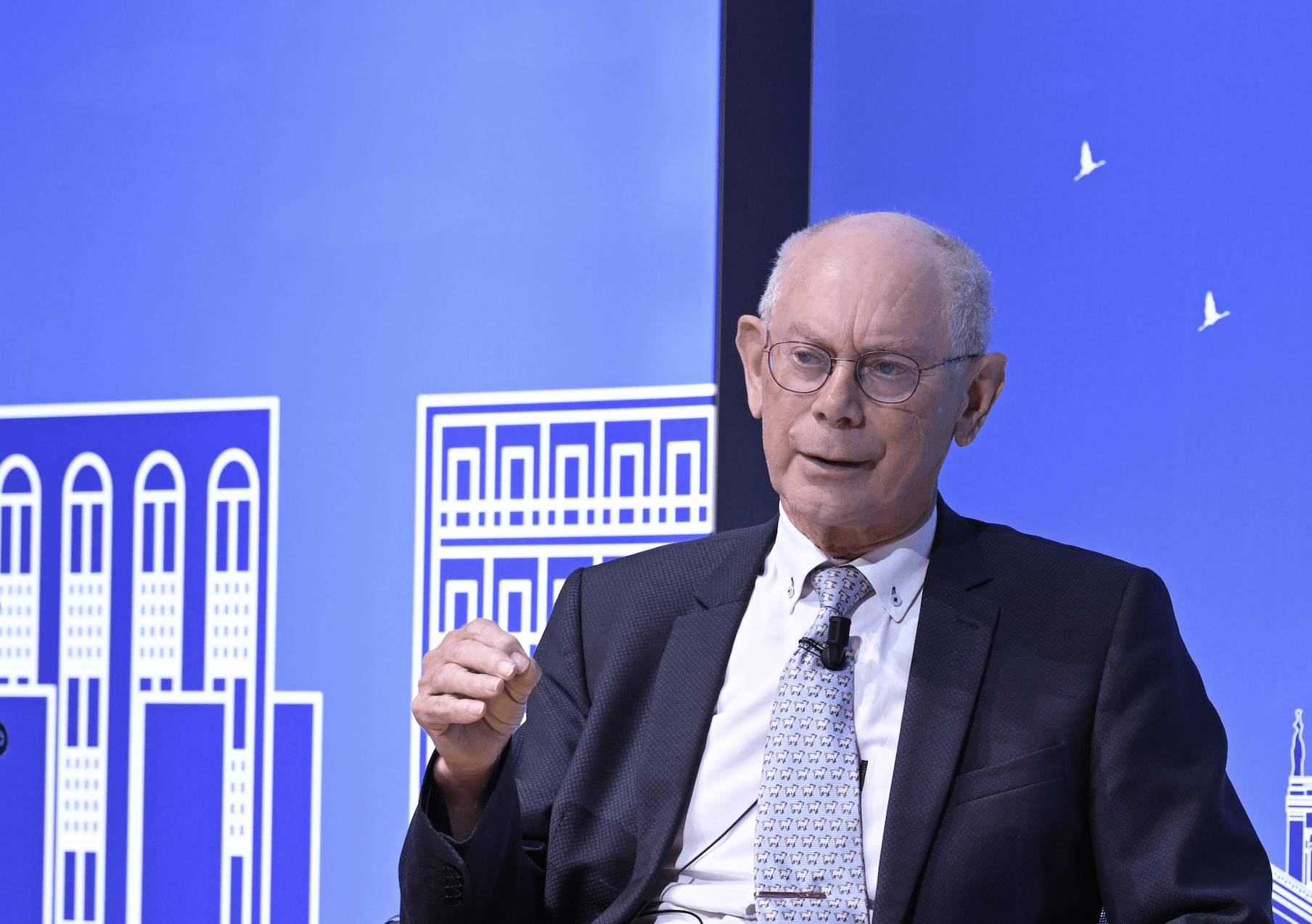

Why we Should Soften the Unanimity Rule in the European Council: an Interview with Herman van Rompuy

The first elected president of the European Council, Herman van Rompuy, discusses how to fix the decision-making process at the EU level

Building consensus remains the ultimate goal. That’s how the European Union functions. But if there’s genuine ill will, we shouldn’t be paralyzed,” says Herman van Rompuy, 76, one of the most respected consensus-builders in European Union politics.

A former Prime Minister of Belgium, Van Rompuy became the first elected President of the European Council on December 1, 2009, just in time to face one of the EU's most existential crises.

During his mandate, President Van Rompuy had to manage the risk of Greece leaving the euro, the potential collapse of the single currency, political turmoil in key Member States, notably Italy, and the unexpectedly prominent role of the European Central Bank under the leadership of Mario Draghi.

At the recent IEP@BU Annual Event, Is the EU Fit for a Fragmented World?, Herman Van Rompuy participated in a panel debate discussing how EU governance has evolved and how it must continue to adapt to current and future challenges. He also sat down for an interview with the IEP@BU website.

President Van Rompuy, how do you compare the current moment for the EU—particularly the European Council—with the time of your presidency?

This version enhances readability while maintaining the key points. Let me know if you'd like any further adjustments!

Let’s say that the Eurozone crisis was an exceptional crisis, it was a financial crisis, a monetary crisis, not comparable with the refugee crisis, the Covid crisis, or the war in Ukraine. It is difficult to make a comparison between those different crises.

My second remark is that in my time, during the first two and half years, we had a strong Franco-German cooperation, and that is missing today. That makes a lot of difference, of course.

The role of the president of the president of the European council is increased when there is no Franco-German understanding because he has to fill the gap. If he did not manage, we have a problem in the European Union institution.

So I worked in a very unstable environment, but with a very stable functioning of the European Council, due also to the very good cooperation I had with the president of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso, and to the Franco-German cooperation between the German chancellor Angela Merkel and French president Nicolas Sarkozy.

How was your approach to consensus building? The president of the European Council usually acts behind the scenes and we can see only the very final result of his dealmaking activity.

Since we need unanimity, because it is written in the treaty, you have to talk to everybody and treat everybody on an equal footing, even if you are working more closely, for instance, with France and Germany you should not create the feeling that all the others have to rally behind what is decided in Berlin or Paris.

That’s why I visited every European capital at least once a year: I was very close to every member State and to every member of the European Council. Respect for everybody and constant dialogue are very important ingredients for consensus building.

In his recent book Demagonia, Mario Monti revealed that both Italy and France had a "Plan B" in case the euro dissolved. They decided to keep this plan in the closet because, fortunately, together, you all managed to save the situation. Did the European Council and the Eurozone have a "Plan B" in case this effort failed?

We didn’t work with a formal "Plan B." There may have been intellectual exercises around a "Plan B," but that’s something entirely different.

Politically, I cannot imagine what kind of "Plan B" would have worked. But that’s behind us; it’s no longer an issue. I believe Mario Monti, by taking the lead and becoming Prime Minister of Italy, restored trust in Italy and played a significant role in that success.

But Italy couldn’t have been saved, right?

We couldn’t have saved Italy, the third-largest economy in the Eurozone. We could save Greece, Portugal, and Ireland, but not Italy, with its enormous public debt. So restoring confidence in Italian public finances was crucial. That’s where national politics played an essential role.

Don’t forget that the Eurozone and the European Union are also the sum of their member states. We discovered that with Greece. If Greece had left the Eurozone, it could have triggered a domino effect.

Was Grexit an actual risk?

During my time in office, we worked with the Greek government to restore confidence in the Eurozone and Greece. However, in 2015, after I left office, there was a second Greek crisis, which was very different.

In 2015, with the Syriza government in power, Greece could have left the Eurozone, but by then, it wouldn’t have impacted the rest of the Eurozone.

The key difference between those two periods was that by 2015, the institutional environment, especially with the ECB, had strengthened.

Moving to the current crises, what’s the best way to overcome the unanimity problem in international relations and geopolitical issues? Is there a way to move forward, such as with the German initiative on qualified majority voting? Or is this just part of how Europe works, and we have to deal with it?

First of all, when you look at the facts, we’ve reached unanimity on many issues—during the Covid crisis, for example, with the Recovery Fund and the common purchase of vaccines. It wasn’t easy, but we did it, and notably, without the Brits. Had the UK still been part of the EU, I’m sure we would never have had the €800 billion recovery fund.

In the Ukraine crisis, we’ve been unanimous, renewing sanctions every six months, which requires unanimity each time. So, we have achieved much more unanimity than people think.

Of course, it would be better to have a more flexible decision-making process, and in some areas, we do. For example, when deciding on tariffs on electric vehicles from China, we used a qualified majority, and the decision was made.

France is currently posing problems with the Mercosur agreement, but they likely won’t have a sufficient majority to block or cancel the agreement between the EU and Mercosur countries. We already have qualified majority voting on key issues. However, to change the rules more broadly, you need a treaty change.

Which many people think is almost impossible.

Good luck trying to change treaties in these times of high tension, both at the European and national level. Interestingly, according to Eurobarometer, public confidence in the EU remains relatively high. So, while a treaty change might be necessary, I’m not convinced about moving entirely from unanimity to qualified majority voting. There could be an intermediate solution—one where one or two countries cannot block the entire Union. My preference would be to soften the unanimity rule, so it’s not so strict, but without abandoning the goal of consensus.

Are you proposing to remove veto power but still aiming for the broadest consensus possible?

Exactly. Building consensus remains the ultimate goal. That’s how the European Union functions. But if there’s genuine ill will, we shouldn’t be paralyzed. During my time, we had to overcome the UK’s veto on the Fiscal Compact Treaty by switching to an intergovernmental agreement—a "coalition of the willing." In that case, 27 out of 28 member states agreed.

Now I’ve heard that to circumvent Hungary blocking the European Peace Facility, the High Representative is considering a similar coalition of the willing, where willing member states contribute freely. We have to be creative and imaginative, especially when treaty change isn’t an option.

While a treaty change might be necessary, I’m not convinced about moving entirely from unanimity to qualified majority voting. There could be an intermediate solution—one where one or two countries cannot block the entire Union

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.