The Changing Stance of the EU Toward Israel

Ursula Von der Leyen calls for a tougher stance on Israel, forcing the Council to weigh economic ties against the Union’s principles. A commentary by Giorgio Presidente

Since October 2023, the war between Israel and Hamas has become one of the most devastating phases of the long-standing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Political deadlock persists, and diplomatic efforts have so far failed to secure either a ceasefire or a credible path toward peace.

On September 10, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced for the first time that Brussels would propose a package of measures against Israel “to carve out a way forward”. The plan includes a freeze of bilateral support, a halt to payments, sanctions on extremist ministers and violent settlers.

The following day, the European Parliament approved a resolution calling on EU member states to “consider recognizing the State of Palestine, with a view to achieving the two-state solution”.

The EU has long been cautious in its stance toward Israel, reflecting both strategic partnerships and internal divisions.

The EU–Israel Association Agreement anchors political dialogue, economic cooperation, and trade liberalization, granting Israel preferential access to the single market while the EU benefits from Israel’s advanced technology and research base.

In 2024, trade in goods between the EU and Israel reached €42.6 billion, with the EU as Israel’s largest trading partner, accounting for roughly a third of its total trade. Relations also cover intelligence and counter-terrorism. For many member states, supporting Israel’s security is seen as both a strategic and moral responsibility.

This context has led the Commission to emphasize humanitarian access and adherence to international law while avoiding explicit criticism.

Internal divisions reinforced this caution: while countries such as Ireland, Spain, and Belgium pushed for tougher positions, others resisted, leaving Brussels to adopt consensus language that preserved unity but downplayed criticism.

Public opinion, however, is shifting.

The humanitarian devastation in Gaza has generated mass protests, civil society campaigns, and mounting frustration with both Israel’s conduct and the EU’s perceived passivity. Opinion polls show signs of rising disapproval of the EU’s cautious stance.

The UN Special Rapporteur’s widely cited report, describing Israel’s actions as an “economy of genocide” in which corporate and research actors—including European ones—play a role, further fueled these concerns.

A growing number of eminent academics from Europe and the United States have signed a letter to Israel’s Prime Minister, emphasizing that due to potential European sanctions, debt downgrades, professional emigration, and a high-tech exodus threaten to cripple Israel’s economy itself.

Large institutional investors are already withdrawing their investments: for example, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund has recently sold its shares in Israeli companies.

Pressure has also emerged from within the policy community.

In a recent open letter, 209 former EU and member state ambassadors and senior officials urged tougher measures.

One involves trade restrictions: barring Israeli defense firms from benefiting from Security Action for Europe (SAFE), a €150 billion procurement instrument, and potentially suspending or terminating the Association Agreement, which contains a human rights clause making respect for democratic principles an “essential element” of the partnership.

Another involves cutting EU research funding to Israeli entities implicated in violations. The measure would carry weight.

What’s in for the EU?

The costs of a tougher line are significant. The EU would risk curtailing access to Israeli advances in frontier fields like artificial intelligence and aerospace, both critical to Europe’s bid to overcome its “mid-tech trap”.

Efficiency losses resulting from decoupling from Israel’s innovation ecosystem could be at least partially offset by budget-neutral reforms that redirect research and innovation funding toward the most effective programs—particularly those that support small and independent firms—where the impact of EU support is highest but current budgets are limited.

A tougher stance could also provoke political and economic retaliation from the United States, Israel’s closest ally. For example, despite the conclusion of a trade agreement with the EU, President Donald Trump could still impose new tariffs.

Any strain on transatlantic relations would be especially problematic at a time when the EU depends heavily on U.S. cooperation in security, technology, and global diplomacy.

At the same time, the costs of a firmer stance would be offset by showing responsiveness to public opinion, strengthening the EU’s credibility as a defender of humanitarian norms, and positioning Europe as a balanced mediator in the Global South and Arab world, where its influence has diminished. It could also expand diplomatic leverage, foster trust among emerging powers, and strengthen the EU’s claim to strategic autonomy.

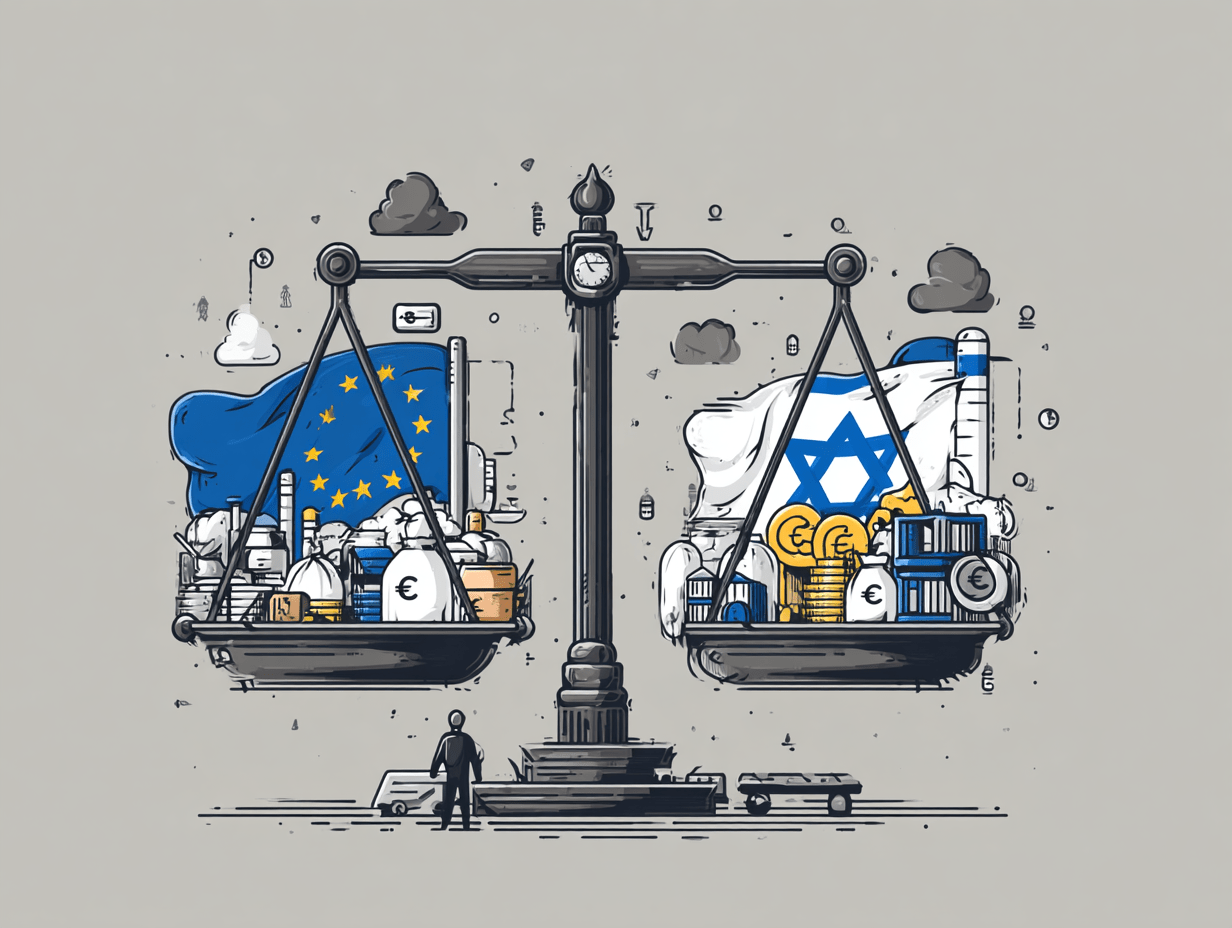

The choice for the EU thus involves a trade-off. Preserving close ties with Israel maintains economic benefits and access to advanced technology, but risks alienating citizens and undermining the EU’s self-image as a principled actor.

The Commission’s concrete proposals on this matter remain to be seen. Ultimately, the Council’s choices will reveal the kind of Europe it seeks to project: either a pragmatic actor constrained by alliances and economic ties, or one prepared to uphold its declared values even at significant cost.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.