The Problem with the Dublin Regulation

Without a serious change in the regulations, or a substantial investment in the bureaucratic capacity and the infrastructure for migrants, Dublin is bound to be more real on paper than in practice and many ports of entry are likely to remain in a constant state of emergency.

Just before the Christmas break European Parliament and Council reached an agreement they hail as “historic”, which is supposed to replace the current Dublin regulations on the handling of migration and asylum applications to the EU.

The details of this agreement have not been published yet. This note only provides some background information on the gulf between legal theory and reality for the core element of the current system, i.e. the Dublin regulation.

The core of the 1990 Dublin regulation, which is in its third “restyling” in its current form with Regulation No. 604/2013, can be summarized in one key principle: migrants wishing to apply for asylum in the EU must do so in the first country to which they arrive in the EU.

This means that the Member States along the borders of the EU – especially the southern ones – have come under great stress in the past few years, being the first port of entry for many migrants following the Mediterranean routes.

According to the standard Dublin procedure, a migrant rescued in the Mediterranean and taken to the nearest, say, Italian port should be identified by Italian authorities, present her asylum application to Italian courts, wait for the court’s decision (which in many cases can take years) in Italy, and only if the asylum is granted can she lawfully move and live anywhere in the Schengen area.

Should this migrant instead be able to reach another EU country without a visa, e.g. Germany, and present her asylum application there, then under the Dublin regulation German authorities can ask to transfer the migrant to Italy, where her asylum application should be evaluated.

This is how things should work on paper. The reality is quite different.

First of all, several non-border states receive more demands for asylum than those on the border. Second, the distribution of asylum seekers across Member States does not follow the rule book.

Does Dublin leave all asylum pressure on border states?

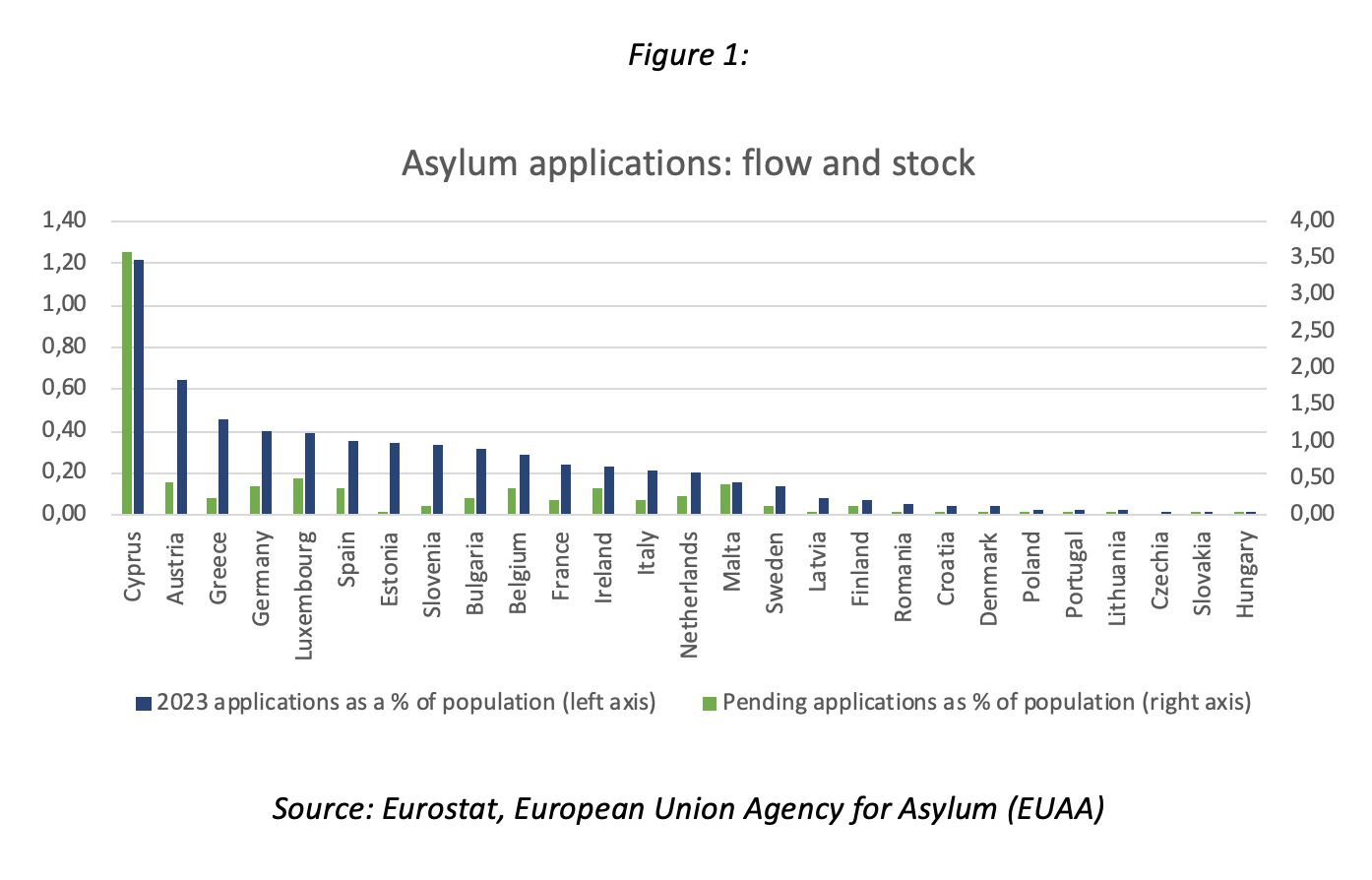

Figure 1 shows the stock of pending asylum applications in percentage terms of the population at the end of September 2023 and the arrivals in 2023 (at annual rate, i.e. based on data up to September 2023, assuming Q4 is the average of the previous three quarters).

For most countries, the flow of new arrivals is much higher than the stock. This means that arrivals have clearly increased, putting pressure on the system of processing asylum demands in many countries.

Another clear message is that border states are not the most concerned by this surge.

Italy, one of the main ports of entry from the Mediterranean, is not even in the top 10 countries in terms of applications per capita. And a landlocked country such as Austria has seen one of the highest application rates per capita.

Can non-border states send asylum seekers back?

As already described, according to the Dublin regulation, in principle the non-border countries could ask to transfer migrants to the port-of-entry country, to present their application there. And they do. The problem is that simply put, the port-of-entry country can just ignore the request or refuse the transfer. This is often the case.

Figure 2 shows, for the case of Italy, a comparison between the transfer requests made by other Member countries and the actual transfers that have taken place. Only around 11% of Dublin transfer requests are executed. Since 2013 Italy received 310.000 of so-called Dublin requests for transfer, of which only 35 thousand were executed.

Need for real change

Pending requests in Italy have grown by 50% from January to September 2023. Its asylum system is running past capacity and room for accepting transfers is very scarce. Without a serious change in the regulations, or a substantial investment in the bureaucratic capacity and the infrastructure for migrants, Dublin is bound to be more real on paper than in practice and many ports of entry are likely to remain in a constant state of emergency.

This is detrimental for the dignity and safety of migrants, for the correct functioning of legal protocols and for the attitudes of the local populations towards migration – and towards Europe.

Whether the newly proposed regulations can make an effective enough change remains to be determined, but the current situation results in a rather high requirement for what it will take to be deemed as “historic”.

New Pact on Migration and Asylum, Historical Agreement or Broken Deal? Read Angelo Martelli's commentary

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.