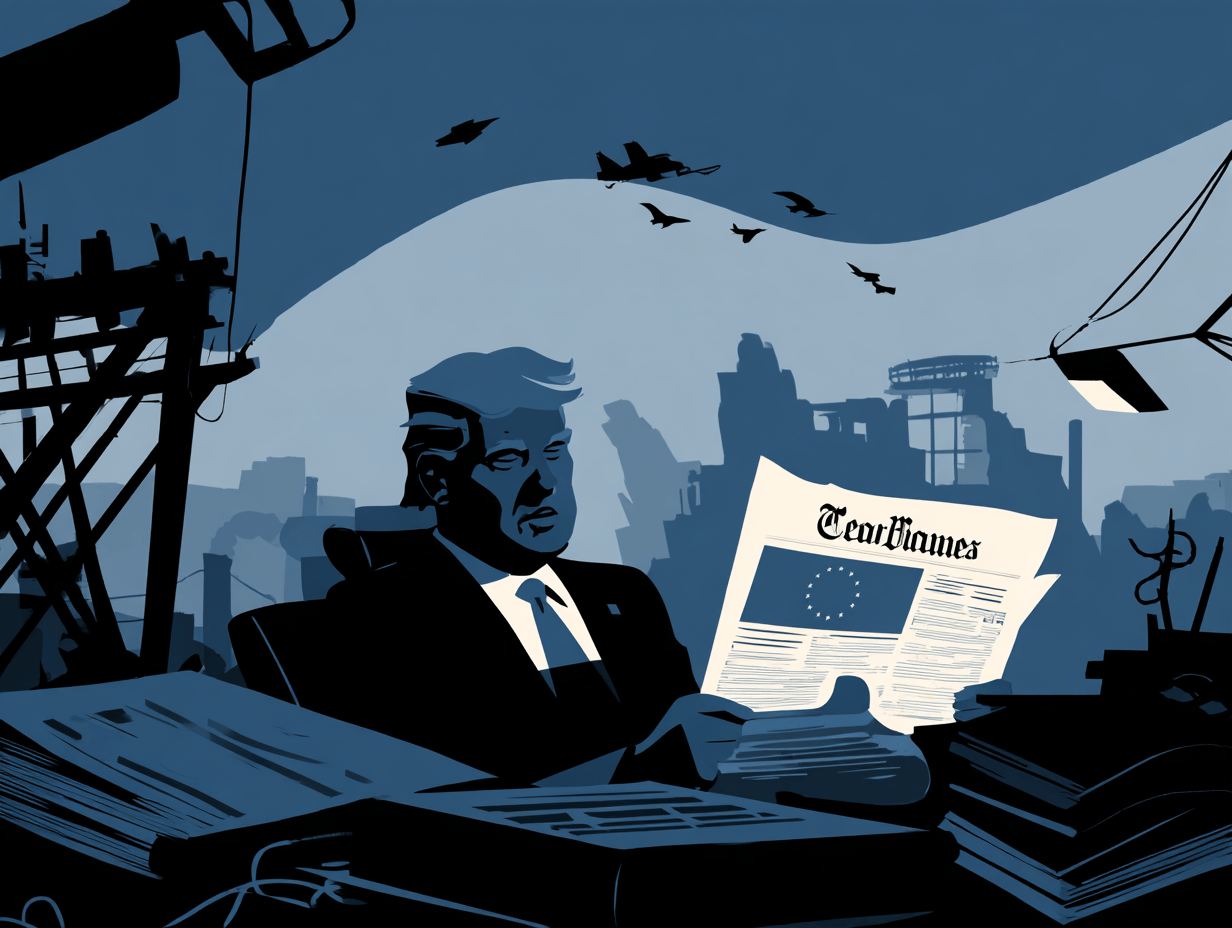

How Europe Anticipated the Trump Shock — and Still Came Up Short

The EU entered 2025 fully aware of the geopolitical and economic challenges ahead. Its failure to act has left the Union exposed, fragmented, and increasingly constrained by US power. A commentary by Marco Buti, and Marcello Messori

At the start of this year, the persistence of geopolitical conflicts, the election pledges of newly elected US President Donald Trump, and the European Union’s longstanding economic and institutional weaknesses made the challenges of the next twelve months abundantly clear.

The EU needed to prepare credible responses to Trump’s threats; establish a genuine common defence policy backed by meaningful resources; expand its budget; overcome the fragmentation of its financial markets to start closing its widening technological gap; safeguard its comparative advantages, particularly in the green transition; and counter negative demographic trends through active labour-market policies and immigrant integration.

By the end of 2025, however, the EU risks finding itself in a dead end.

Shielding themselves behind the principle of national competence, member states refused to finance higher defence spending through common debt. Instead, they allocated €150bn in loans to individual member states to support nationally designed — if jointly endorsed — defence projects.

Countries were also granted the option to exclude, for four years, increases in national defence spending of up to 1.5 per cent of GDP from the fiscal rules’ relevant calculations.

Because these initiatives lacked adequate central coordination, they proved insufficient for any gradual emancipation of the EU from US military protection.

As a result, and in order not to jeopardise American commitment to NATO, the EU has bowed to Washington’s demands — including the imposition of tariffs on European exports to the US market.

Should similar retreats extend to the regulatory framework governing digital services within the Single Market, the EU would in practice become an economic and political vassal of the United States.

Even the progress achieved in trade agreements with the rest of the world would fall far short of substantiating Europe’s ambition of “strategic autonomy”.

These trends coincide with a widening — not narrowing — gap between Europe’s productive system and the technological frontier, where intensifying US–China tensions impose increasingly binding constraints on EU growth.

The Union remains hampered by a relatively small advanced-services sector, by manufacturing technologies that are too “mature”, by widespread rent-seeking among small and micro-enterprises, and by the inefficient allocation of its vast financial wealth.

Against this backdrop, the Commission’s otherwise sensible proposal to increase funding for research and innovation in the next Multiannual Financial Framework is too modest to reverse the negative momentum.

Moreover, reactions from other European institutions — starting with the European Parliament — seem aimed at minimising budget reallocations toward European public goods and avoiding increases in centralised spending for common projects.

The result is that member states continue to rely on net exports to global markets that are increasingly unstable and governed by raw power dynamics — hoping that tariffs and other barriers will not have negative medium- or long-term effects, or that they will simply vanish.

This late-mercantilist illusion has pushed the EU to impose a sharp slowdown on the green transition and to replace the financing mechanisms for EU-level industrial policy — as proposed in the Draghi report — with looser state-aid rules for individual countries.

The consequence has been a proliferation of nationally confined initiatives that, by definition, cannot generate efficient and innovative investment at scale.

In the second half of 2025, faced with a lack of resources for a central industrial policy, the new mantra of EU institutions has been to attribute Europe’s deepening technological lag and sluggish growth to excessive regulatory burdens — framing sweeping “Omnibus” simplification packages as the way out.

Three risks follow.

First, regulatory uncertainty now adds to geopolitical uncertainty, further discouraging investment.

Second, by overstating the faults of regulation, the probability increases that simplification becomes a gateway to “anything goes”, ultimately benefiting Chinese and US competitors.

Third, as shown by recent steps backward on constraints for monopolistic AI service providers, deregulation worsens the EU’s vulnerability to Trump’s power plays.

Yet the Union is not condemned to inevitable decline.

A version of this article originally appeared in Il Sole 24 Ore

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.