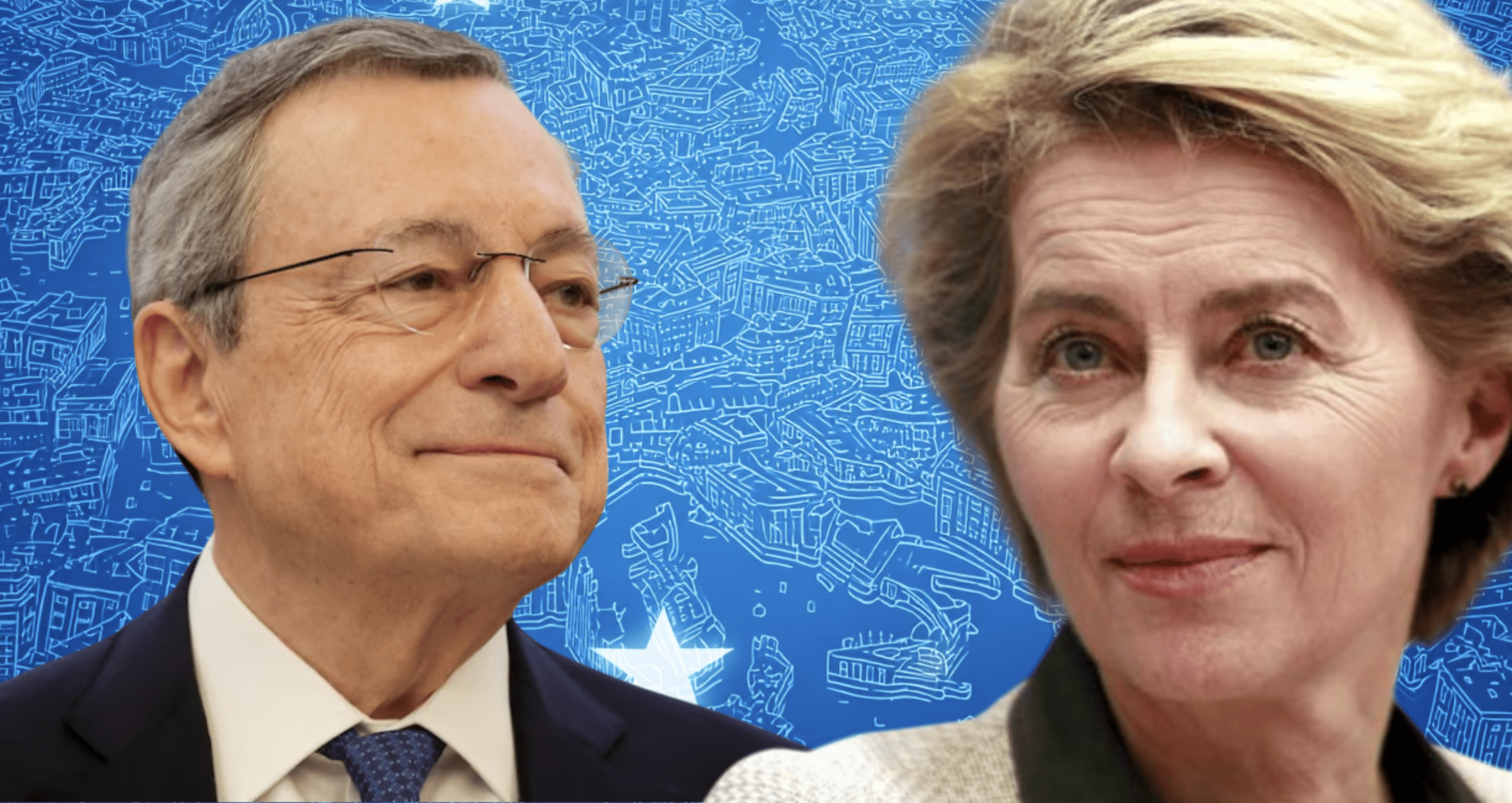

How Ursula von der Leyen Sidelined Draghi’s Competitiveness Agenda

One year on, the European Commission has applauded Mario Draghi’s proposals — but failed to apply them. A commentary by Marco Buti, and Marcello Messori

Next Wednesday, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen will deliver a difficult State of the Union address to the European Parliament. Beyond justifying her approach to tariffs and reaffirming Europe’s commitment to Ukraine, she will have to account for how the Commission has followed up on Mario Draghi’s report on European competitiveness, published a year ago.

That report aimed to reform the EU’s production model to close the widening technology gap with the United States and China, and to reaffirm Europe’s relevance in a shifting and threatening geopolitical landscape.

Starting from the EU’s stark weaknesses, it laid out an economic policy agenda designed to revitalise the single market and to underpin the bloc’s strategic autonomy — avoiding a slow but inexorable decline of Europe’s social model.

Much criticism focused on the report’s estimate of the funding needed: €750bn–€800bn annually over six years to deliver the necessary innovation investments. But as international tensions rise and Europe’s fragilities are further exposed by the US President Donald Trump’s actions, another question looms larger: whether EU and national authorities are capable of conceiving such ambitious strategies.

At the report’s launch, von der Leyen promised to embed its agenda into the programme of the Commission she sought to lead again. Today, in her second term, the question is: how much of Draghi’s agenda has actually been realised?

The answer depends on whether one looks at narrative, broad policy direction, or specific flagship measures.

On the narrative front, EU institutions have been almost enthusiastic. Every Commission communication has invoked Draghi’s report, ritualistically paying tribute to competitiveness, simplification, completion of the single market (especially in finance) and support for innovation.

Yet beyond omnibus packages — where the line between simplification and deregulation blurred — the rich catalogue of proposals has not translated into concrete financing or implementation.

For instance, principles of competition and non-fragmentation in financial markets have not pushed the Commission to dismantle national distortions that block banking consolidation.

Results have been even more disappointing for flagship measures that required crossing “red lines.” Germany and Nordic countries opposed risk sharing, while Italy and others refused to cede sovereignty. Together, they prevented centralised financing and production of European public goods.

The draft EU multiannual budget for 2028–34 confirms this failure. Increases in spending on competitiveness, research, and external action are not backed by common borrowing. With the budget fixed at just 1.1 per cent of EU GDP (after NextGenerationEU repayments), it is unrealistic to expect an industrial policy capable of transforming Europe’s mature and lagging production model. The fallback is to loosen national state aid rules.

But in responding bilaterally to Trump’s protectionist moves, Europe risks undermining the integrity of the single market — also stressed in Enrico Letta’s report of April 2024.

The nationalism dominating most member states exposes the gap between the “economic necessities,” which would require more Europe, and the “political feasibility,” which blocks such evolution.

Faced with this diagnosis, two paths remain open.

First, a “dynamic maintenance of the pipes,” focusing on those Draghi proposals that face fewer political and ideological obstacles. For example, the Commission’s recent plan to reduce fragmentation in EU financial markets by relaunching securitisation aimed at financing SME groupings with higher technological content and risk appetite.

Second, cross-border projects in technological innovation and artificial intelligence — consistent with the green transition and highlighted in the Draghi report — could be pursued by coalitions of willing countries, combining national and EU resources.

Looking ahead, the priority is to create more favourable political conditions for truly European progress. Draghi’s report privileged “innovative” European public goods over “solidaristic” ones. A more balanced mix between the two would soften national resistance, by aligning investment with Europe’s social model and striking a fairer balance between efficiency and equity.

A version of this article appeared in Italian in Il Sole 24 Ore.

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.