The Double Majority Problem Is Weakening the EU

For the first time, the EPP can forge shifting coalitions with partners whose visions for Europe are fundamentally at odds—paralysing policy-making and exposing the Union’s underlying fragility. A commentary by Marco Buti, and Marcello Messori

For the first time in the history of the European Union, its strongest party—the European People’s Party (EPP)—enjoys a structural advantage that risks turning into a major liability.

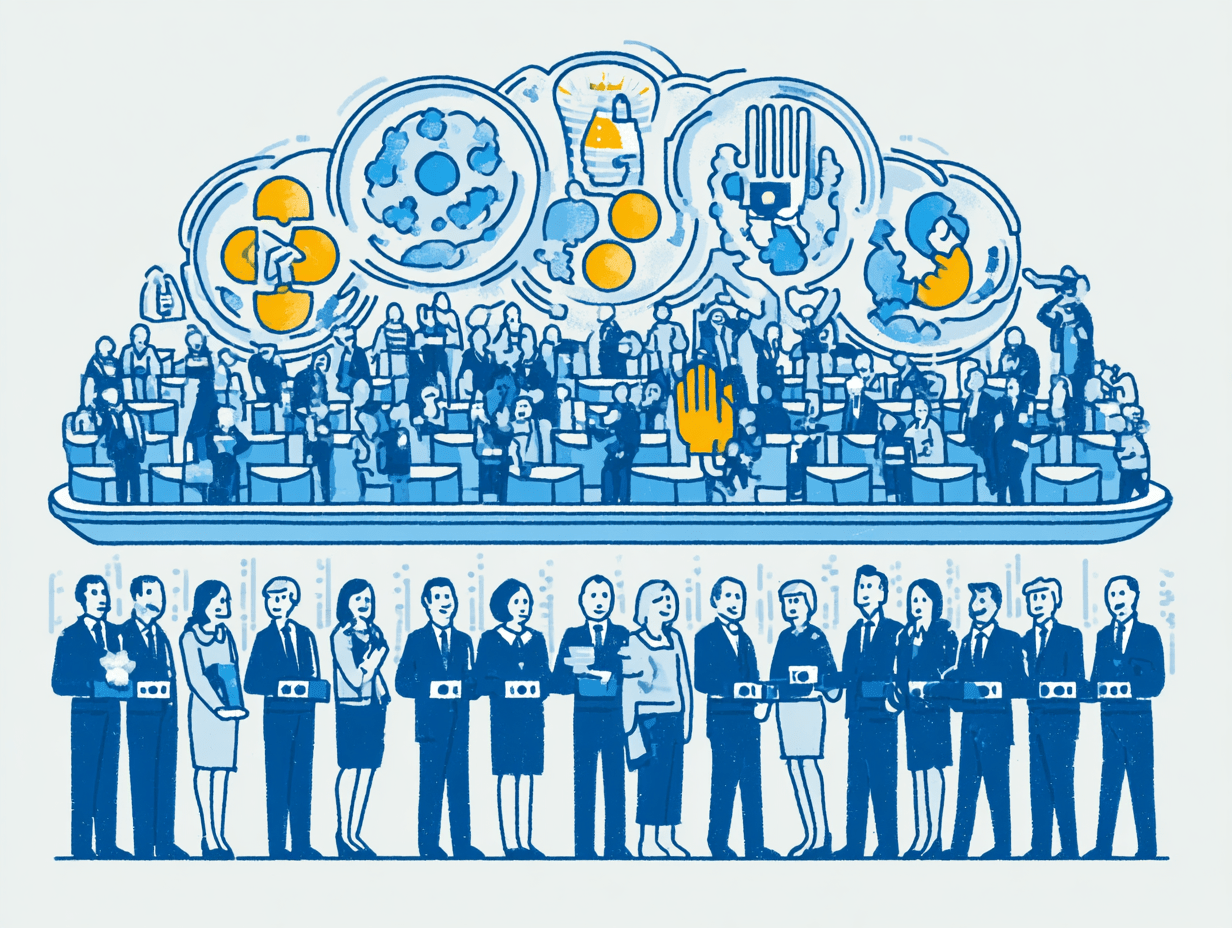

The EPP now has access to two rival majorities in the European Parliament: one formed with socialists, liberals, and (in a more marginal role) the Greens, and a second that leans to the right and far right.

In recent months, this “double oven” (to borrow an old Italian political metaphor) has profoundly shaped parliamentary business.

EPP leader Manfred Weber has not hesitated to use votes from the right and far right to block the green transition, accelerate deregulation, and toughen immigration policy.

These moves have faced only lukewarm resistance from centre-left parties, who are themselves riven by deep internal divisions on crucial EU issues.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Party of European Socialists (PES), where there are major disagreements over common defence policy.

Even within national delegations, conflict abounds: socialists from Eastern and Northern Europe generally support increased defence spending, while those from Southern Europe are often opposed or split.

This internal fragmentation within the PES only strengthens the EPP’s hand, providing more opportunities to ally with the right.

To make matters worse, Members of the European Parliament today are more answerable than ever to their national leaders—leaders who are themselves grappling with domestic weakness, as illustrated by Emmanuel Macron in France and Pedro Sánchez in Spain.

These national fractures reverberate in the European Parliament, resulting in increasingly erratic voting patterns.

The outcome is an unstable system where the possibility of alternative majorities and the breakdown of trust among pro-European parties make it almost impossible to pass coherent policy packages.

In the past, such packages allowed each group to see its priorities addressed through credible, time-based commitments.

Today, victories and defeats are measured vote by vote, because no one dares bet on the future loyalty of any ad hoc coalition.

The threats by socialists and liberals to “exit the majority” are little more than bluffs: the European Parliament simply does not operate like national legislatures.

Conversely, proposals to extend the power of legislative initiative to the Parliament—currently reserved for the Commission—risk multiplying tensions and deepening division.

Some might hope that the weaknesses of the Parliament are offset by stronger leadership in the Commission or, by extension, in the European Council. But reality is less reassuring.

As we argued when the new Commission was formed, most commissioners lack real authority and, rather than exercising their executive power towards their parliamentary groups, often act simply as spokespersons for their home countries.

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen may wield considerable influence within her College, but the low profile of most portfolios weakens not just the Commission as an institution, but also her own presidency.

Von der Leyen herself suffers from a similar dependency as many commissioners: her decisions too often remain subordinate to the priorities of the German government.

Rather than consolidating the alliance with the pro-European parties that supported its formation, the Commission and its president have instead largely aligned with the EPP—by far the dominant force among commissioners.

In the European Council, the predominance of EPP-affiliated heads of government is equally, if not more, marked. The socialist president of the Council, António Costa, has been reduced to an almost ghostly figure.

How to break the deadlock

Is there a path to revitalising a pro-European coalition? There are, in our view, three, though all are precarious.

The first is a matter of self-interest: if German Chancellor Friedrich Merz wants to avoid surrendering power to the far right at home, he cannot legitimise the AfD’s role in Europe by allowing it to become a structural partner of the EPP.

The second depends on the outcome of the Dutch elections in October: if the progressive coalition led by Frans Timmermans prevails, the balance within the European Council could begin to shift.

These two factors could create space for a third, more strategic prospect: the recognition that only a restoration of the old pro-European majority can allow the EU to meet the profound challenges of our time, from geopolitical conflict to technological lag and the threat of another Trump presidency.

In such a dramatic international scenario, the Commission must fundamentally rethink the EU’s relationship with the United States and the wider world, and reorganise its own institutional structure to achieve true European strategic autonomy.

One thing is clear: this outcome cannot be achieved in partnership with anti-European right-wing forces. The recent no-confidence motion against the Commission, promoted by those very groups—even if it failed—serves as a stark reminder of the risks involved.

A version of this article originally appeared in Il Sole 24 Ore.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.