introducing a Central Bank Digital Currency, that would compete with banks’ private means of payment. This could potentially reduce the size of banks’ private deposits and add instability to banks Assets-and-Liability management. Other central banks like the Fed have been much more cautious in avoiding entering private sector business.

It is not easy to measure the impact of all of the above policy decisions or intentions on banks’ CoE. To be sure, they fuel uncertainty about the prospects for European banks’ profitability over time and the viability of their business model. This explains why valuations of bank shares have been disappointing, with respect to other sectors and other countries, particularly the US.

Does it really matter if the banking system is undervalued? For many policymakers, the answer is negative. Let me explain why they are wrong, for at least four reasons.

First, an undervalued banking system, which is not attractive to investors, has greater difficulties in recapitalizing in case of losses. This makes the system more fragile, especially in case of crises.

Second, if capital is not remunerated in line with cost, managers and boards are under pressure to return part of the capital to shareholders, through share buybacks. This pushes banks to shrink their balance sheet and to refocus their business, largely towards the domestic sector that they know better and in which they have greater market share. This produces several effects. The first is to further increase fragmentation in the European banking markets, thus generating a vicious circle if all banks move in the same direction. The second effect is that European banks tend to abandon subscale businesses to larger US banks that can better exploit economies of scale, in particular concerning trading activities, investment banking, treasury, and depository services, etc. These are essential services for the development of a European capital market.

Considering for instance the two major market activities, Fixed income and equity, between 2009 and 2022 the share of the first 4 banks in the global market has moved from around 40 to 60%, with no major European bank left in this group. European players have become sub-scale, and several have abandoned the market, especially in the equity sector (chart 13).

It is an illusion to think that a European capital market can be developed without the contribution of European players, such as investment banks, market makers, asset managers, and analysts. As European actors reduce the presence in these sectors, the likelihood of developing an integrated capital market in Europe vanishes.

Third, to generate excess capital to return to shareholders, banks tend to reduce lending to the real economy. The overall flow of credit has decreased as a percentage of GDP since the great financial crisis. This obviously hampers economic growth. It is also a major impediment to achieving the huge financing requirements for the energy transition and the digital transformation over the coming years.

The above suggests that an undervalued banking system can generate less credit and provide fewer services to European companies and households, thereby hampering Europe’s competitiveness and growth potential. The expectation, or hope, that the reduction in banks’ flow of credit can be compensated by an increase in the shadow non-regulated channel may not be fulfilled and does not meet the same stability requirements. A healthy European economy can only be based on a healthy European financial system. European policy makers have a hard time understanding this equation. This is the key difference with the US.

To sum up, the European financial system may a short sight look sound and stable but is much more fragile. More importantly, and possibly more difficult to admit, such a fragility is produced by specific policy actions. The experience of the past decade suggests that the European Financial regulation and supervision suffers from what economists call a fallacy of composition. Each single measure may make sense by itself but the sum of all the measures leads to a suboptimal and unstable result.

Ten years later, the time may have come for rethinking the European regulatory and prudential framework. Such a rethinking should start from admitting that the objectives of the Banking Union have not been fully achieved and that the system is not as strong as expected. The responsibility largely lies in the way in which the framework has been implemented and in the uncertainties it generates. The ultimate cost of failure will be paid not only by the financial sector but by the whole European economy.

Revised version of “The Future of Financial Regulation and Supervision in Europe” 12th Conference on the Future of the Financial Sector, Frankfurt, 19 January 2024.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.