Why Subsidising Exporters Means Bankrolling Trump’s Tax Cuts

Propping up EU firms hit by US tariffs with public funds risks taxing Europeans to subsidise American consumption and federal revenues. A commentary by Marcello Messori

The European Union’s (EU’s) capitulation to US President Donald Trump’s command of tariffs on “reciprocal” trade will have consequences that go far beyond the immediate hit to exports of European member states. The commitments made by the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, on the European exorbitant purchases of US energy and defence systems over the next few years offer important examples in this respect.

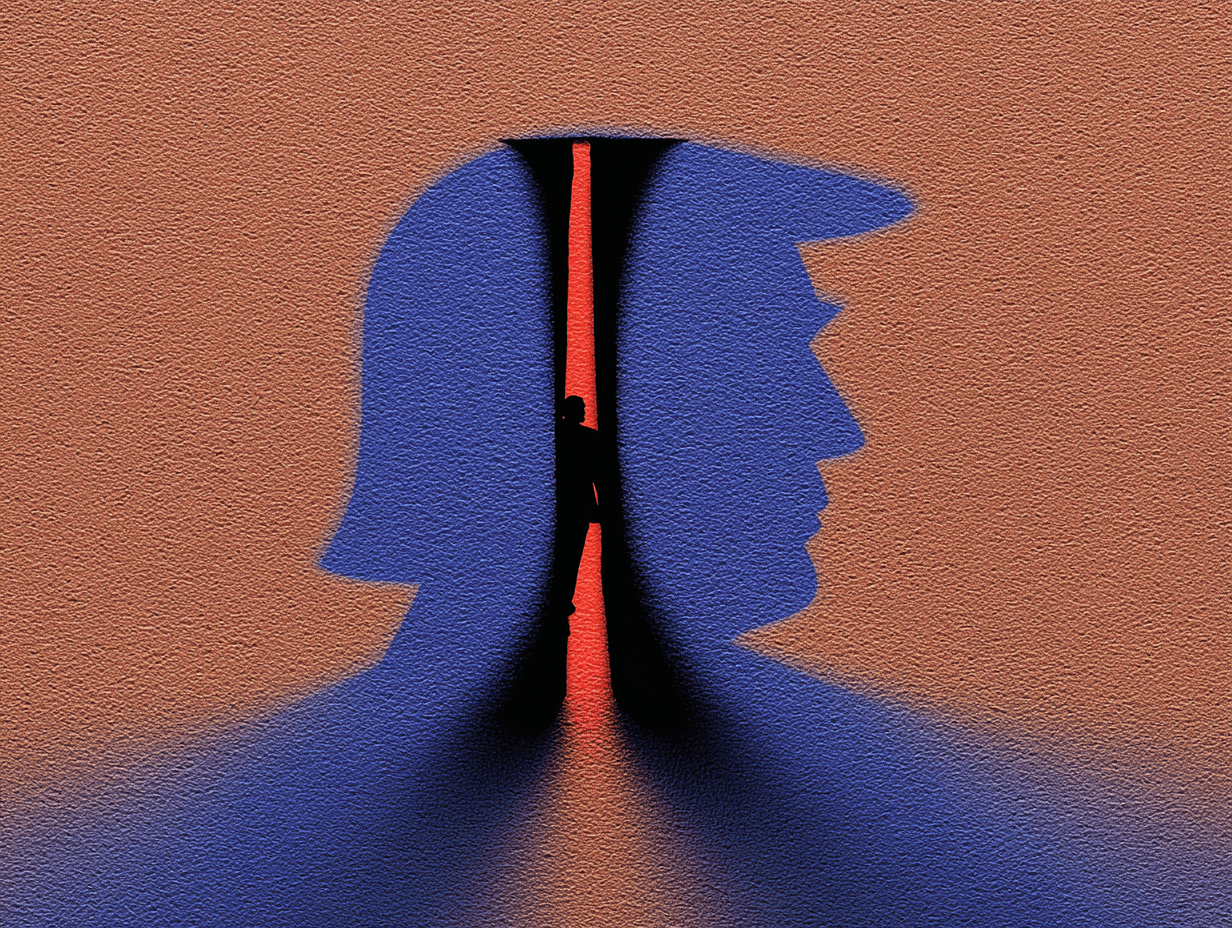

There is, however, an even more insidious and long-lasting risk that could affect European economic policy: the decision of the EU institutions or various countries to subsidise the exporters targeted by US tariffs. Such a move would amount to increasing tax pressure on European citizens to support both the revenues of the US federal budget and the US consumption, as well as counteracting the US inflation trend. The logic is indirect, but clear.

Public support for European producers would aim to limit the price increases on goods and services that face new tariffs and are supplied in the US market. Hence, this support could cushion the drop in sales and, if public subsidies were well-calibrated to price elasticity, even increase the total value of European exports to the United States. At first glance, both European producers and US consumers and investors would be better off: exporters would protect their market share, while purchasers would face more moderate increases in the prices of their imports.

Yet a significant portion of the monetary proceeds from the sales of European firms on the US market would not remain with these firms but would be collected by the Trump administration as tariffs, and it would thus help to offset some of the decrease in public revenues due to tax cuts introduced by the so-called “Big Beautiful Bill”. In addition, President Trump would secure two additional political wins: the inflationary impact of his tariff policy would be blunted, and US importers—his potential voters—would experience a more limited erosion in their purchasing power.

The economic logic of this sequence of events is plain. By subsidising their own exporters, the EU or its member states would boost US aggregate demand and helping President Trump to reduce the US federal deficit. Such transfers from the EU to the United States would have direct budgetary consequences at either the EU level or the national level. Given that several member states are opposed to even very modest increases in the ‘real’ size of the next EU multiannual financial framework, and given binding constraints on imbalances in national budgets, there is negligible room to finance such “gifts” to Trump through further increases in public deficit and debt. Hence, the only alternatives would be either higher taxes to increase public revenues or spending cuts in other public interventions (such as social expenditures). In short, the EU’s response to the US excessive tariffs would be to support Trump’s policy agenda, turning the US tax cuts into higher taxation or fewer social services for European citizens: first the injury, then the insult.

This is not to say the EU should passively adapt itself to the “Scottish tragedy” that occurred on Trump’s golf courses, and expose the European productive system to its current political and institutional fragility. Conversely, the EU should strengthen its Multiannual Financial Framework and improve the reallocation of central expenditures already designed in the initial proposal of the Commission. The economic strategy to be pursued is straightforward. If the EU institutions aim at helping the European production system, they must support research and innovative investment as well as mobilise the significant amount of financial wealth for the green and digital transitions. These steps are crucial to reshape the production model of the area, which is stuck in the trap of mature technologies.

As one of the world’s strongest economies, the EU can no longer base its growth on net exports alone. To close its technological gap towards the United States and China and to weave a multilateral alternative to Trump’s world of bilateral conflicts, the EU must leverage its strength points in manufacturing and reduce its weaknesses in advanced services. This means to focus the EU’s limited resources on a centralised industrial policy that makes the single market truly effective and fosters excellence, and that is compatible with the European social model based on low environmental impact, effective regulation, and a strong welfare state.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.