The Representation Gap Weakening Germany's Traditional Left

The September 2024 state elections in Germany mark a low point in public support for the governing left-wing coalition and a high point for the populist right. Often overlooked, the elections might also mark the fading of the German socialist party Die Linke into political irrelevance. Its demise teaches us valuable lessons for modern European politics

The September 2024 state elections in Germany mark a low point in public support for the governing left-wing coalition and a high point for the populist right. Often overlooked, the elections might also mark the fading of the German socialist party Die Linke into political irrelevance. Its demise teaches us valuable lessons for modern European politics.

Let me start with a personal anecdote that, I think, contains insights into how left-wing parties were able to maneuver themselves into such a disastrous position. Almost exactly one year ago I presented my research on representation gaps at a research conference in Berlin.

My main result was that all established German parties, from the center-right CDU to the far-left Linke, propose social/cultural policies that are much more liberal than what the average German voter or citizen prefers. Most notably, the average German demands much stricter immigration rules than any established party is ready to deliver. For more details, read here: I argued that this “representation gap” was responsible for the rise of the right-wing populist AfD and the corresponding decline of established parties.

By accident, there was a high-ranking member of the established socialist party Die Linke (“The Left”) in the audience.

After I had finished my presentation, this politician approached me, and we talked about the future of Die Linke. Like every single politician I ever met, she disagreed with my assessment and argued that people loved the political positions of her party. Instead, she saw the actual reason for the decline of Die Linke, which polled around 5% in federal elections at the time, in intra-party dissent.

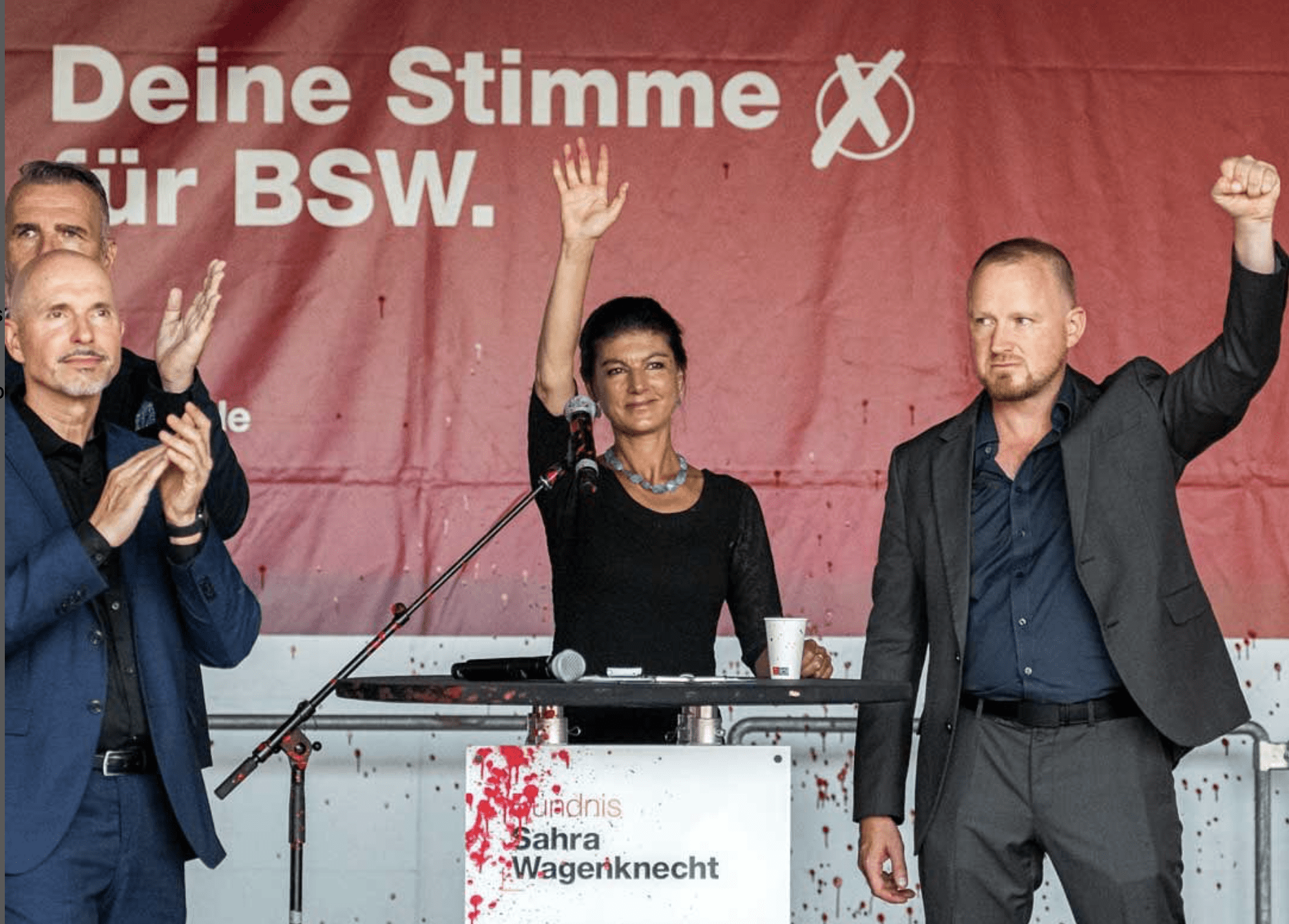

Indeed, a popular member of Die Linke, Sahra Wagenknecht, had split the party when she argued for it to take much more culturally conservative positions, particularly regarding immigration.

According to my theory, this was exactly the right approach to gain voters. In contrast, the Linke member I talked to argued that Wagenknecht was not the solution but the problem and that after her eventual departure from the main party, which was already foreseeable, Die Linke would rise again in the polls. I made the opposite prediction based on my theory.

If she left and formed a new party that copied the economic positions of Die Linke but combined that with more popular culturally conservative positions, this party would outdo Die Linke and attract many of their voters.

One month after we had made our predictions, Wagenknecht left Die Linke together with nine out of 38 former members of the Bundestag from Die Linke. Thus, around 26% of members of the Bundestag split from the party.

The new “Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht” (BSW) indeed combined left-wing policies similar to those of Die Linke with culturally conservative positions, most notably on immigration. In contrast, Die Linke doubled down on their culturally liberal positions. In particular, Die Linke nominated the controversial pro-asylum seeker activist Carola Rackete candidate for the 2024 European Parliament election.

Rackete became famous in her role as ship captain of the Sea-Watch 3. While her supporters claim that she was rescuing refugees abandoned in the Mediterranean, her opponents argue that she illegally transported migrants from the African coast to Europe. Independent of who is right in this argument, nominating Rackete was a clear signal in favor of asylum seekers.

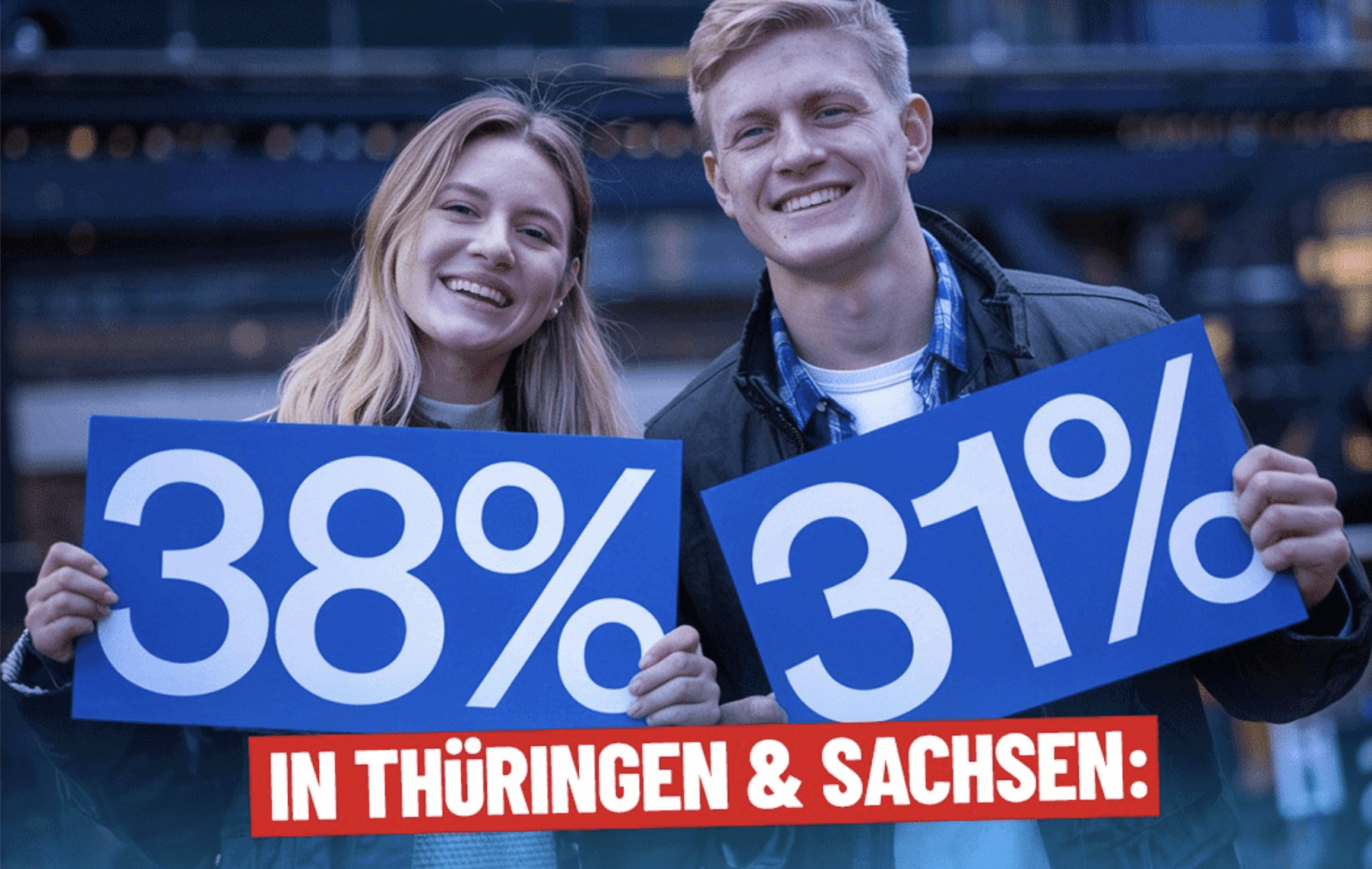

At the latest since the state elections in Thuringia and Saxony, it is clear which prediction was correct. Both states are historical strongholds of the left party. Thuringia specifically is the only state where the Left Party ever provided a state premier.

Yet, in the recent state elections, Die Linke got decimated. In Thuringia, it lost nearly 18 percentage points, from a vote share of 31% down to 13.1%. While it came out as the strongest party in the 2019 election, it is now only in 4th place, behind the nationalist AfD, the conservative CDU, and the new Wagenknecht party.

In Saxony, the party will not even enter parliament with an election result of 4.5% (down from 20.4 in 2019). The Wagenknecht party did much better in both states. It came in 3rd place in both, entering both parliaments with nearly 16% in Thuringia and just over 13% in Saxony.

These results are not confined to the two Eastern German states. In the recent European election, the Wagenknecht party reached 7%, doing much better than the Left party with 2.9% (down from 5.5% in 2019).

In current polls for the Bundestag elections, the Wagenknecht party (8%) is also well ahead of the Left Party (2.8%). According to these polls, Die Linke will likely be thrown out of the Bundestag in the 2025 federal elections while the Wagenknecht party will move in. If this happens, Die Linke will be subsumed in the “Other parties” categories when election results are discussed and can be considered an irrelevant party.

The Importance of Issue-Voting

However, I am already predicting that the left will be largely politically irrelevant from now on. In the eyes of most German citizens, the Wagenknecht party is a superior alternative to Die Linke due to its more conservative cultural policy position. Moreover, party membership of Die Linke is at its lowest level ever and continues to decline. This, together with Its weak election results and loss of representation in parliaments also means that its finances will deteriorate. Once trapped in such a vicious cycle, it is difficult to get out again.

What do we learn from this? First, politicians should not underestimate the power of issue-voting.

Most citizens vote primarily based on how well their policy attitudes are matched by the proposals of parties. Hence, I was able to predict the decline of Die Linke and the success of the Wagenknecht party purely based on their position in the policy space. Surprisingly many politicians seem not to be aware of this simple fact and give disproportional weight to other voting determinants like intra-party dissent or the charisma of the party leadership. These factors do matter too, but much less than policy positions of the party and much less than politicians think.

Second, representation gaps matter. Throughout Europe, nearly all established parties are culturally more liberal than the average voter. As long as this is the case, culturally conservative parties and right-wing populists in particular, are poised to rise.

Third, this episode is an example of a disconnect between the party elite and the voters of the parties. Among the party elite, most opposed Wagenknecht. But among voters, she was much more popular than the elite of Die Linke.

In this paper I show that this is no exception. Across Europe, party members are much more representative of the general population than candidates for parliament regarding political attitudes. This indicates that parties do not select a representative sample of their voters upward in the party hierarchy. Fixing this could help them in closing the cultural representation gap.

Throughout Europe, nearly all established parties are culturally more liberal than the average voter. As long as this is the case, culturally conservative parties and right-wing populists in particular, are poised to rise

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.