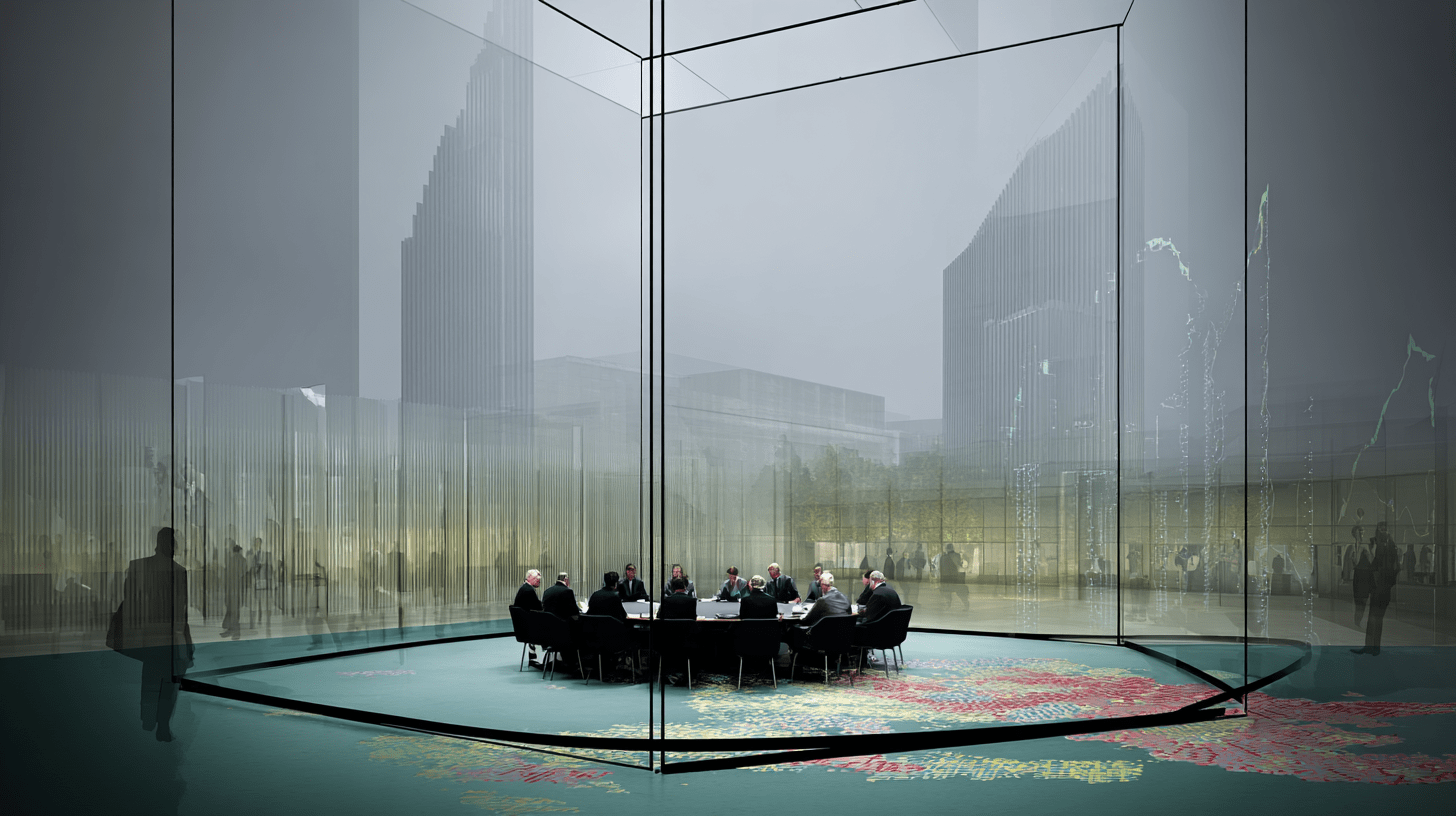

A halved European Council

Four years after Versailles set out a shared agenda, leaders are still dodging the hard question of how to fund common European public goods. A commentary by Marco Buti, and Marcello Messori.

Just under four years ago, at the urging of France’s rotating presidency, EU leaders gathered for an informal European Council amid the gilded rooms of Versailles. Even as Russia’s aggression against Ukraine cast a leaden shadow, the first part of that summit raised expectations.

President Emmanuel Macron had sketched an ambitious format: devote the opening day to selecting shared objectives — the “what” — and the second day to defining the instruments to deliver them — the “how”.

The first-day agreement was encouraging.

Leaders converged on European ends: strengthening defence capabilities, reducing energy dependence, building a more innovative economic base, and relaunching public and private investment fit for purpose.

The second step, however, remained unfinished. The consensus on goals did not translate into agreement on tools that would build a central fiscal capacity.

February 12 informal meeting made no more progress than Versailles. After four years, the objectives are largely unchanged — an indictment of the inadequate advances in Europe’s construction during a phase of radical change.

Moreover, the Belgian summit did not even raise the opportunity to discuss instruments, deferring everything to the March European Council, traditionally devoted to economic issues.

The choice to convene a European Council that was, in effect, “halved” compared with Versailles may not have been accidental.

The Italian-German non-paper of January 23, taken as the meeting’s reference text, set out defensible objectives but proposed instruments that sit uneasily with those objectives.

As Mario Monti has noted, strengthening the single market is incompatible with loosening state-aid rules amid a broader deregulatory thrust.

Weakening common rules while expanding state aid increases divergences among countries and eases the construction of national barriers.

As we argued in our January 24 intervention in HuffPost, this contradiction points to the need to overcome it through centralised financing for the production of European public goods.

In the revised version of that non-paper, now also signed by Belgium, the reference to state aid has disappeared — without being replaced by common instruments — and deregulation has been elevated to an objective in its own right. The result is a neglect of a basic fact: defining goals must be completed by defining effective tools.

Worse, the contradiction has been shifted onto the level of objectives, by denying that the single market should be strengthened through regulation that prevents individual member states from increasing fragmentation.

Within the framework outlined by many of the Commission’s “Omnibus” packages — and echoed by the three-signature document — the risk is high that cases such as Italy’s beach-concession saga or Germany’s “authorisations by fax”, cited by Ursula von der Leyen in the European Parliament, become systemic.

In this sense, like Viscount Medardo of Terralba — the protagonist of Italo Calvino’s The Cloven Viscount — yesterday’s European Council can look hollow beneath a cloak inflated by the wind of declarations, yet it produced a distinctly “bad” result: an exclusive commitment to deregulation (and therefore, implicitly, to allowing explicit or hidden state aid), accompanied by insistent but generic calls to devise instruments for goals not unlike those invoked, without success, at Versailles.

To continue Calvino’s metaphor, yesterday’s meeting also illuminates the missing half that should have corresponded to the unexpected arrival of Medardo’s “good” part: building a central fiscal capacity to finance European public goods.

The single market requires the EU to develop common projects that innovate the productive structure, reduce dependence in defence, safeguard the social model and environmental attention. Without these essential ingredients, Europe’s strategic autonomy will remain out of reach.

The lesson Europe should draw — after having averted, perhaps only temporarily, a US “aggression” over Greenland — cannot be reduced to a sigh of relief and renewed flattery towards Donald Trump.

The world order has changed for good and, under the current US administration, sighs of relief are quickly destined to turn into gasps.

Yet agreement on the “good half” is still missing.

Faced with French insistence, German chancellor Friedrich Merz has declared his aversion to adopting common debt instruments, even if Germany’s debate on a European safe asset is not closed.

Giorgia Meloni, for her part, has tried to split the viscount’s “good” half in two: sharing European debt, but to finance national projects rather than European public goods.

Calvino’s message is that building effective, realistic instruments should not separate the parts; it requires the two halves of Medardo to reunite.

A gradual construction of a European industrial policy — centred on centralised debt to produce European public goods that close gaps with the technological frontier and strengthen social cohesion — should catalyse larger flows of innovative private investment.

Those flows, in turn, must be financed by mobilising the private wealth of households and firms through efficient intermediaries within unified European financial markets.

In that perspective, simplifying the EU’s regulatory framework — making regulation more effective and efficient — would be a positive component.

A tight timetable (a roadmap to be defined by March to complete the single market by 2028) must be paired with a battery of measures and the related financing, starting with defence.

The reality, however, is that common debt remains divisive. In the past, informal Councils have nonetheless created the conditions to cross “red lines” precisely because of their informal nature.

The pro-common-debt position taken by the European Central Bank — and, above all, by the president of the Bundesbank, Joachim Nagel — opens the possibility of a productive debate in Germany as well.

We hope that, in March, Europe is not left with only the will-o’-the-wisps Calvino evokes at the close of The Cloven Viscount.

A previous version of this article was published by the Italian daily HuffPost

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.