Why European Far-Right Parties Are Poised to Continue Rising

Europeans want policymaking that is culturally more conservative, for example, better protection of external borders and more priority on the wellbeing of European natives rather than third-country immigrants.

The two right-wing parliamentary groups, ECR and ID, are the big winners of the 2024 European Parliament election. Their combined vote share rose to 18.7%, causing commentators to label the new parliament as the most right-wing ever.

Under the impression of such events, it is easy to lose sight of underlying long-run trends. To fill this gap, this commentary takes a long-run perspective.

Few observers were surprised by the recent success of ECR and ID. During the last decades, a new type of party has established throughout Europe. Sometimes labeled right-wing populists, these parties distinguish themselves by particularly tough right-wing stances on cultural topics like immigration.

Right-wing populists have been increasingly successful in virtually all European countries for many years. The rises of Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Giorgia Meloni in Italy, and Geert Wilders in the Netherlands are just a few salient examples, and the 2024 EP election was in no way exceptional but followed this long-run trend.

Why are right-wing populists so successful?

To answer this question, one must understand how people vote. Evidence indicates that people mainly vote based on how close their personal policy attitudes are to the programs of parties.

In previous decades, the political space could be described well by a single policy dimension – the economic left-right dimension. Parties on the left were in favor of more redistribution and bigger states while parties on the right favored smaller states and less redistribution. More recently, however, issues like immigration and climate change have become increasingly important for voters.

People's attitudes on immigration and climate change are not notably correlated with their attitudes regarding redistribution or state intervention. At the same time, attitudes on these “cultural” issues strongly correlate with each other. Hence, cultural issues form a second dimension of the policy space, often labeled “the cultural dimension".

Established parties had much time to localize popular policy positions on the economic dimension. On cultural topics, they are much less experienced. It is therefore not surprising that the positions established parties take on cultural issues differ strongly and systematically from what the median voter wants.

As I show in this paper even Christian Democratic and “Conservative” parties are more liberal on issues like immigration than the average citizen or voter in their country. Consequently, about half of the European population views all established parties as too culturally liberal –there is a large representation gap on cultural issues.

Right-wing populists differ strongly regarding their economic positions. But they have all in common that they fill the cultural representation gap by offering culturally conservative policies. This is their secret to success.

The European Parliament is no exception. On cultural issues, the EPP is more liberal than the European median voter. Notably, many parties in the ECR, like Meloni’s Brothers of Italy are positioned quite close to the national mean voter. Hence, when focusing on the cultural dimension, the EPP is a center-left party group while the ECR is center-right.

Recent research shows that right-wing populists rise because voters find cultural topics like immigration increasingly important. The more these topics matter, the more do the positions of parties on these issues matter. This benefits right-wing populists because their cultural positions are particularly popular among citizens.

Topics like immigration will continue to increase in importance because immigration pressure will increase due to high birth rates around Europe. Hence, the rise of right-wing populists will most likely continue until the cultural representation gap is closed. Since right-wing populists often represent the more conservative 50% of citizens, they have the potential to unite about half of all votes in the long run.

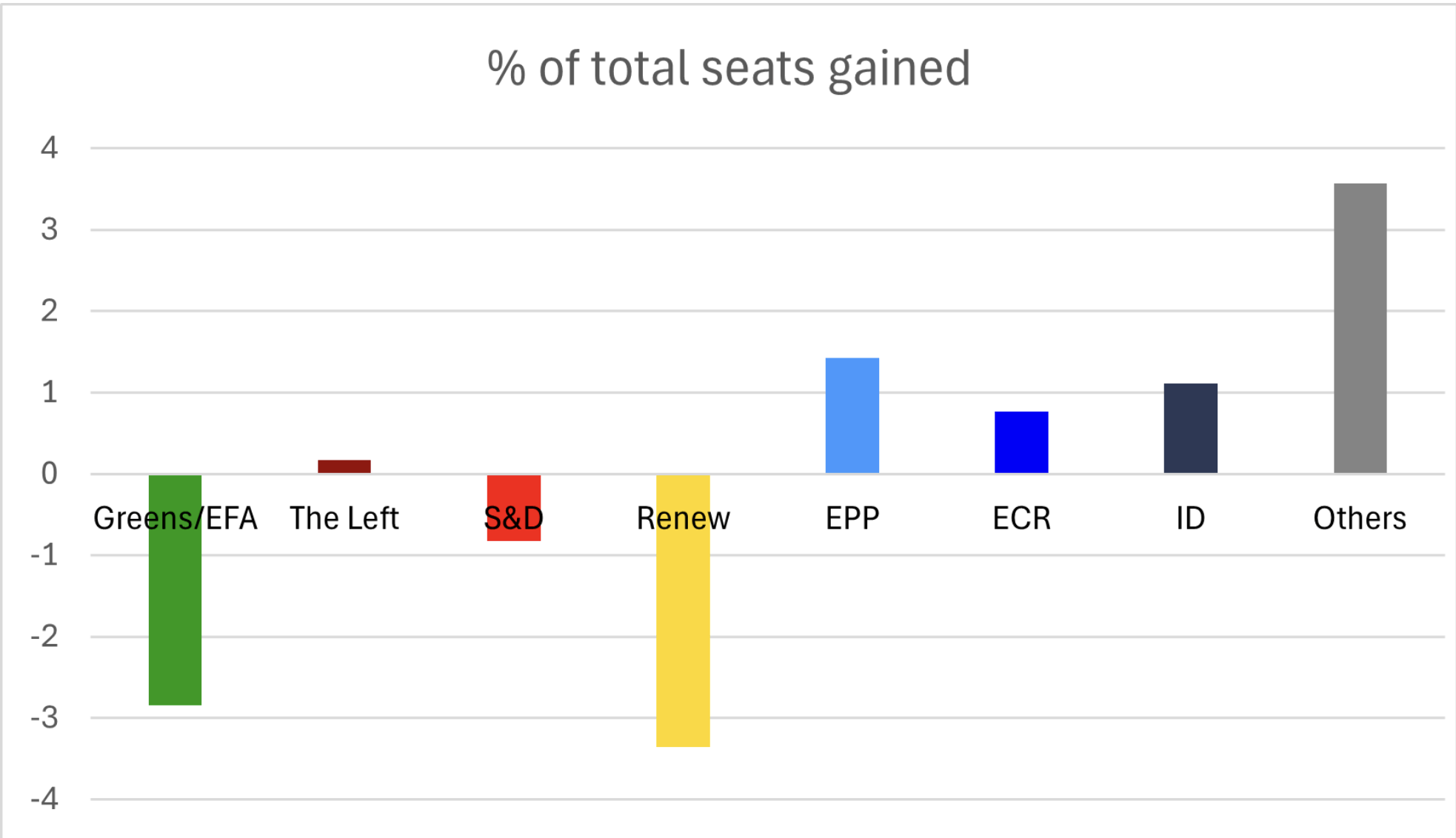

Figure 1: Seats Gained and Lost by Political Group

Note: This figure shows for each EPP group how much percent of all seats it gained through the 2024 election.

Figure 1 displays seat gains in percent for all groups in the European Parliament. For instance, the Greens held 10.1% of all seats in the 2019-2024 Parliament (after Brexit) while they now hold only 7.2%. Hence, they lost nearly 3 percentage points.

The figure orders all groups according to their cultural position, from very liberal on the left to very conservative on the right. “Others” are located on the far right because this group contains many parties, like the AfD, that were expelled from right-wing groups for being too extreme.

Viewing the election through the lens of the cultural dimension reveals a clear pattern. Even though the correlation is not one-to-one, being more conservative is strongly associated with gaining more seats. Combined, culturally liberal groups lost heavily while all conservative groups rose.

The message to MEPs could not be clearer: Europeans want policymaking that is culturally more conservative, for example, better protection of external borders and more priority on the wellbeing of European natives rather than third-country immigrants.

Now that cultural topics become increasingly important, voters will ultimately ensure that all parliaments reflect their cultural attitudes. The median voter holds cultural attitudes between EPP and ECR and attitudes on cultural issues are quite stable over time. Hence the EP will see populists rising until the median MEP holds attitudes between what are now EPP and ECR.

Leading politicians are increasingly aware of this and converge toward a cultural position that combines elements of right-wing populists and conservative mainstream parties. For instance, Meloni has become less radical regarding immigration and adopted several near-mainstream positions on other topics while mainstream politicians like Mette Fredriksen in Denmark, Emmanuel Macron in France, or Friederich Merz in Germany have moved closer to right-wing populists on immigration.

This way, a new consensus on cultural policy will emerge. This consensus will include policy positions that fill the cultural representation gaps. Most notably, it will include much more priority given to the wishes of Europeans vis a vis non-Europeans but also a pro-EU stance and climate protection.

If you are interested in the European Parliament activity, please check a new tool that the IEP@BU has just launched, with professors Simon Hix and Abdel Noury: the EPVM - European Parliament Vote Monitor

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.