Why Incremental Reform May be the EU’s Only Way Forward

Between geopolitical shocks, technological rivalry and domestic identity politics, the EU needs a strategy of pragmatic retooling to preserve competitiveness, democracy and social inclusion. A commentary by Marci Buti, and Marcello Messori

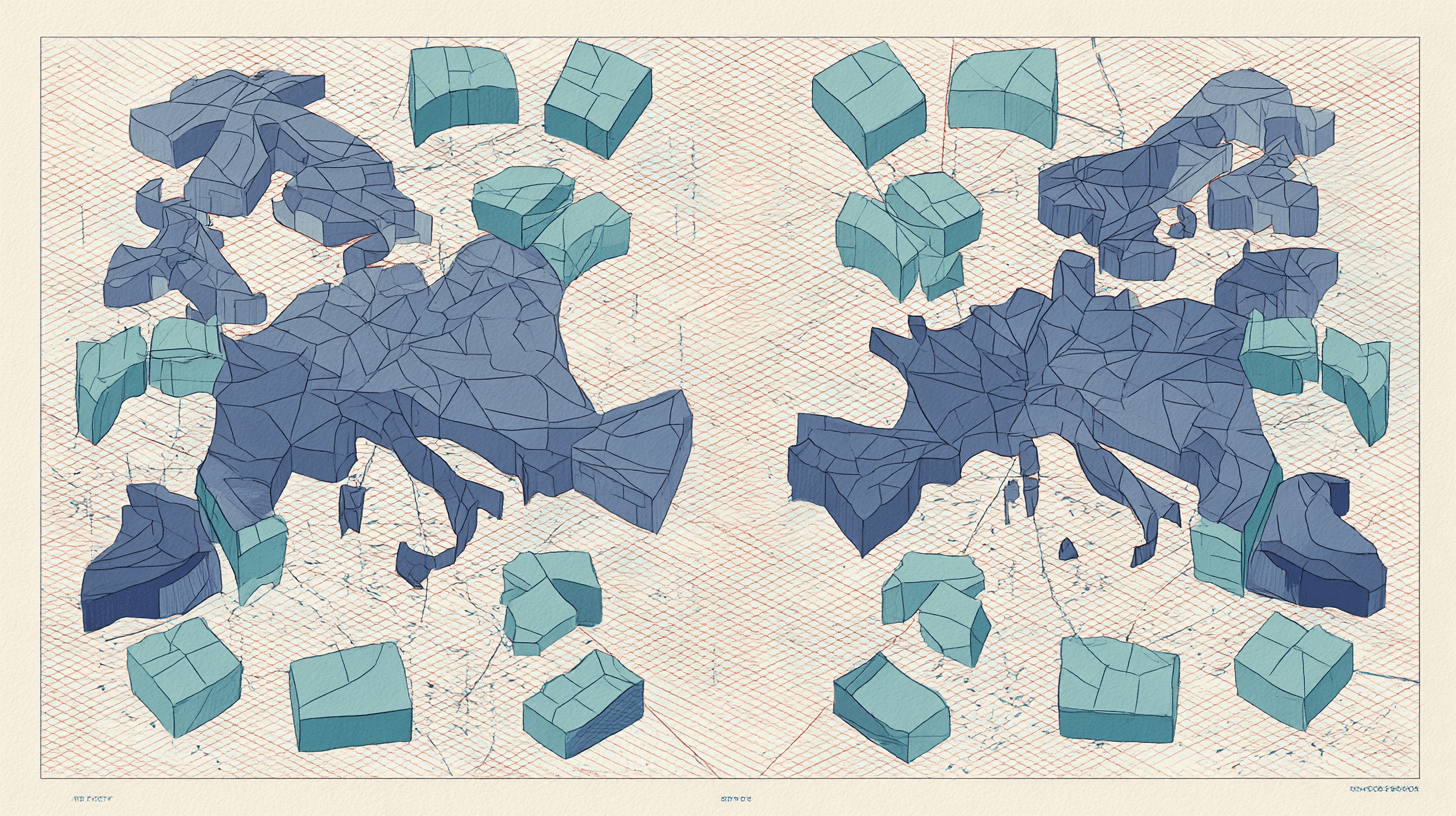

The European Union stands today at a crossroads, suspended between the urgency of structural transformation and the paralysis imposed by national identity politics.

Geopolitical challenges — crystallised in wars on Europe’s borders and in an increasingly fierce technological contest between the United States and China — have eroded the EU’s long-standing comparative advantages, built on soft power and the rule of law.

In a world in which Donald Trump replaces an imperfect multilateralism with bilateral power conflicts, and China asserts dominance over strategic inputs and outputs, Europe’s economic model — based on mature technologies and a dense network of small firms — risks obsolescence.

The EU’s recent trade agreements matter, but they are not sufficient to address this problem.

The informal European Council meeting scheduled for 12 February, almost two years after the Letta and Draghi reports, should be fully aware of the scale of this challenge and take decisions that secure a future for Europe’s oasis of democracy and social inclusion.

To escape the trap of mature technologies, the EU’s internal agenda must complete the single market, including full integration of financial markets, and create a central fiscal capacity backed by a European safe asset.

The resulting financing of so-called European public goods would form the pillars of a common industrial policy, capable of supporting public and private investment in innovation and the green transition. It can be shown — through cost-benefit analysis — that well-calibrated packages of European public goods create an environment conducive to innovation and social protection, delivering benefits to every member state.

Yet the EU’s current political-institutional reality is moving in the opposite direction. Many governments prefer to fight for looser constraints on state aid, in order to stimulate national investments that fall short of minimum efficient scale and fragment, rather than strengthen, the single market.

This divergence between economic necessity and political feasibility is driven by the “identity politics” prevailing in many EU countries.

Anxiety over the loss of social status — stemming from income and wealth polarisation, technological change, and migration flows perceived as threats rather than opportunities — has pushed growing segments of the population towards conservative and nationalist preferences.

European and national institutions have failed to provide convincing responses. As a result, the transfer of sovereignty to the EU, required to transform Europe’s economic model, is no longer seen as a positive necessity but as an aggravation of looming threats.

The outcome is a “trilemma of political integration”: it is impossible to guarantee simultaneously the primacy of the nation state, economic competitiveness and a system of common financing. At the same time, a full federal leap is not currently achievable.

As we argue in a forthcoming essay, a way out lies in a strategy of “active maintenance” — retooling.

This means setting aside, in the short term, grand comprehensive reform designs and focusing instead on targeted interventions that do not require large transfers of national sovereignty, but that generate measurable efficiency gains with positive spillovers across the EU’s already deep and entrenched interconnections.

By acting on specific nodes within these interconnections, the system’s functioning can be gradually improved.

The criteria for selecting the most promising maintenance interventions are their externalities — the ability to generate positive effects beyond the immediate area of action — and their capacity to trigger turning points, through the accumulation of improvements that feed back into citizens’ political preferences.

Concrete examples include the development of securitisation instruments to support small firms; a “railway silk road” linking EU capitals through high-speed rail; and a Europeanisation of state aid so that it supports European, not merely national, investment.

In parallel, the use of EU directives should be curtailed in favour of EU regulations, which reduce national distortions and facilitate a level playing field across markets.

A gradual approach, based on localised but interconnected steps, could ease current political constraints and prepare the ground for broader consensus, eventually leading to the “pragmatic federalism” advocated by Draghi.

Rather than issuing proclamations about Europe’s common destiny or announcing disruptive but vague objectives destined for the cupboard of the EU’s “lost projects”, European leaders meeting on 12 February should aim to achieve three concrete outcomes: approve a focused but meaningful list of actions, ensuring that internal and external agendas move in parallel; define the budgetary instruments, regulatory steps and governance initiatives needed to implement them; and agree on a tight timetable for their full execution.

A previous version of this article was published by the Italian daily Il Sole 24 Ore

IEP@BU does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.