Saving and Investments Union: Another Slogan or Something More?

Europe’s financial integration will succeed only if banks are placed at its core. A commentary by Ignazio Angeloni, and Marco Pagano

The Saving and Investments Union (SIU) now being launched in Europe can succeed — unlike previous attempts at Capital Markets Union — only if it is firmly anchored in the banking system.

This requires enabling European banks to grow in scale, scope and geography, creating European and global champions rather than nationally sponsored institutions shaped by domestic politics. EU regulation must be adapted to facilitate this outcome.

On that basis, market-building components should be added that reinforce the role of banks. We propose two: new personal and pension savings vehicles designed to channel funds into equity capital, and a European market-making platform for credit securitisation.

1. Saving and Investments Union: ambition and ambiguity

The European Commission’s proposals on the Saving and Investments Union (SIU) — notably the Market Integration Package presented in December, alongside earlier targeted initiatives — fit within a decade-long debate on strengthening Europe’s financial architecture.

The underlying intuition is clear. The European Union generates abundant private savings but struggles to channel them into productive, high-risk, long-term investment.

Yet what does the SIU concretely entail? Is it a genuine shift in European financial policymaking, or merely a rhetorical reformulation of familiar objectives such as the Capital Markets Union or the completion of Banking Union?

Without conceptual clarity, the SIU risks becoming a politically appealing slogan devoid of transformative content.

The real issue is not the proclamation of new goals but the identification of realistic and politically feasible instruments capable of aligning Europe’s financial system with its needs for growth, technological transition and strategic autonomy — in an international environment made more competitive by deregulation under the Trump administration and potentially emulated elsewhere.

Reconciling three objectives — market development, global competitiveness of European banks and the preservation of prudential soundness — requires strategies that are more radical than those so far embedded in the SIU framework.

2. Europe as a bank-based system

A starting point is unavoidable: Europe is, and will remain for the foreseeable future, a bank-based financial system.

Banks dominate financial intermediation, particularly in financing small and medium-sized enterprises — the backbone of Europe’s productive fabric.

Replicating the American model is neither realistic nor desirable, given institutional, legal and cultural differences between Europe and the United States.

The SIU should instead be conceived as a project of functional integration between banks and capital markets.

European banks must be seen not as obstacles but as indispensable vehicles for market development. Capital markets will expand only if banks are incentivised and enabled to participate actively.

3. Regulatory constraints and the limits of Banking Union

Debate on completing Banking Union has traditionally focused on three issues: a European deposit insurance scheme, strengthening the Single Resolution Fund’s backstop, and the treatment of sovereign exposures in bank balance sheets.

These are relevant for financial stability but politically contentious. Divergent national interests, differing risk perceptions and resistance to loss-sharing have stalled progress.

Moreover, even if fully realised, these reforms would not in themselves ensure greater market-based financing for firms nor the effective channelling of European savings into a genuinely integrated capital market.

The debate must therefore be refocused. Rather than insisting on institutional reforms blocked for years, policymakers should identify a less politically divisive strategy capable of equipping major European banks with both the capacity and incentives to act as agents of capital-market integration.

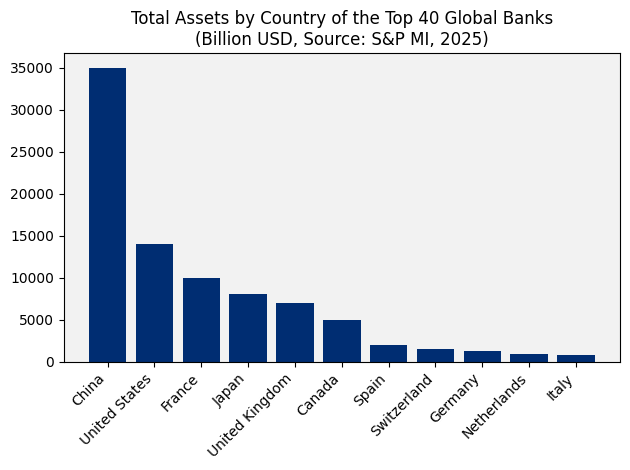

Capacity is lacking. According to rankings of the world’s 40 largest banks in 2025 by S&P Global Market Intelligence, European institutions fall well short of what the continent’s economic weight might imply.

Fragmentation along national lines weakens them further. Credit remains largely segmented by borders and is often provided by banks too small to compete effectively in investment banking and securities placement at a supranational level.

Beyond scale and international presence, European banks lack sufficient incentives to drive capital-market development. Household savings — which they largely collect — are predominantly held in simple bank deposits. Professional asset management remains underdeveloped, with partial exceptions such as France.

National governments and regulators often discourage cross-border expansion, seeking to retain savings domestically and facilitate the placement of public debt. European banking regulation itself has discouraged practices such as securitisation, despite their historical contribution to capital-market development elsewhere.

These structural constraints can be addressed within the SIU strategy through two complementary approaches: fostering the scale and international projection of banks to create a core group capable of competing globally; and stimulating private initiatives to build the missing “building blocks” of a mature financial structure.

4. Four lines of action

Banking Union, while effective in several respects, has not delivered an integrated banking system. Cross-border initiatives remain sporadic. Regulatory barriers — national and European — and political interference aimed at preserving domestic banking systems have limited consolidation.

The resulting equilibrium resembles a prisoner’s dilemma: efforts to protect national systems produce collective weakness.

First, euro-area banking activity should become fully equivalent to national activity. A proposal in the Draghi report suggests a “country-blind” supervisory and crisis-management regime for cross-border banks within Banking Union. Implementing this would require targeted regulatory adjustments to remove residual obstacles to cross-border operations.

Second, political convergence is indispensable. A coherent European regulatory framework cannot function if member states continue promoting nationally sponsored banking champions, as recent episodes in Germany and Italy have illustrated.

A shared commitment among major euro-area countries to support genuinely European cross-border banks is essential — particularly in light of geopolitical risks that demand greater strategic autonomy.

Third, savings policy must be reoriented. A recent report by the Institute for European Policymaking at Bocconi University proposes new individual and second- and third-pillar pension savings instruments, partially inspired by Sweden’s Investeringssparkonto (ISK).

These would incentivise investment in equity and pool savings at European level, accessible under equal conditions to private and public investors.

Fourth, credit securitisation should be rehabilitated. Stigmatised after the global financial crisis, securitisation — if properly regulated — can act as a catalyst for capital-market development.

A more favourable regulatory treatment combined with the creation of market makers to enhance liquidity of standardised securitised products could revive this market. While driven by private initiative, public support may be necessary in the initial phase.

The latter two initiatives combine market development with bank participation, reinforcing banks’ role in savings mobilisation and capital-market expansion.

5. Conclusion

For three decades Europe has sought to build an integrated banking union; for fifteen years it has pursued a Capital Markets Union. Progress has been significant but incomplete.

New global challenges and the quest for strategic autonomy require renewed effort on both fronts.

We propose four lines of action — two focused on banks and two on markets. They require limited but decisive political backing and depend largely on private initiative. They could be launched by coalitions of willing operators and countries, and need not be confined strictly within the EU’s formal borders.

The erosion of the so-called “old world order” may paradoxically facilitate such cooperation, drawing European countries — including the United Kingdom — closer together and highlighting shared interests that transcend formal institutional boundaries, alongside other middle powers.

A previous version of this article was publishedin the Italian monthly magazine ECO

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.