EU’s Climate Leadership – Is it Time to Rethink our Policy Toolbox?

As the EU’s climate plans hit political limits, more direct industrial policies could offer a way forward. A commentary by J.Christopher Proctor, and Romain Svartzman

November was not easy on the EU’s climate ambitions. In the leadup to the 30th conference of the parties (COP 30) in Belém, Brazil, the UN Environment Program (UNEP) released its annual Gap Report which found that the world was on track to warm 2.8°C under current policies, leaving a substantial ‘gap’ between existing efforts and the international commitment to keep warming to 2, and if possible 1.5°C. This projection came just weeks after the World Meteorological Organization announced that the atmosphere’s carbon dioxide concentration had grown by a record amount in 2024.

With the global failure in clear view, COP 30 was an opportunity for the EU double down on its own transition to net-zero and take a leading role in facilitating an international response. Instead, in fight after fight the block bent to pressures to weaken its agenda, losing ground and authority with which to lead.

Losing ground

In the hours before delegates were due to arrive in Belém, the European Council agreed to a set of amendments to the European Climate Law in order to “reflect concerns about the EU’s competitiveness” and provide additional flexibility for member states. Most notably, this included a change to the EU’s existing target of 90% emission reductions by 2040 (from a 1990 baseline) to now allow for 5% to come from international credits representing carbon reductions outside of the EU.

As this 5% refers to the emissions reductions since 1990, which have already fallen substantially, the difference between domestic EU emissions in 2040 with and without the rule change could be as high as 50%. The 90% target itself was already on the low end of the 90-95% recommended by the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change.

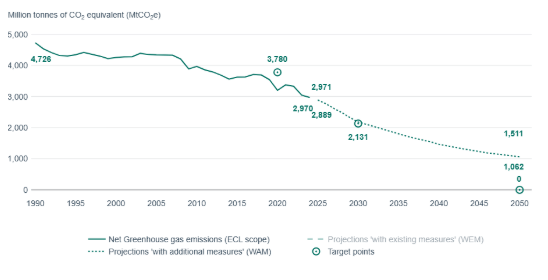

Neither target is on track to be met according to projections from the European Environmental Agency. Even when considering policy measures which have been announced but not yet enacted (“additional measures” in the graph below), the EU is on pace to double the new 85% limit and triple the previous 90% limit by 2040.

Emission projections for the EU-27 from the European Environmental Agency

Simultaneously with the change in the Climate Law, the Council and Parliament agreed to delay the expansion of the ETS to cover buildings and transport (the so-called ETS2) for a year, to 2028. The sectors covered by the ETS2 represent over 40% of the EU’s total emissions, roughly the same size as the amount of emissions covered by the existing ETS.

On its commitments to finance climate mitigation and adaptation in developing countries at the COP itself, there was no clear progress from the EU, despite the presentation during the COP of a detailed Baku to Belem Roadmap to 1.3T report, which outlined options for achieving the ambitious, yet unachieved, international financing targets.

Worse, during the negotiations, the German government released a draft 2026 budget which “slashed” 1.5 billion euros from its climate development financing program.

The EU took a further diplomatic hit during the event, as “unilateral trade measures” emerged as one of the major themes of the conference due to the impending implementation of the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which will penalize the EU’s trading partners that do not sufficiently price carbon.

Apart from the activity surrounding the COP, even relatively light-touch disclosure requirements came under fire, with the EU parliament voting to exempt all but the largest companies from new reporting requirements on human rights and environmental impacts of their activities and their supply chains.

Finally, to close out a very long November, the parliament voted to once again delay the implementation of the EU’s deforestation law. The measure, which would set up a system to verify that wood products used in the EU are not being sourced from deforested land, was set to go into effect at the end of 2025, but will now enter a period of review. The law, adopted in 2023, was similarly delayed at the end of last year.

A way forward?

November’s policy retreats have led to a less ambitious transition at home and less influence on climate abroad. Could a change of policy tools get the EU moving in the right direction?

Rather than relying mostly on approaches where policymakers set the stage (e.g., through the ETS or CBAM) while letting market participants adjust, another way forward would be to prioritize concrete investments into sectors, and even projects, which will facilitate the transition.

Public investments in large-scale infrastructure like electricity grid expansion or high-speed rail, or subsidies for activities like insulating buildings, could more directly build support for the transition with business and citizens, not the least because they enable energy savings while building up energy sovereignty.

If coordinated at a European level, this more direct policy approach also provides an opportunity to address structural geographical imbalances, and could be facilitated by the EU institutions through common borrowing for an investment fund and by an ongoing shift in national fiscal rules.

As an example, the EU’s Clean Industrial Deal, a new initiative which seeks to alleviate issues faced by energy-intensive industries and the clean-tech sector in Europe, could be turbocharged with public funds for research and development and for the public procurement of carbon-neutral products.

While a unified approach is certainly beneficial, unilateral action at the national level is also possible.

For instance, in one of the rare steps forward in the current landscape, Germany's government has recently agreed on a debt-financed special fund worth 500 billion euros for a wide range of infrastructure and climate-related projects for the next decade.

Initiatives like this, where politically possible, could go a long way towards building the momentum needed to eliminate net-emissions by 2050 within the EU.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.