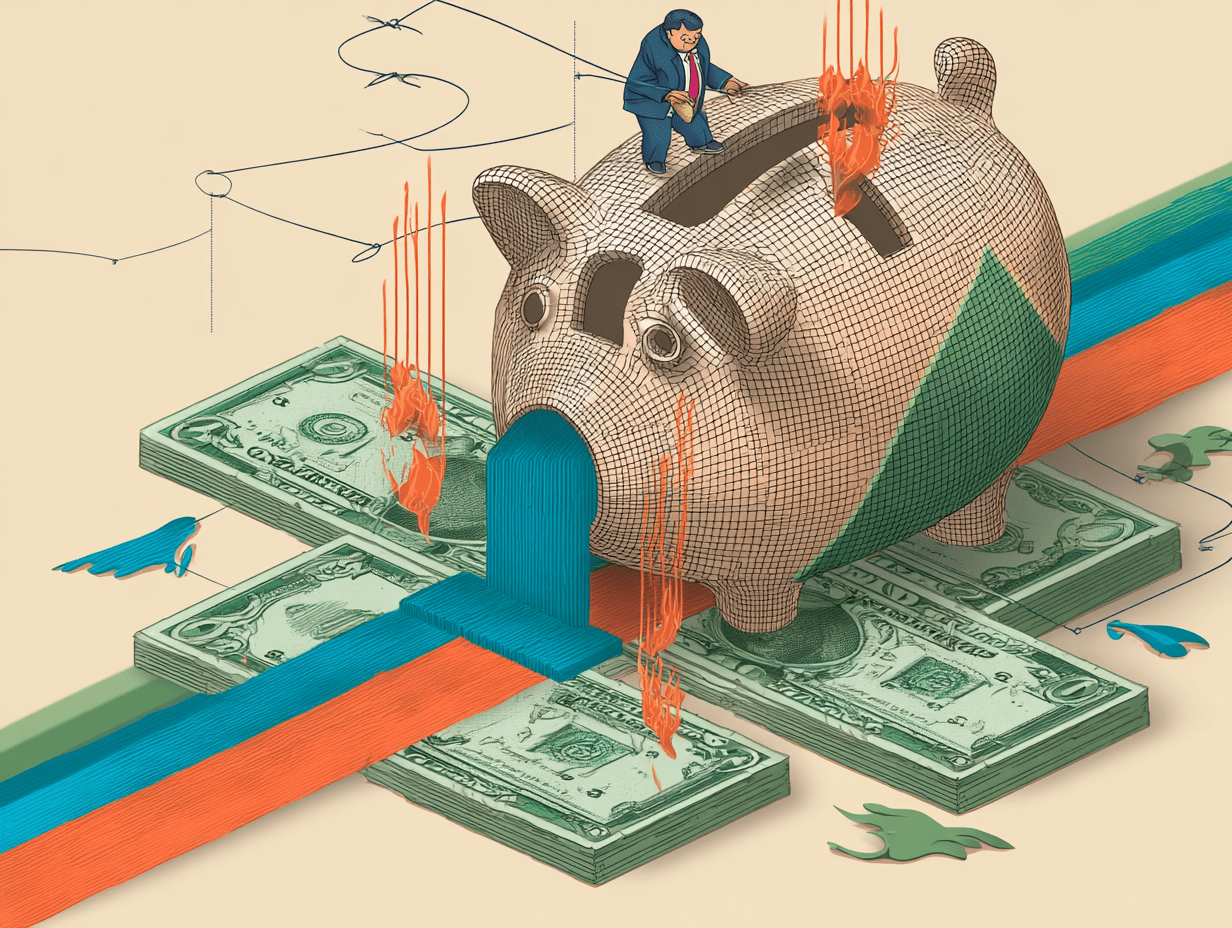

Why Windfall Taxes on Banks Backfire

Italy’s recurring debate on “extra-profits” misses the point — such levies weaken lending and harm the wider economy. A commentary by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi

Extraordinary taxation of profits or buybacks reduces bank profitability, raises banks’ cost of capital, and creates a distortion compared with other sectors.

Each year, as Italy prepares its budget law, various proposals surface to raise additional tax revenues. One idea that has gained traction in recent years is a levy on banks’ so-called “windfall profits.”

This tax is usually justified with two arguments. The first is that banks’ profits have recently risen to exceptionally high level, thanks to the increase in interest rates decided by the European Central Bank to curb inflation. Such profits, it is claimed, are unearned windfalls generated by exogenous factors.

The second argument is that banks benefit from an implicit state guarantee, since governments intervene to rescue them in times of crisis. In exchange for this guarantee, it is said to be fair to tax banks when their profits are high.

Both arguments are unfounded.

To begin with, objective criteria are needed to define when a profit is “extraordinary” rather than “ordinary.”

Profitability is generally measured by return on equity (RoE). Among the 20 largest Italian listed companies in 2024, the average RoE was 15.25 per cent. The six banks in this group posted an average of 15.56 per cent, while the other 14 non-financial firms reported 15.12 per cent. Median profitability was 13.25 per cent in banking, against 13.34 per cent for the rest.

These figures show that bank profitability has been broadly in line with other Italian companies. Banks have not made excess profits.

Certainly, bank profitability has improved compared with a few years ago. In 2022, the six largest listed banks had an average RoE of 11.5 per cent, well below the 16.9 per cent of other major firms. The recent recovery is simply a return to levels comparable with the rest of the corporate sector, after years of relatively weak bank earnings in Europe.

A more precise analysis would compare profitability not just across sectors, but against the cost of equity — the minimum return companies must deliver to compensate shareholders for their investment.

In banking, the cost of equity is higher than in most other sectors, particularly in Europe, due to prevailing regulatory and fiscal uncertainty. This reinforces the conclusion that recent bank profitability, while improved, is not abnormal.

As for public guarantees, it is important to recall that since 2014, with the creation of the European Banking Union, large banks have contributed annually to the Single Resolution Fund, designed to recapitalise institutions without recourse to public money.

Beyond the weak justifications, the more fundamental problem with a windfall tax on banks is its effect on lending and on the economy as a whole.

Some policymakers hope that taxing bank profits, or share buybacks, will push banks to distribute fewer dividends and instead lend more to households and firms.

There is indeed a direct relationship in banking between the size of the balance sheet and the available capital. The greater the capital a bank holds above regulatory minimums, the more its balance sheet can expand — and the more loans it can provide.

Yet this expansion depends on one crucial condition, often overlooked by regulators, academics, and policymakers alike: bank lending must be sufficiently profitable to cover the cost of capital.

If profitability is too low, banks tend to shrink their balance sheets and return excess capital to shareholders.

Extraordinary taxation of profits or buybacks makes the problem even worse. It reduces bank profitability, raises banks’ cost of capital, and creates a distortion compared with other sectors. The unintended consequence is that banks increase dividend payouts — sometimes to 100 per cent of earnings — while reducing balance sheet growth and loan supply.

In other words, the more dividends are taxed, the greater the incentive for banks to contract activity and cut credit to households and businesses. That is hardly what the economy needs right now.

A first version of this article was published in the Italian daily Il Foglio

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.