Biodiversity COP 16: Where EU Member States Stand on National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans

The 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 16) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), or "Biodiversity COP 16", will take place in Cali, Colombia, from October 21 to November 1.

The 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 16) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), or "Biodiversity COP 16", will take place in Cali, Colombia, from October 21 to November 1. The CBD is an international treaty that was signed by 150 government leaders at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 (which also led to the more well-known "Climate COPs") to reverse the alarming decline in biodiversity around the world. The CBD Treaty, now ratified by 196 parties, serves as an international legal framework for biodiversity protection with three objectives: the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of the components of biodiversity, and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of genetic resources.

The previous "Biodiversity COP 15", which took place in Montreal, Canada, in December 2022, was particularly important as it led to the adoption of the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which provides a new plan aimed at “halting and reversing biodiversity loss by 2030” and “restore harmony with nature” by 2050. To accomplish these goals, the GBF specifies 23 specific targets to guide the actions of the global community, including: protecting 30% of land and oceans by 2030 (GBF Target 3); reducing the risks from the use of pesticides (GBF Target 7); reducing harmful subsidies by $500bn by 2030 (GBF Target 18); mobilizing at least $200bn per year for biodiversity by 2030, including at least $30bn through international finance (GBF Target 19).

The importance of NBSAPs

Ahead of the forthcoming "Biodiversity COP 16", countries are expected to release their National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) for the 2022-2030 period. The purpose of NBSAPs is to transcribe countries' commitment to the international targets mentioned above into actionable sectoral and cross-sectoral plans, programs and policies at the national level. NBSAPs therefore offer valuable insights into the future of the biodiversity conservation policy landscape and allow for the creation of effective accountability mechanisms.

While past NBSAPs have been crucial in raising the profile of the CBD agenda, it is important to acknowledge that their application has been limited. In fact, none of the targets that had been adopted in the international framework prior to the GBF (the so-called "Aichi Biodiversity Targets" covered the 2011-2020 period) have been reached. Moreover, as of October 1st, only 25 out of the anticipated 196 NBSAPs have been published.

Analyzing EU NBSAPs

The European Union (EU) stands out for having submitted 10 out of the 25 NBSAPs (as of October 1st) ahead of "Biodiversity COP 16". In addition to the general EU NBSAP (the EU must publish an NBSAP as a signing party to the Convention) nine countries—France, Spain, Austria, Hungary, Luxembourg, Ireland, Malta, Slovenia, and Italy—have also published their biodiversity plans. Their content offers us a crucial insight into Europe’s priorities in terms of biodiversity commitments and perspectives ahead of the conference.

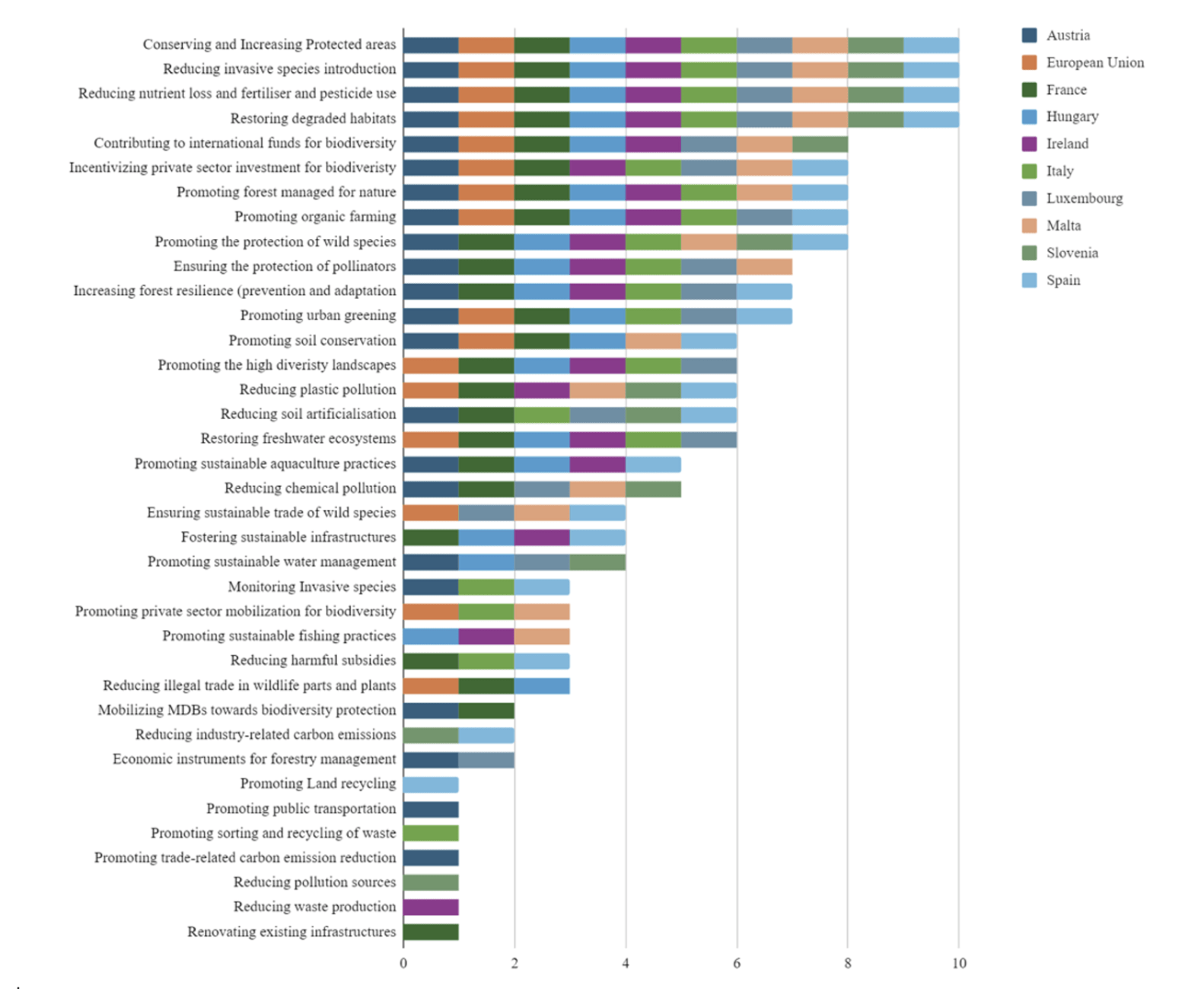

Our ongoing analysis of EU NBSAPs (as part of the Coalition for Capacity on Climate Action – C3A – program) identifies 37 biodiversity conservation and protection policies and initiatives (Figure 1). Four of them are present in all NBSAPs submitted by EU members so far: efforts to conserve and expand protected areas; the reduction of invasive species introduction; the reduction of nutrient loss and of fertilizer and pesticide use; and the restoration of degraded habitats. For example, France’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) aims to place 5% of its metropolitan waters under strict legal protection. Similarly, Ireland has committed to reducing the introduction of invasive species by updating its national legislation to better address the management of aquatic invasive species.

With regards to the economic sectors concerned by such policies, we find that that the EU NBSAPs primarily concerns the agricultural sector (concerned by policies such as the reduction of pesticides or the support for organic farming) but also other sectors such as manufacturing and real estate activities, thereby reflecting the need to integrate biodiversity-related considerations into all economic activities. Starting to systematically track countries’ strategies and action plans to reverse biodiversity loss will enable, in the future, to monitor how much was effectively implemented by different countries.

Figure 1: Occurrence of biodiversity policy listed in EU NBSAPs

Source: authors, based on NBSAPs submitted ahead of “Biodiversity COP 16” (as of 1 October 2024)

The need for harmonized NBSAPs

Our analysis also highlights notable gaps that remain to be addressed. This concerns particularly the lack of detailed financial needs (even though broad or even vague commitments to increasing public and private finance are often mentioned) and the limited amount of details explaining how concretely harmful subsidies will be reduced (as per GBF Target 18), the latter being addressed in only 3 of the 10 EU NBSAPs studied.

Additionally, the absence of a standardized structure for NBSAPs, even at the EU level, combined with a lack and inconsistency in the indicators and targets, complicates efforts to assess progress, ensure accountability, make reliable forecasts, and coordinate action at the supra-national level. This highlights the importance of calling for a better homogenization of NBSAPs, as well as for a systematic use of indicators and targets at the EU level and internationally.

However, promising initiatives are emerging to track the commitment of countries to GBF targets through their NBSAPs, such as the recent development of tracking tools developed by Carbon Brief, the WWF and the CBD. Improving such reporting can enable greater civil society scrutiny as well as facilitate future academic research on the application of diverse biodiversity policy strategies. This could only contribute to global efforts to achieve the Kunming-Montreal targets, taking humanity one step closer to “restor[ing] harmony with nature."

The authors all contribute to the Nature Transition Hub of the Coalition for Capacity on Climate Action (C3A), a knowledge-exchange and capacity-building program for Ministries of Finance that is funded and hosted by The World Bank. See: https://www.climatecapacitycoalition.org/

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.