Big Budget, Old Habits?

Funding Innovation in Europe with the Next Framework Programme: a commentary by Daniel Gros, and Giorgio Presidente

The Commission has published its proposal for the EU budget covering the years 2028–2034, with a total envelope of about €2 trillion in expenditure, of which €175 billion is destined for the next Framework Programme (FP) for research and innovation. This amount is almost double the roughly €100 billion allocated to the current FP, called Horizon Europe.

This piece reviews some key strengths and concerns with the Commission’s proposal and puts them in relation to recent analyses of the European innovation ecosystem.

Still, the Emphasis on Collaborative Projects

Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of the proposal is the continued emphasis on Pillar II, now renamed the Competitiveness and Society Pillar. Funding from this pillar requires applicants to form consortia across multiple EU member states. Consortia, often involving 20 or more participants, are cumbersome to manage and difficult to evaluate ex ante.

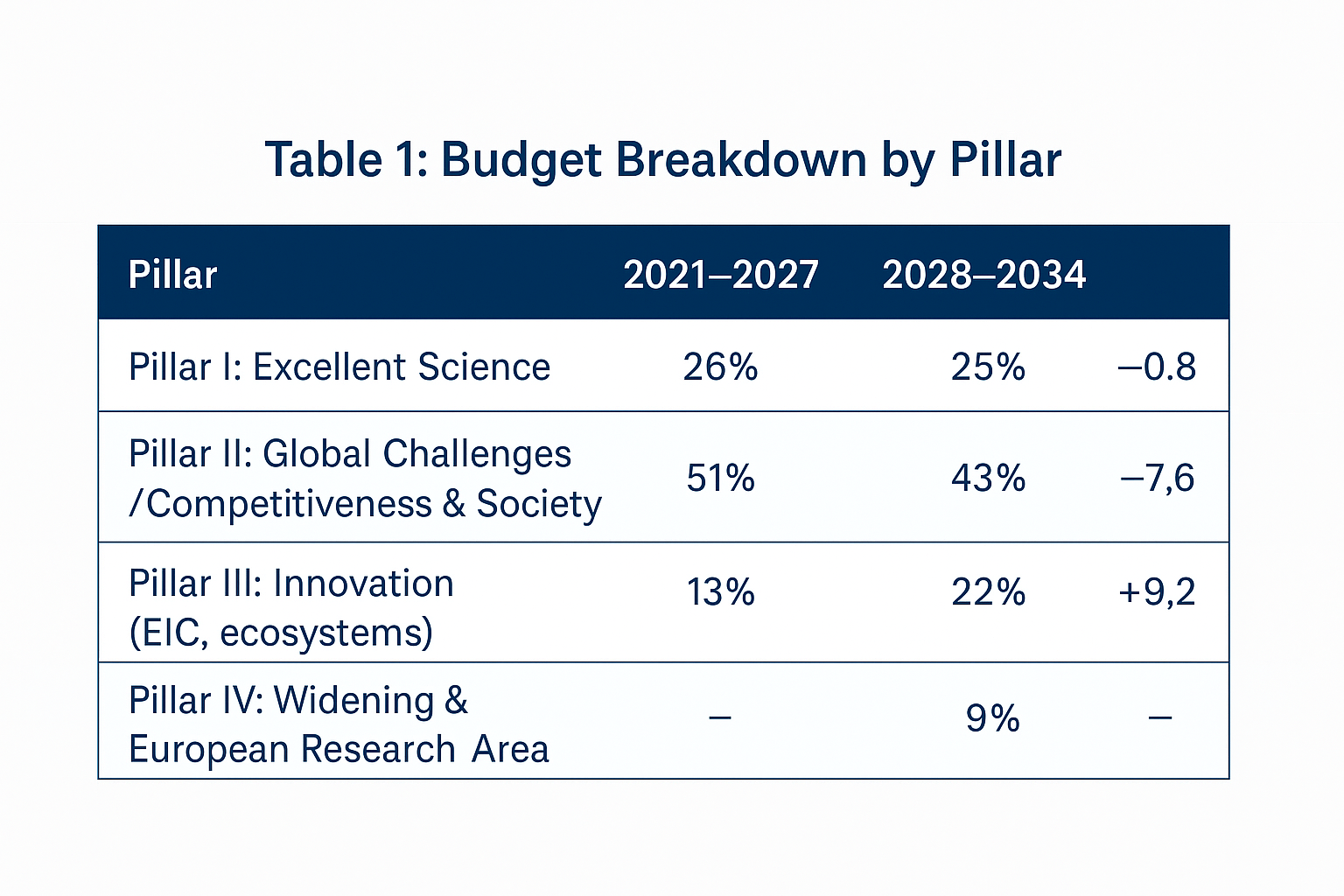

Despite a modest drop in its share of the overall budget (see Table 1), Pillar II remains the largest component, accounting for over €75 billion.

What Value for Money Does Pillar II Deliver?

The recent Horizon Europe interim evaluation report devotes only a single paragraph to evaluating Pillar II. It states that “scientific excellence is a primary evaluation criterion,” yet only 3,026 peer-reviewed publications were reported.

Given that €25 billion had been disbursed at the time, each publication effectively cost €8 million. While some papers may have immense value, this average is strikingly high—especially when compared to European Research Council (ERC) grants under Pillar I, which typically cost less than €2.5 million per project and yield multiple top-publications. Pillar I remains the true engine of scientific excellence.

If the added value of Pillar II lies in bringing science closer to the market, the patenting record provides little reassurance. The evaluation cites only 24 Intellectual Property Rights applications, such as patents and trademarks, and 1,900 “innovative outputs”, with no clarity on what these outputs are, how they are measured, or whether they lead to tangible economic returns.

The record of Pillar II in delivering excellent science is thus not encouraging. Moreover, as argued in the recent report Funding Ideas, Not Companies, raising R&D spending should not be an end in itself. What matters is not just how much is spent, but how it is spent. The report finds that Pillar II yields no lasting impact for the enterprises it finances.

This continued prioritization of collaborative projects is thus puzzling. There is, to date, no compelling evidence of their effectiveness. On the contrary, Funding Ideas, Not Companies presents empirical findings that cast serious doubt on the impact of collaborative instruments.

Funding Innovation from the Bottom Up

One positive reform concerns how future calls for proposals will be structured. At present, the calls for proposals under Pillar II are very detailed and prescriptive, thus limiting the potential for finding pathbreaking ideas.

The Commission now proposes to have less prescriptive calls, with open topics by default, allowing applicants more flexibility in charting pathways to impact. These recommendations were central in Funding Ideas, Not Companies, and, if implemented effectively, could foster more bottom-up innovation.

Big, Beautiful EIC

Table 1 shows a welcome shift toward Pillar III, particularly the European Innovation Council (EIC), which is expected to nearly double in size.

This is encouraging because the evidence in our report suggests that the EIC instrument devoted to SMEs is effective in boosting the long-run growth of beneficiaries (consistent with another recent study). Therefore, the budget expansion of the EIC aligns with the overarching objective of boosting competitiveness in the EU.

The global gold standard in support for innovation is the famous DARPA, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which has spearheaded transformative technologies from the internet to GPS and autonomous vehicles.

Its approach has since been replicated beyond defense, giving rise to other ARPA-style institutions such as ARPA-E for energy, IARPA for intelligence, and the newly established ARPA-H for health

Indeed, the Commission proposes that the EIC will incorporate more “ARPA” elements—such as stage-gated support for high-risk projects, and the possibility of terminating underperforming ones—under the guidance of expert Programme Managers.

A joint report by Bocconi, the ifo Institute, and Toulouse School of Economics from 2024 highlighted the potential of EIC programmes, particularly those modeled on ARPA-style agencies in the United States, to help Europe escape its Middle Technology Trap.

Budget Isn’t Everything

Unfortunately, a critical limitation remains: staffing. While ARPA agencies like DARPA operate with hundreds of programme managers, the EIC currently has just ten. This not only overstretches existing staff but also limits the diversity and depth of technical expertise.

Without a significant increase in qualified programme managers, the EIC cannot scale effectively. Worryingly, the Commission’s proposal is silent on this point.

The Commission also proposes accelerated funding timelines. Yet the reduction in time-to-grant from 8–9 months to 7 months seems modest. For comparison, DARPA’s time-to-grant typically ranges from 3 to 6 months—highlighting the need for much bolder streamlining if the EIC is to compete globally.

Conclusions

In summary, while the Commission’s MFF proposal is a step forward—especially with more funding for the European Innovation Council and less prescriptive calls—its focus on large, complex collaborative projects risks limiting impact.

The real opportunity to reshape the programme lies with the European Council and Parliament during negotiations. More money should also be spent more wisely.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.