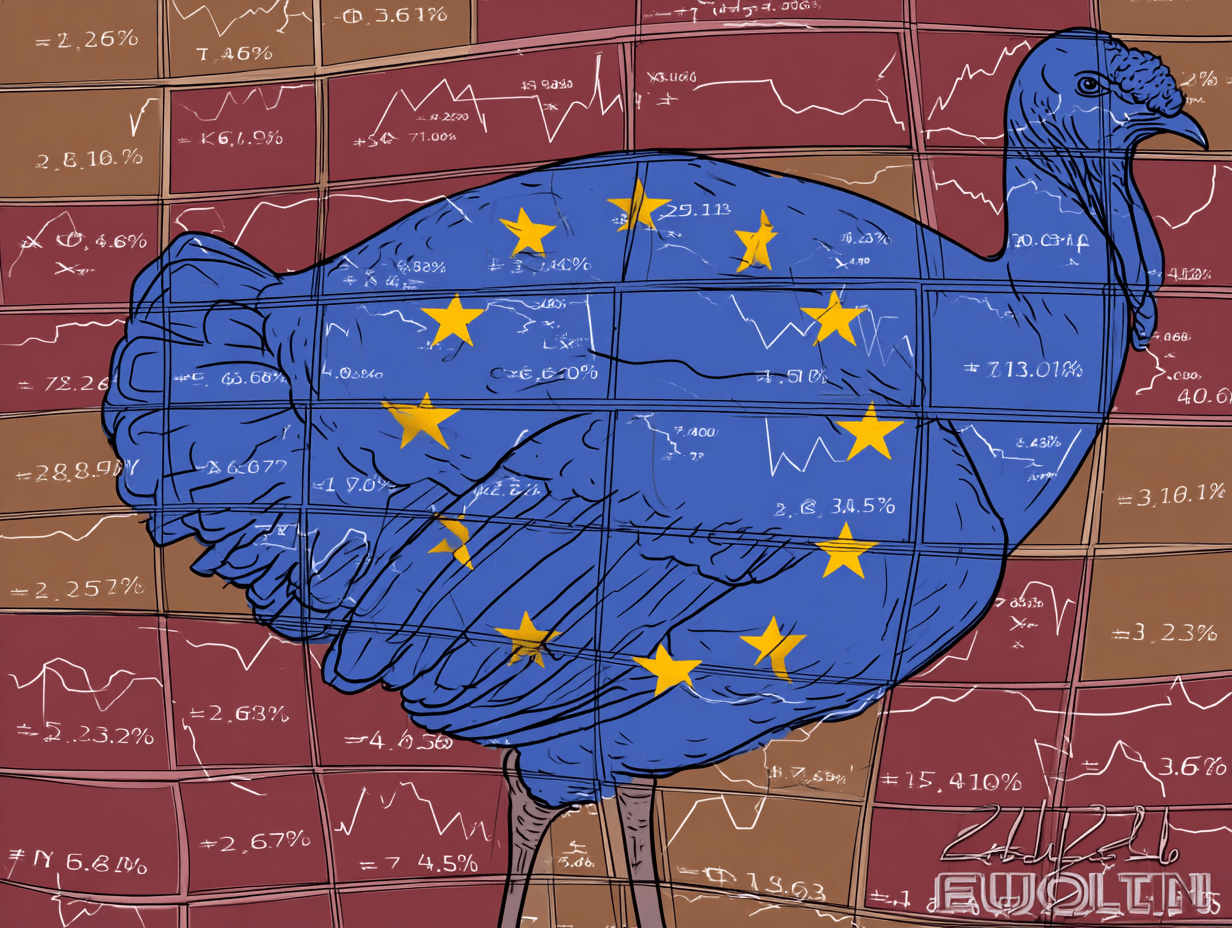

The Turkeys’ Survival Instinct Is Europe’s Undoing

Anyone who holds even a small amount of power clings to it and is unwilling to let go. This is why European countries are determined to keep their right of veto. A commentary by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi

The list of what Europe must do to confront its upcoming challenges is by now clear. The real question is how to break the deadlock—one that stems largely from member states’ unwillingness to relinquish their veto power and embrace joint decision-making.

An old English saying—“Turkeys don’t vote for Christmas”—aptly captures the problem. In other words: no one is willing to take decisions that might endanger their own survival. Even those with only minor power will hold on to it tightly, refusing to give it up. This is why European countries resist majority decision-making and cling to their veto rights.

This dynamic is at play at every level of decision-making, especially at the lower tiers of government officials and national regulators. The result is that even when the European Council—which groups the heads of government—reaches broad agreement, progress stalls as the discussion moves to the technical level, among ministers and civil servants. It is in these technical negotiations that the turkeys’ survival instinct is at its strongest.

The euro itself would never have been born had the decision been left to the central banks, who were well aware that a single currency would strip them of their remaining powers. It took the vision of bankers like Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa, who put the common good first, to convince political leaders that clinging to such power was an illusion, and that a single currency was in everyone’s interest.

The same holds for the decision in 2012 to unify banking supervision and regulation at the European level—a move fiercely resisted for years by national authorities, and only made possible by the 2011-12 crisis.

The problem recurs today over the objective of a fully integrated European financial market, governed by unified regulation and supervision. Achieving this is essential if Europe is to finance the massive investments needed in defence, the environment, digitalisation and artificial intelligence—investments that cannot be borne solely by public finances. There is, moreover, growing international interest in euro-denominated financial instruments as alternatives to the dollar.

The timing, therefore, is propitious.

The European Council has reiterated this goal on multiple occasions, spurred on by a succession of official reports and by calls—most recently from ECB President Christine Lagarde (“A Kantian shift for the Capital Market Union,” 17 November 2023)—for bold action. Yet progress remains painfully slow.

Once again, opposition comes primarily from national authorities. Their argument is that, unlike monetary union—which was established after the currency crises of the 1980s and 1990s—and banking union, which followed the great crisis of 2010-12, there is currently no capital markets crisis to force action.

In truth, the situation is far more serious. Europe’s national financial markets are gradually—and inexorably—disappearing, some faster than others. The evidence is in the declining number of transactions and the shrinking pool of listed companies. In a few years, only those with government ownership will remain.

A growing number of companies are migrating to the US market, attracted by its depth and liquidity, where they command higher valuations. The funds—often their main shareholders—actively encourage this migration.

Tax measures now being implemented by the US administration will deliver the final blow, providing further incentives for European firms to move their headquarters across the Atlantic.

Meanwhile, savings flows from European countries are increasingly being intermediated by largely unregulated, typically American, financial actors—whose political influence grows with every passing year.

In short, resistance to integration is leading to the desertification of what remains of European capital markets, for the benefit of Wall Street.

Contrary to popular belief, the obstacles are not the result of overregulation from Brussels bureaucracy, but rather from national bureaucracies and politics, intent on clinging to their last remnants of power and resisting the simplification and harmonisation needed for an efficient single market.

The responsibility for breaking the deadlock lies with the highest representatives of national governments—those to whom national bureaucracies ultimately answer.

A first version of this article was published in the Italian daily Il Foglio

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.