The Quiet after the Storm: Why We Should Worry about the Banking Sector

The global financial system is at a crossroads of two related processes: post-crisis reform—the so-called Basel III—that is missing its final stage, and the new political course in the United States, where the incoming administration has declared war on all pre-existing rules.

When is the right moment to deal with (or worry about) banks? If we look at Google Trends, we see that in recent years, only on three occasions have banking issues disturbed people’s sleep: 2008 (the great financial crisis), 2020 (the pandemic), and 2023 (the crisis of regional American banks). In all three cases, the concern lasted briefly: a month or two at most.

But to be truly aware and effective, policymakers and depositors should harbor doubts especially when there appear to be no clouds on the horizon. That is the most fruitful and least costly time to understand and, if necessary, act.

This could be one of those moments. The two years since the last crisis of U.S. regional banks are coming to a close. A crisis that, without warning, shook the American financial system and part of the global system. What happened, and why? Which lessons are still relevant today?

To answer these questions, we must pay attention to three things: how that crisis began, how it was resolved, and what consequences it had—or did not have—elsewhere in the world. Some answers can be found in a report published a few months ago by CEPR, the economic research institute based in Paris, written by the author together with a group of European and American expert.

Analysis of a Sudden Crisis

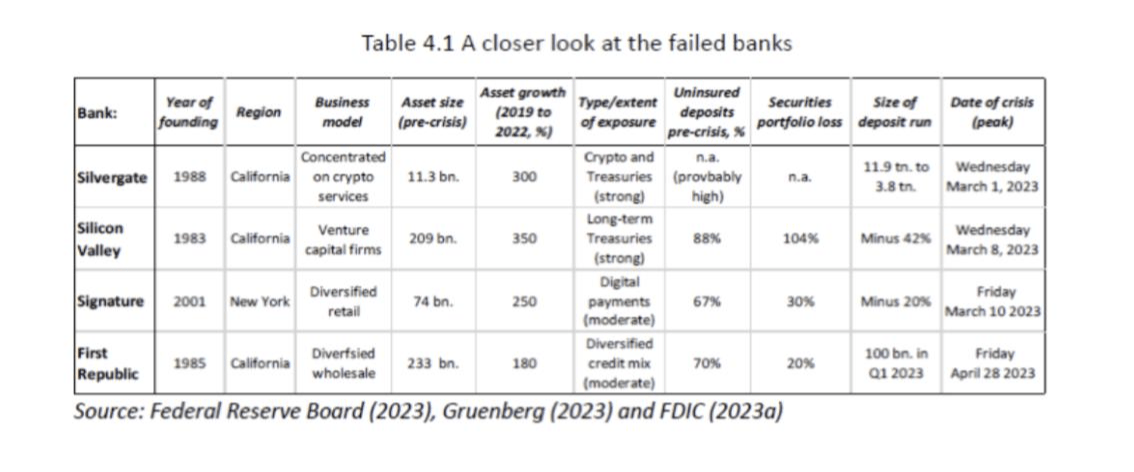

The banks that collapsed in March 2023 had little in common: not their geographic location (Silicon Valley Bank was based in California, Signature in New York), nor their business model (First Republic had diversified lending, while Silicon Valley was focused on the innovative venture capital sector, and Signature operated in cryptocurrencies), nor an excessive propensity for risk-taking.

The common feature, which could have raised alarm, was the fact that all had grown disproportionately in a short time due to a massive influx of deposits from large investors, which, due to their size, exceeded the deposit insurance coverage limits.

This highly unstable liquidity was “parked” at the central bank, making it entirely safe, and invested in long-term government securities or government-backed securities. While these were considered safe, they were actually exposed to the risk of rising interest rates, which materialized violently and unexpectedly from 2022 with the onset of inflationary pressures.

The depositors’ flight—predictable at that point but surprising in its scale and speed—jeopardized the banks’ securities portfolios, which had been devalued due to rising rates. It mattered little that the banks had preemptively classified the securities as held to maturity (HTM) rather than available for sale (AFS). This classification exempted them from reporting the losses on their balance sheets, but depositors calculated their market value (mark-to-market), concluded that at those values, the banks were technically bankrupt, and “fled”—primarily towards larger, more solid banks.

Here are two key lessons to keep in mind: in the era of online banking, deposits move more quickly than before, especially when concentrated in a few hands. And the fact that banks are exempt from reporting certain losses on their balance sheets does not reassure depositors.

The focus of banks and regulators must shift, in part, from balance sheet data to market prices (mark-to-market losses) and to the portion of funding not covered by deposit insurance. The higher these two parameters, the greater the bank’s risk.

Caught off guard, U.S. authorities reacted by the book: supporting the troubled banks as long as possible while seeking sufficiently strong buyers.

Deposit insurance was expanded, and the central bank refinanced the system. Success was almost immediate; deposit outflows ceased, and the banks—or parts of them—were closed or acquired by other banks. The rapid stabilization was largely due to two factors: a highly experienced resolution authority, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)—whose chairman, incidentally, was recently dismissed by US President Donald Trump without a word of thanks—and the fact that it had effective tools at its disposal.

Three in particular: a solid deposit insurance fund with unlimited access to Treasury funds, which could later be recovered from banks; the authority to take control of failing banks and directly manage the crisis (the so-called receivership); and, in extreme cases, the power to change the rules by extending deposit coverage (systemic exception).

From this, another lesson emerges: when a crisis begins and deposits flee, the stabilizing action of the authorities must be immediate and overwhelming—greater than the minimum necessary.

A priori, it is never possible to know exactly where that minimum lies, and a posteriori, it is always unclear whether the actions taken were truly necessary to achieve the goal. The authorities will always be accused of "bailing out the bankers"—such accusations are part of the job of those who oversee financial stability.

What matters is that, at the crucial moment, fleeing depositors are convinced that the authority has the means and the determination to carry out an overwhelming action.

Meanwhile, in Europe

Reflecting on that experience through the lens of our own context, it is concerning that the analogous European authority, the Single Resolution Mechanism based in Brussels, does not have any of the three elements mentioned above.

It cannot rely on unlimited deposit insurance coverage, nor on the limited support of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM, the so-called "bailout fund"), as Italy has currently decided not to approve its reform; it cannot take direct control of a failing bank, but must always rely on national institutions, thus depriving the intervention of the necessary speed and decisiveness; finally, it cannot, as the FDIC did, change the rules to temporarily grant banks protection to overcome the critical phase.

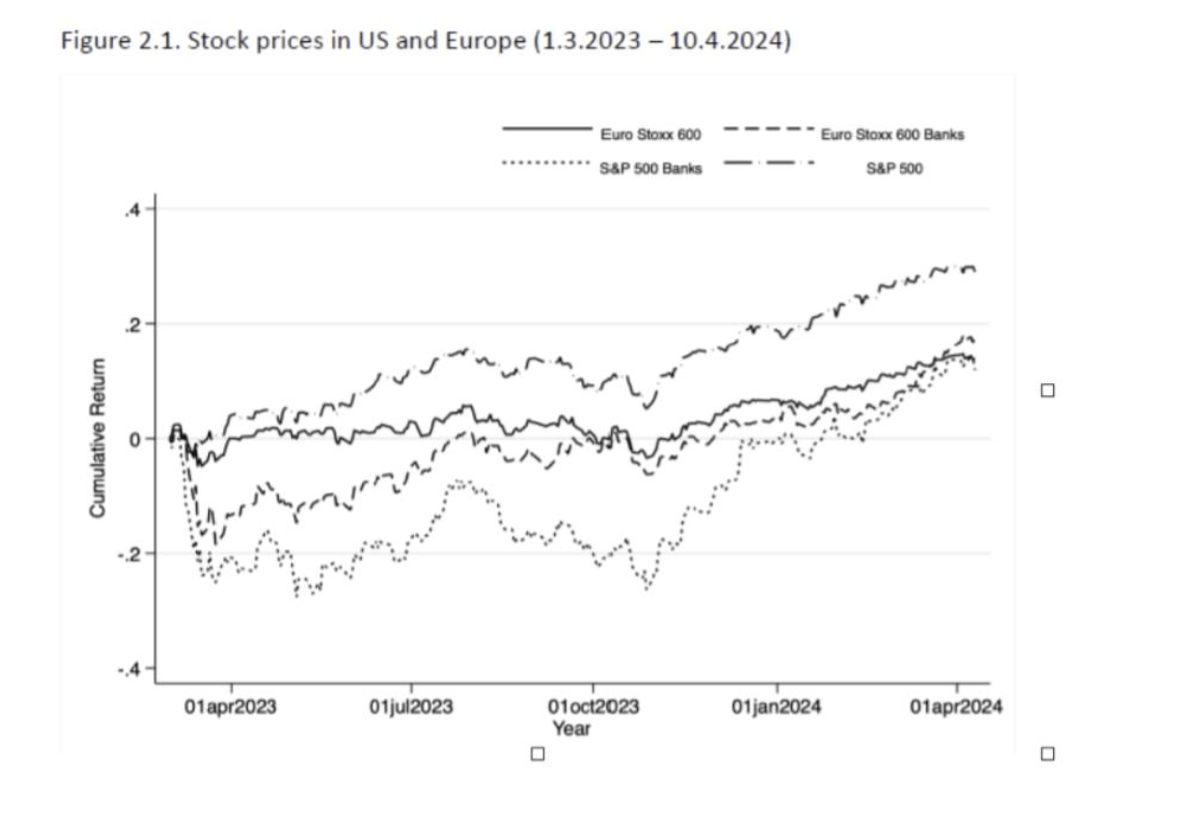

To see the third series of evidence and the lessons to be drawn, let’s shift across the Atlantic. The contagion from the American crisis was selective, not widespread.

Banks in the euro area were affected only briefly and to a limited extent; no bank failed, there were no public interventions, and the sector’s capitalization quickly recovered after a short-lived dip.

In contrast, in Switzerland, Credit Suisse, the country’s second-largest bank, collapsed after being in crisis for some time due to repeated losses and mismanagement. The deficiencies in Swiss oversight and the contrast with the excellent experience elsewhere in Europe illustrate the third lesson: the importance of preventive prudential oversight.

As an expert on these matters, Stephen Cecchetti, has written: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” For our banks, the fortunate circumstance—if one can use that term during a crisis—is that this crisis occurred after the ECB had cleaned them up and strengthened them with substantial injections of capital and liquidity, and not before.

Had it happened in 2013, rather than in 2023, the effect of the U.S. crisis in the eurozone—particularly in Italy—would have been far more severe.

Trump vs. the New Rules

All of this is relevant today. The global financial system is at a crossroads of two related processes: post-crisis reform—the so-called Basel III—that is missing its final stage, and the new political course in the United States, where the incoming administration has declared war on all pre-existing rules.

The final phase of Basel III (endgame, in industry parlance) involves higher capital requirements for the largest banks, which would face more stringent requirements on market and operational risks and would be required to mark losses on securities to market value on their balance sheets.

These revisions, although they predate the 2023 crisis, respond to some weaknesses highlighted by it, and are being opposed by the Trump administration.

Europe, which has supported them so far, seeing their adoption as beneficial for all, now faces the “prisoner’s dilemma”: continuing to support them alone would be particularly disadvantageous. Especially while facing the challenge, raised by Mario Draghi in his recent report, of making its financial system more integrated and competitive.

The challenge primarily revolves around large banks, as global competition centers on them, and because the new cycle of deregulation under Donald Trump will specifically target them.

It is regrettable to acknowledge, but it is better to do so sooner rather than later: the “final phase” of Basel III no longer seems feasible.

The priority for continental Europe now is to open the capital markets to large banks, following the guidelines suggested by the CEPR report and Draghi’s own report, promoting their expansion across Europe and strengthening them through combinations of different areas: traditional intermediation, investment banking, asset management, insurance, payments, and more.

Larger intermediaries could have greater systemic relevance, making crisis management more complex. Reforming the European resolution authority along the lines indicated seems even more urgent in this scenario.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.