Why Italy Stands Out as Europe’s Growth Laggard

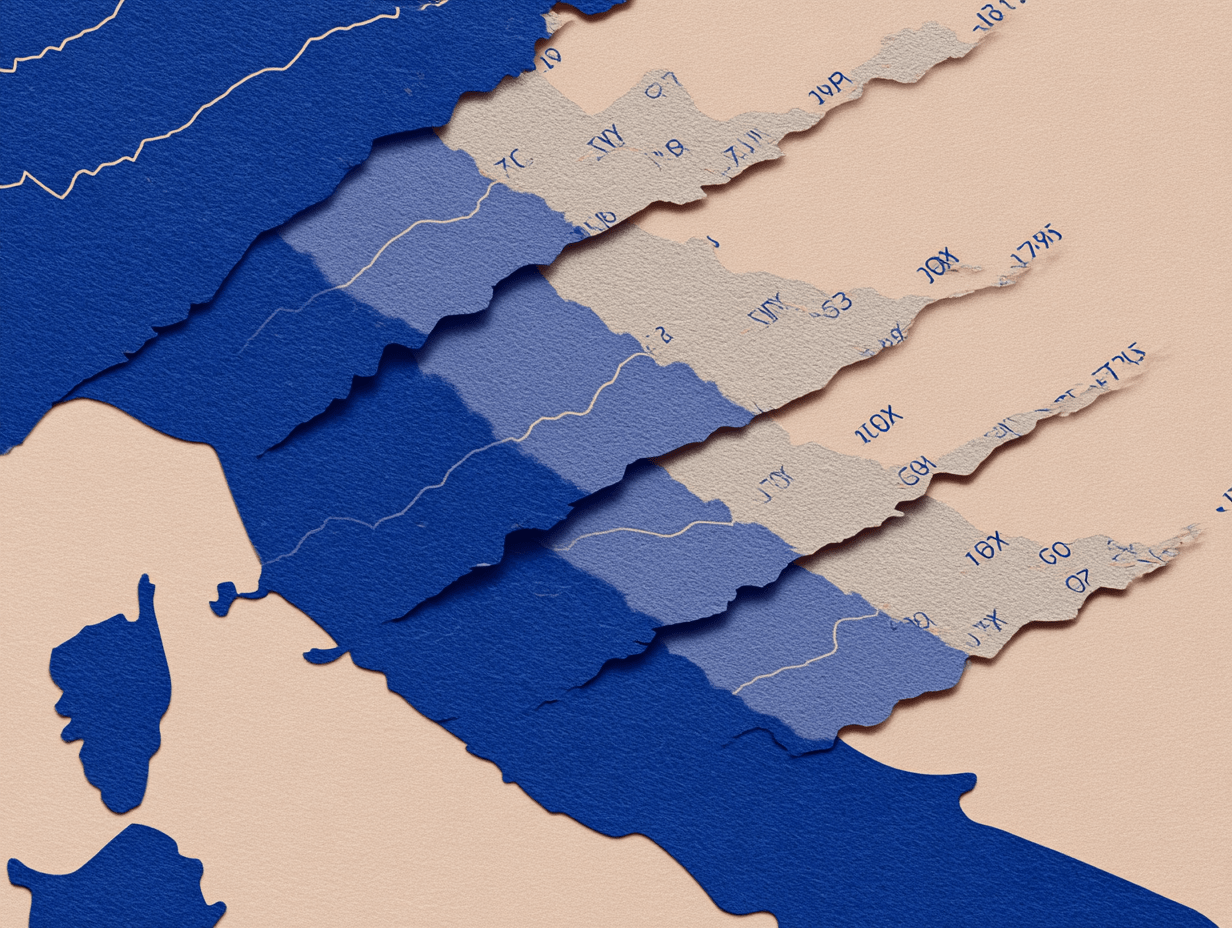

Italy’s economy is set to grow more slowly than almost all its eurozone peers in 2025, with only Austria, Finland and Germany posting weaker figures — although the latter are expected to recover in 2026. A commentary by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi

The latest forecasts from the European Commission suggest that, overall, the European economy is proving resilient in the face of geopolitical uncertainty. Growth this year is expected to reach 1.3 per cent, improving on 0.9 per cent last year and 0.5 per cent in 2023.

Over the next two years, the pace of expansion is expected to remain broadly unchanged. Beneath the surface, however, national trajectories diverge sharply.

Italy seems to be going in the opposite direction. Growth is expected to slow to 0.4 per cent in 2025, down from 0.7 per cent last year and 1 per cent in 2023.

Italy’s economy is now among the weakest performers in the eurozone, growing faster only than Austria, Finland, and Germany — all of which, however, are forecast to rebound in 2026.

Some commentators have sought to put these figures in a less discouraging perspective.

First, they point out that these are only forecasts, subject to wide margins of error and frequent revisions, sometimes even years later.

That is true. Yet the first three quarters of 2025 are now effectively known, with the latest showing almost zero growth. It is hard to imagine the fourth quarter altering the 0.4 per cent figure for the year in any meaningful way.

Moreover, past experience shows that both the European Commission and the IMF forecasts have often been overly optimistic for Italy and later revised downward.

A year ago, growth for 2025 was projected at 0.7 per cent; two years ago, at 1 per cent — an overestimate of 0.3 and 0.6 percentage points, respectively. The same pattern applied to 2024, which was initially forecast too high and was later cut back.

To reach the 0.8 per cent growth forecast for 2026, Italy’s economy would need to expand by about 0.2 per cent in each of the next five quarters — not impossible, but far from assured.

Another defence often advanced is that Italy has, overall, grown more than the European average since the Covid shock.

Indeed, between 2020 and 2025, Italy’s GDP rose by roughly 14 per cent, compared with 13 per cent for the euro area as a whole, 13 per cent for France, and just 4 per cent for Germany.

Yet this stronger performance largely reflects the post-pandemic rebound following a much deeper contraction in Italy in 2020 than in most other European countries.

Looking at a longer horizon — from 2018 to 2025 — Italy’s cumulative growth amounts to just 7 per cent, below the 9 per cent eurozone average.

Another explanation for Italy’s weaker growth is its declining population. Over the past four years, the population has contracted by about 0.1 per cent per year, and the decline is expected to continue.

Over the same period, the eurozone population as a whole has grown by an average of 0.4 per cent per year. Only the Baltic states and Greece have recorded a steeper demographic decline than Italy.

Measuring GDP per capita — by dividing output by the number of inhabitants — offers little reassurance. The sustainability of key financial parameters, such as public debt, is assessed against total GDP, not per capita income.

Moreover, population decline and ageing weigh directly on a country’s medium-term growth potential. As the population shrinks, so does the economy’s capacity to expand — even in per capita terms.

In Italy’s case, the demographic drag has been partly offset by a strong rise in employment in recent years, above the European average. Compared with October last year, the number of people in work has increased by roughly 225,000.

There remains significant scope to raise employment further and counter the negative effects of population decline. Even after rising by about four percentage points since before the pandemic — from 59 per cent to 63 per cent — Italy’s employment rate remains the lowest in Europe.

So far, most of the improvement has occurred among those aged between 50 and 64, largely as a result of past pension reforms. This also helps explain the recent decline in labour productivity, which has fallen by around 0.8 per cent per year over the past three years, and the weak growth in wages.

There is still wide room to improve female employment, which at 54 per cent remains well below the European average, as well as employment among the under 34, which actually declined over the past year to 50 per cent.

Achieving this would, however, require deep reforms of the labour market, the educational system, and social policies.

A true cultural revolution — for an ageing society.

A first version of this article was published in the Italian daily Il Foglio

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.