What Is Happening to the Euro Exchange Rate

By most fundamentals, the single currency should be weakening, yet it keeps rising against the dollar and other major currencies. It may have to do with the ECB’s monetary stance. A commentary by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi

Explaining the recent appreciation of the euro against other major currencies is not straightforward.

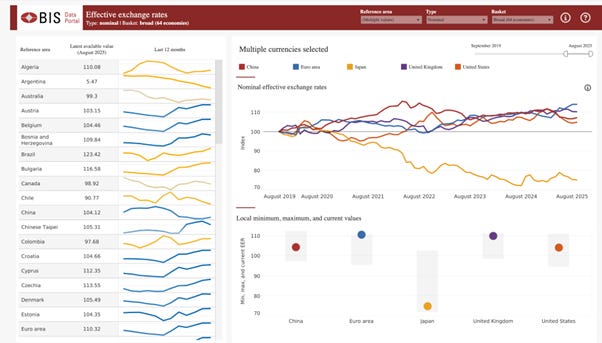

Since March, the euro has risen 15 per cent against the dollar, 13 per cent against the yen, and 5 per cent against sterling. In effective terms — that is, relative to the average of other major currencies — the euro has reached its highest level in 25 years.

Exchange rates, being the relative price between currencies, are influenced by several factors such as: trade balances, capital flows driven by interest rate differentials, and relative economic growth.

Yet none of these factors seems to justify the euro’s recent appreciation, especially against the dollar.

On trade balances, the restrictive measures adopted by the US administration should, if anything, narrow America’s deficit and Europe’s surplus, reducing upward pressure on the euro.

From a growth perspective, the latest data show greater resilience in the US economy, which is expected to expand more strongly than Europe’s in the coming years. Investment in high-tech sectors and fiscal stimulus continue to support activity across the Atlantic. Wall Street’s performance, buoyed by capital inflows from around the world, confirms this trend.

In Europe, by contrast, growth remains uneven: robust in Spain and parts of northern Europe, but weak in Italy and France, and even negative in Germany. Such divergence hardly supports a stronger euro.

Monetary policy differences should also, in theory, point in the opposite direction. Short-term interest rates have been cut more rapidly in Europe, now around 2 per cent, compared with 4 per cent in the United States.

The Federal Reserve still considers its monetary stance as restrictive, while the European Central Bank believes it has already exited the restrictive phase. Something, clearly, does not add up in the conventional exchange-rate narrative.

Part of the problem may lie in how monetary conditions are assessed in the two economies.

If one looks only at short-term rates, US policy appears tighter. But extending the analysis to long-term interest rates and comparing them with underlying economic conditions — growth and inflation — gives a different picture.

In the United States, 10-year Treasury yields hover around 4.1 per cent, while nominal GDP growth, combining roughly 2 per cent real growth and 2.5–3 per cent inflation, is higher. In other words, interest rates remain below nominal growth.

In the euro area, by contrast, interest rates exceed nominal growth. In Italy, for example, the IMF projects nominal growth of about 2.6–2.8 per cent over the coming years (roughly 2 per cent inflation plus 0.6–0.8 per cent real growth), while 10-year yields stand at 3.5 per cent. The same holds for France. Even in Germany the 2.7 per cent yield exceeds expected growth. Only in Spain and Greece does nominal growth surpass borrowing costs, creating relatively favourable conditions.

In short, once long-term conditions are considered, European monetary policy appears tighter than America’s.

This is consistent with the development of the respective central banks’ balance sheets. The ECB is now withdrawing liquidity from markets by allowing maturing government bonds to roll off its balance sheet, at an accelerating pace — nearly 600 billion euros per year, up from 400 billion a year ago.

The Federal Reserve, by contrast, has slowed the pace of quantitative tightening, from about 800 billion dollars to under 200 billion in the same period, while the Bank of England seems inclined to pause.

The divergence in central banks’ balance-sheet management and its differential impact on market liquidity appears to be one of the main drivers of the euro’s appreciation.

As successive ECB presidents have rightly stressed, the exchange rate is not a policy target. Yet it remains a crucial indicator of the relative stance of monetary policy.

A euro that keeps strengthening suggests that financial conditions may be tighter in Europe, with potentially damaging effects on an economy that is already weak.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.